GREECE

History

History

Cities in GREECE

| Athens |

Popular destinations GREECE

| Aegina | Alonissos | Andros |

| Chios | Corfu | Crete |

| Hydra | Kalymnos | Karpathos |

| Kefalonia | Kos | Lefkas |

| Lesbos | Mykonos | Naxos |

| Paros | Patmos | Peloponnese |

| Poros | Rhodes | Samos |

| Santorini | Skiathos | Skopelos |

| Spetses | Thasos | Zakynthos |

History

Prehistory and Bronze Age

The Grave Circle A, and the entrance of the citadel (left), at Mycenae, GreecePhoto: Andreas Trepte CC 2.5 Generic no changes made

The Grave Circle A, and the entrance of the citadel (left), at Mycenae, GreecePhoto: Andreas Trepte CC 2.5 Generic no changes made

As far back as the Paleolithic, the Old Stone Age, Greece was populated by people who made a living from hunting and gathering fruits. From around 8000-7000 BC. agriculture and animal domestication was transferred from the Middle East to Greece.

The most important finds from the Neolithic era (ca. 6000-3000 BC) come from the region of Thessaly, especially from the settlement of Sésklo. What is special is that they have found an octagonal house here. Until then, mainly round houses were built. The hand-formed ceramics found here can also be found in other Greek regions.

With the Bronze Age (ca. 3000 BC) the Helladic culture begins on the Greek mainland. The bronze was imported from Asia Minor and is now found in various places. Around 1900 BC. The formation of the Greek people gets off to a good start when various Indo-European speaking tribes spread all over the Greek territory. Well-known names such as Olympia, Mycenae and Tiryns are among the sites. These immigrants brought with them the oldest phase of the Greek language and other cultural elements that would later become so well known, such as the sky god Zeus.

These peoples were also strongly influenced by the Minoan culture which was causing a furore in Crete at that time. The combination of these two cultures led to a high point in Mycenaean culture in the late Helladic era. The dominance of Mycenaean culture on the mainland was far from constituting political unity; probably at the head of each district was a priest-king who was at the top of a palace bureaucracy.

During this period, the Cyclades archipelago developed between Crete and the Greek mainland as a starting point for the trade connections that were established in both the east and the west.

The dark ages (c. 1200–800 BC)

Ancient Greek pair of terracotta bootsPhoto: Sharon Mollerus CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Ancient Greek pair of terracotta bootsPhoto: Sharon Mollerus CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Among other things due to the large population movements around 1200 BC. Mycenaean culture had collapsed and the Iron Age began in Greece and the formation of the ancient Greek people was completed. There was a cultural decline and not much is known about the historical developments during this time, hence the term "dark ages". At the end of this era, the world famous epic of Homer, Iliad & Odyssey, was created.

During this period the Dorians invaded Greece and the Ionians migrated to the islands of the Aegean Sea and the coast of Asia Minor. Just like on Crete, the typical Greek form of government, the polis, arose there. This form of government would also be introduced fairly quickly on the Greek mainland. The polis was an aristocratic form of government that relied on large land ownership or what had to pass for it. The nobility did face competition from a class that had made a fortune in trade.

It was also during this time that the alphabetic script was created, more or less taken over from the navigators of the Phoenicians. The social environment was still dominated by the "phyle", the old tribal connections, which date back to the Helladic period.

The colonization era (ca.800 / 750–600 BC)

Ruins of Sparta, GreecePhoto: David Holt CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Ruins of Sparta, GreecePhoto: David Holt CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

During this period a lot changed, including the monarchy, except in Sparta. Trade (the rise of coins) became increasingly important and a form of industry also emerged. The middle class became a new class and would become the core of the army. As a result, people also started to make political demands.

Nevertheless, industry and trade did not develop fast enough and food shortages arose due to the poor soil and this led to overpopulation and great tensions in political and social areas. This created an enormous colonization movement in which the Greeks settled on almost all coasts of the Mediterranean. The rise of Persia, Carthage and Etruria put an end to these movements. Politically and militarily, Sparta developed into the most powerful state and in the cultural field, Ionia predominated.

The sixth century BC.

Stadium Olympia, GreecePhoto: Drno CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Stadium Olympia, GreecePhoto: Drno CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Due to social and political tensions, most states were led by a "tyrannos", powerful men of the aristocracy who, with popular support, took over supremacy. Only Sparta, which had united almost all of the Peloponnese in a military league, managed to escape this.

In this century, Athens also became increasingly popular. In the colonization era, the whole of Attica had already united into one big polis and there was therefore no need to participate in the colonization. Solon, who also drafted a large number of laws, tried to solve the economic problems by stimulating trade and industry, but hardly succeeded. As a result, social tensions also arose in Athens and the arrival of a tyrant was inevitable (Pisistratus). In the cultural field, Athens also took the lead and Ionia and the Greek areas in the west, Sicily and southern Italy, remained important.

This was also the heyday of the Olympic and Pythian games in connection with the worship of communal gods. Clisthenes founded at the end of the 5th century BC. democracy in Athens.

The fifth century BC.

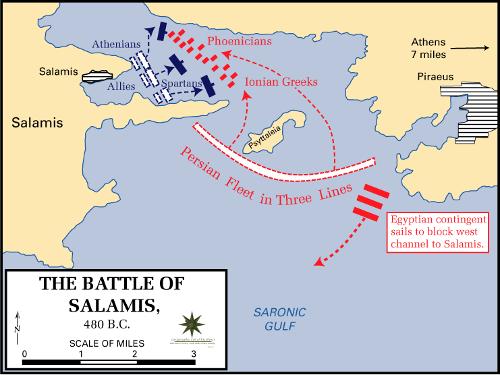

Battle of Salamis, GreecePhoto: Public domain

Battle of Salamis, GreecePhoto: Public domain

In 500 BC. In Asia Minor a revolt broke out by the Ionians aided by Athens against King Darius' Persian Empire. Darius then sent a punitive expedition to Athens which, however, failed completely at Marathon in 490 BC. This is where the Greco-Persian Wars started, the great battle between East and West. In 480-479 BC. Xerxes, the son of Darius, lost the important battles at Salamis and Plataeae and freedom was saved, among other things, by the exemplary cooperation between Athens and Sparta.

Both Athens and Sparta claimed victory, causing the rivalry between the two cities to return to dangerous proportions. In 431 BC. that tension eventually culminated in a war that divided the entire Greek world. In the second half of the war from 413 to 404 BC. Sparta won the battle with the help of the Persians. However, Athens and Sparta had been so weakened by the war that Thebes plunged into a power vacuum and in 371 BC. even defeated Sparta, considered invincible, on its own soil. The rule was short-lived because the Macedonian Empire was expanding during this time.

The fourth century BC.

Statue of Alexander the Great, Thessaloniki GreecePhoto: Nikolai Karaneschev CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Statue of Alexander the Great, Thessaloniki GreecePhoto: Nikolai Karaneschev CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Athens quickly recovered from defeat, but the great empire developed from the Deli-Attic League was lost. However, Sparta dominated at the time with the help of the crafty Persians. However, the population was not satisfied with this and a series of conflicts arose between the states of which the Corinthian War became well known. The Second Attische Zeebond was also established.

Trade and industrial development increased prosperity, but much of the wealth was wasted on warfare and invested in slave-keeping. Furthermore, a group of displaced persons arose, e.g. exiles who sold themselves to the highest paying as mercenaries. The policy could not solve all these problems, so cooperation was required and a Pan-Hellenic idea gradually emerged with the aim of unity among the Greeks and revenge on the great enemy Persia.

However, the Greeks were trumped by Philip II of Macedon. Under his hegemony, a coalition of Greek city-states, including Athens, was defeated at the Battle of Chaerona in 338 BC. After Philip's murder, his son Alexander the Great followed in his father's footsteps and conquered the Persian Empire. Culturally, it was a period of rhetoric and philosophy and the visual arts were not about the gods but about the human ideal of beauty.

Hellenism and the Roman Period

Winged Nike of Samothrace highlight of the Helenistic period, GreecePhoto: Marie-Lan Nguyen in the public domain

Winged Nike of Samothrace highlight of the Helenistic period, GreecePhoto: Marie-Lan Nguyen in the public domain

The actions of Alexander the Great pushed the city-states out of their self-imposed seclusion and Greek culture began a triumphal procession. Political power was divided after the so-called "Diadochi Wars" by Alexander the Great's successors.

That battle culminated in the 3rd century BC. into three kingdoms, Ptolemaic Egypt, Seleukian Syria, of which Persia was a part, and Macedonia among the descendants of Antigonus the One-Eyed. The eastern elite in the cities were rapidly Hellenized by the emigration of Greek merchants, settlers and Mecedonisceh garrisons, so that "koiné", a corruption of classical Attic Greek, became the "lingua franca" of the Middle East. This spread of Greek culture is called Hellenism.

The Greeks, meanwhile, had not noticed that a great dangerous power had arisen from the west; the Romans. They soon became involved in the political and military struggles in Macedonia and Greece. From 215 BC. the Romans started military actions which in 196 BC. were completed with the termination of Macedonian rule over Greece.

The Romans soon came into conflict with the Achaean League upon which Corinth in 146 BC. was destroyed, the Achai League dissolved and Greece annexed to the "provincia" Macedonia. Most notably, the upper class of Roman society became Hellenized quite quickly and adopted many Greek ideas and philosophies.

Under Octavian Greece became the independent province of Achaia, but political freedom was lost and the economic situation deteriorated. In the intellectual field, however, great achievements were still being made by philosophers and writers, to which even young Roman intellectuals drew.

The Byzantine Period (330–1204)

Monasteries of Meteors from the Byzantine period, GreecePhoto: Takeaway at english wikipedia CC 3.0 Unported no change made

Monasteries of Meteors from the Byzantine period, GreecePhoto: Takeaway at english wikipedia CC 3.0 Unported no change made

As in Roman times, the Greek language and culture remained the basis for Byzantine civilization, but as a political and military power it played a subordinate role in the Byzantine Empire. Shortly before 400, Greece was occupied by the Visigoths and in the 6th and 7th centuries, Slavic hordes in Macedonia, Thessaly and Epirus wreaked havoc. They settled in the country and colonized the Peloponnese in the eighth century.

As a result of these invasions, a large Slavic-speaking population settled on Greek soil. At the end of the 7th century, Central Greece was incorporated into a separate administrative unit, a so-called "theme", which was headed by a military governor. Because Byzantium started to lose its grip, themes were created everywhere and from 800 onwards there was again effective rule from Byzantium. In the 9th and 10th centuries, Greece was a country without prominent cities.

The Christianization of Slavs was successful, also because they became part of the entire Greek culture. In 1054, the Eastern or Greek Orthodox Church, led by the Patriarch of Byzantium, seceded from the Church of Rome.

In the 10th to the 12th century, the Walachians settled in, among others, Thessaly and Aetolia. Despite all these strange elements and the Saracen piracy from Crete, the Greek coastal cities remained economically healthy due to the silk industry and the freight transport in the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Heavy taxes and feudal abuses brought Greece to the brink of collapse. In addition, Venice had enforced the trade monopoly in the Aegean and Black Sea through the help of Constantinople in the fight against the Normans in southern Italy.

The Latin period and the Turkish advance (1204 – c. 1460)

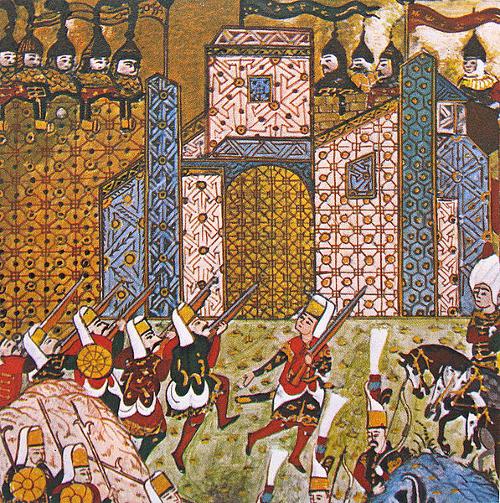

Ottoman Janissaries And Defending Knights Of St John, Siege Of Rhodes, 1522 Photo: Public domain

Ottoman Janissaries And Defending Knights Of St John, Siege Of Rhodes, 1522 Photo: Public domain

After the Fourth Crusade, the Byzantine Empire was defeated in 1204 and Greece fell apart. The Latin Empire of Constantinople ruled until 1261 but was recaptured in 1261 by the Greek Empire of Nica-Byzantium, which had also reclaimed the kingdom of Saloníki. In 1262 the Peloponnese was occupied again by the Palaeologists of Constantinople.

Thessaly followed in 1318 and Epirus in the west in 1336. In 1349 Epirus was lost to the Serbs again. In 1354 the Turks invaded Europe and occupied Thessaly in 1393. Around 1400 the Byzantine Empire only had the capital Constantinople, Saloníki and the Peloponnese. The Duchy of Athens of the Burgundian Othon de la Roche also had many occupiers. In 1311 it was conquered by Catalan mercenaries; In 1388, the Florentine banking family Acciaiuoli came to power until it was conquered by the Turks in 1456. The principality of Achaia-Moreia also fell to the Turks in 1461, who from that time ruled almost all of Greece.

The Greek islands were also occupied by many different powers, including the Turks, the Venetians, the Genoese and the Knights of John. In contrast to the Turkish occupation, the Franco-Italian rule in Greece hardly ever had a strong grip on people, culture or religion.

After the fall of the Byzantine capital Constantinople in 1453, Greece had a new centralistic state system. In this case the Turks ruled from Sofia, but it would take until 1566 before all the islands in the Aegean were conquered. Crete was not even conquered until 1669 and regularly belonged to Venice.

Revolts quickly took place, particularly against the Turkish governors who oppressed and extorted the population. The Sultan of the Turks, on the other hand, left the Greeks a great deal of independence, especially the position of the Greek Church was not affected. With the weakening of the Ottoman Empire, a national movement could emerge, aided moreover by the great powers who opposed the Turks as a constant threat. The French Revolution also stimulated the emergence of a national awareness. The Greeks' aspiration to break free from the disintegrating Turkish Empire was discussed by the great powers at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, but England was reluctant, as it wanted to keep the conquered Ionian Islands for itself.

The War of Freedom

Battle of Navarino, GreecePhoto: Public domain

Battle of Navarino, GreecePhoto: Public domain

In 1821, a revolt against the Turks broke out in the Peloponnese, which was to be the start of the war of independence. In this battle, the various parties were regularly winning. The Turks were backed by the Egyptians, and the Greeks were backed by the English and later received military aid from the Russians and the French. In 1827 the Battle of Navarino Bay was lost to the Turks and at the Peace of Adrianople in 1829, Turkey recognized Greece's independence. Nafplion became the capital, but in 1834 Athens was chosen for it.

It was not until 1833 that the Turks left the Acropolis in Athens. The north and most of the islands, including Crete, remained under Turkish or English domination.

Independent Greece

King George (1845-1913) I of GreecePhoto: George E. Koronaios CC 4.0 International no changes made

King George (1845-1913) I of GreecePhoto: George E. Koronaios CC 4.0 International no changes made

The brand new state was economically weak and politically very divided and was strongly influenced by the English, French and Russians. In fact, they wanted the restoration of Byzantine Greece with Constantinople and Asia Minor. The first "president", Capodistrias, was appointed president for seven years, but was assassinated as early as 1831. The English then wanted a European prince on the throne, and in 1832, King Louis I of Bavaria accepted the Greek crown for his son Otto, who first entered Greek soil in 1833.

Otto I was a strong supporter of a central authority and thus came into conflict with the aristocracy and the clergy who held much power under the Turks in the region and who were now in danger of losing it.

A rebellion in 1843 - carried out by the "Russian Party" - forced him to promise a constitution to Greece. The king was also forced to replace his Bavarian minister with Greeks. This constitution was passed by the parliament in 1844 and accepted by the king.

Greece suffered a failure during the Crimean War; when it wanted to support revolts in the still Turkish Epirus and Thessaly, an Anglo-French naval squadron occupied Athenes port, Piraeus (1854–1857). In October 1862, King Otto was forced to resign by a revolt. Under the influence of the English, the parliament offered the throne to the Danish Prince William of Denmark, who became king under the name of George I. He accepted his government on October 31, 1863 and would rule until 1913. As a reward and received a kind of wedding gift the Greeks of England in 1864 the Ionian Islands. In 1866 there was a revolt of the Cretans, supported by the Greeks, against the Turks.

At the same time, the Greeks tried to acquire Epirus and Thessaly but were opposed by the great powers. In 1881, provisions from the Congress of Berlin were cashed in, and most of Thessaly and a small portion of southern Epirus were assigned to Greece. In 1896 another revolt on Crete and now Greece sent troops to Macedonia, where the Greeks suffered a great defeat. Even now, the great powers imposed a settlement on the Greeks: Turkey received some border corrections in the north but had to allow Crete to become autonomous with a son of the Greek king as governor.

After a number of revolts, it resigned in 1906 and the great powers once again decided on the fate of Crete. The Greeks considered this interference as a great humiliation and this triggered a wave of nationalism, which in 1910 Venizelos became Prime Minister. It was only after the Balkan Wars that Greece was able to expand its territory with Macedonia, part of Southern Epirus and a number of Aegean islands, including Crete.

After the violent death of George I in 1913, his son and successor Constantine I faced the First World War. Immediately problems arose between the king and Venizelos. The king was a brother-in-law of the German Kaiser Wilhelm II, and he wanted to remain neutral. Venizelos chose the Allies, after which Venizelos was fired by the king in 1915. In 1916 he founded a counter-government in Saloníki. At the same time, the Allies blocked the coast of the central and south of the mainland that remained loyal to Constantine.

In June 1917, Constantine was forced to abdicate in favor of his son Alexander and Athens was occupied by the French. Venizelos now established his authority across the country and declared war on Germany in June 1917. Greece took part in the offensive in the fall of 1918 that led to the capitulation of Bulgaria in 1918.

At the Treaty of Neuilly in November 1919, Greece acquired the Bulgarian western Thrace. The Peace Treaty of Sèvres in 1920 stipulated that the Greeks would receive European Turkey and Smyrna (now: Izmir). The Turks, led by Kemal Atatürk, refused to cooperate. After the death of King Alexander in October 1920 and the return of Constantine, Venizelos was put aside. Only England supported the Greeks in their pursuit of expansion in Asia Minor, which led to a crushing defeat against the Turks in 1922.

George II of Greece, King of the HellenesPhoto: Public domain

George II of Greece, King of the HellenesPhoto: Public domain

The king resigned in favor of his son George II, who was in turn deposed in 1923. At the Peace of Lausanne in 1923, a large-scale Greek-Turkish population swap was decided and Greece had to acquiesce in the annexation of the Dodekánesos by Italy. This part of present-day Greece had already been conquered by Italy from the Turks in 1912. Furthermore, the Greeks had to return Adrianople and Smyrna to Turkey.

In the 1920s Greece remained a country of great political contradictions and in 1924 it officially became a republic with the military Koundouriótis as president. From January to August 1926, there was a brief military dictatorship under General Pángoulos. After the 1928 elections, Venizelos returned to power and reconciled with Turkey. In the period up to World War II, most cabinets were overthrown by the military. In 1935, King George II was recalled from exile after a popular vote, but was soon succeeded by the dictator Metaxas, an admirer of Hitler and Mussolini.

World War II and Civil War

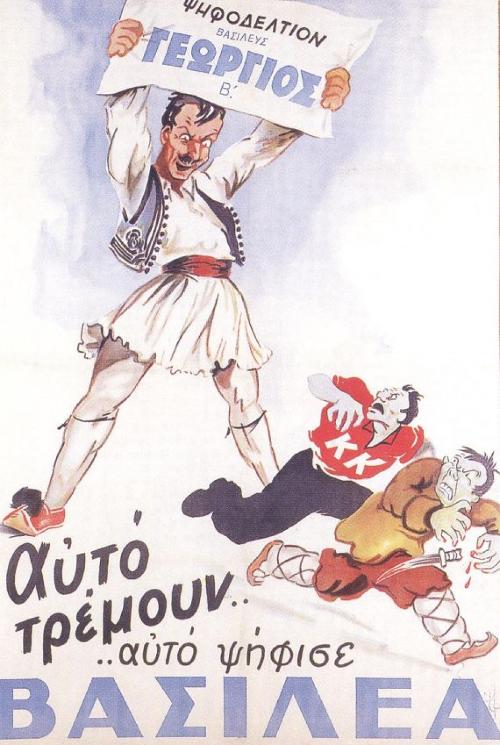

Anti-Communist poster, GreecePhoto: Public domain

Anti-Communist poster, GreecePhoto: Public domain

Before World War II, Metaxas tried to keep friends with both Germany and England for economic reasons. In October 1940 the Italians invaded Greece but met very fierce resistance and could only conquer Greece in April 1941 with the help of the Germans. In May of the same year, Crete was also conquered by the Germans. Most of the country was occupied by Italy, Germany occupied Piraeus and Saloníki, among others. A small part of Greece was annexed by Bulgaria. The king and the government fled abroad. The board was in the hands of a number of German front men, including Tsolakoglou, Logothetopoulos and Rallis. Soon all kinds of resistance movements arose that even competed with each other, but which did cooperate closely with the British.

Meanwhile, the emigrated king and the government had little more to say and, with the approval of the British, in September 1944 this led to a government of "National Unity" with Prime Minister Papandreou, which settled in Athens on October 18, 1944. The British had already landed in Greece in September and demanded the disbandment of all guerilla groups. One of these groups, the EAM, refused and the ELAS took over most of Greece but was subdued by the British that same year. Papandreou then resigned and the king only wanted to return if the people explicitly asked for it. As a result of this situation, the Archbishop of Athens was proclaimed regent.

The struggle with the ELAS was halted after negotiations in early 1945, but the communists remained militarily active from the north. Elections were held in March 1946 and a popular vote led to the return of the Greek King George II in September.

The Dodekánesos and the territories annexed by Bulgaria got Greece back at the Peace of Paris in 946. Financial compensation by Italy was also arranged here. And on top of that came the help of the United States under President Truman. King George II died in 1946 and was succeeded by his brother Paul I. Under his rule, the communist uprising that had lasted for years came to an end in 1949. In 1947 the civil war was raging at its worst; the loyalist troops were led by Papagos; the well-armed communists, led by the Stalinist "general" Markos, carried out raids through the country and deported 26,000 Greek children to neighboring communist countries. In 1948 the battle ended due to the invasion of an English army, disagreement among the communists, supplies of American weapons to the government forces and due to lack of weapons among the communists.

Also important in these years was the break between Stalin of Russia and Tito of Yugoslavia in 1948, which closed the Yugoslav-Greek border in 1949.

The fifties and sixties

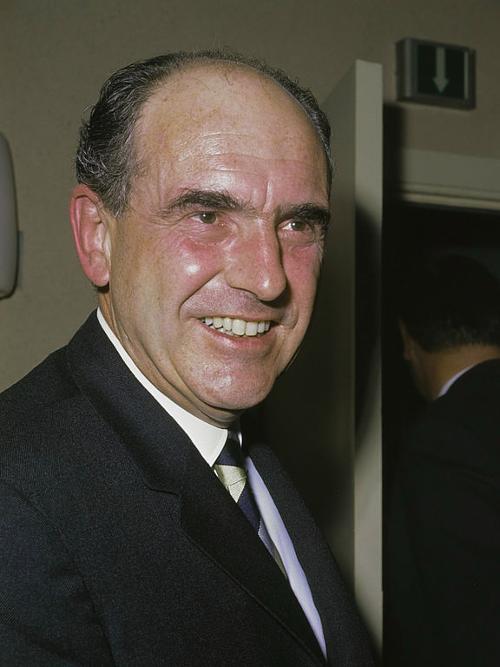

Papagos GreecePhoto: Van Duinen/Anefo in the public domain

Papagos GreecePhoto: Van Duinen/Anefo in the public domain

In 1952 Greece joined NATO and under Papagos of the new party "Greek Concentration" a more stable time followed and relations with neighboring countries improved. In 1954, an alliance was even concluded between Greece, Yugoslavia and Turkey. However, this alliance had little chance of success, partly due to the Cyprus question, which caused relations between Greece and Turkey to explode.

The Cypriot movement seeking affiliation with Greece (enosis) sparked riots in Greece itself in 1954 and the matter was referred by Papagos to the United Nations. In 1955, the conflict on the island under the leadership of Grivas began to escalate, bringing relations between Greece and Turkey to an all-time low. Papagos died in 1955 and was succeeded by Karamanlis, the leader of the new National Radical Zunie (ERE) party. Karamanlis sought to resolve the Cypriot conflict through negotiations and remained loyal to NATO. The Republic of Cyprus was founded in 1960.

In 1963, Karamanlis resigned when the king did not follow government advice to postpone a state visit to England. The constant involvement of the crown in politics had also been a thorn in his side for some time.

In two consecutive general elections, the party of the reformist Papandreou won many seats in parliament.

In May 1965, a secret organization of left-wing army officers was discovered, to which Papandreou's son is said to have supported. Papandreou himself wanted to purge the army of "anti-democratic and fascist figures", in fact his opponents. King Constantine II, the successor of Paul I, who died in 1964, refused to resign the minister of defense, who was an opponent of Papandreou in the cabinet. In July 1965 the Papandreou government resigned and violent pro-Papandreou demonstrations took place all over Greece. After the election, the king tried to form cabinets of anti-Papandreou people. The parliamentary-constitutional crisis continued and on April 21, 1967, a group of ultra-right officers staged a coup d'état, the so-called "colonels".

Military regimes (1967-1974)

Flag of Greece adopted by the JuntaPhoto: Public domain

Flag of Greece adopted by the JuntaPhoto: Public domain

Constantine accepted the situation and appointed the politician Kollias as prime minister of a government controlled by soldiers such as Papadopoulos and Patakos. In December, Constantine made a feeble attempt to overthrow the regime. After this he fled to Italy to go into exile and the military Papadopoulos was appointed president and Zoitakis as regent for the fled king. In his first reign, Papadopoulos took more and more power until he eventually became regent in 1972. Finally, on June 1, 1973, he proclaimed the republic and the monarchy came to an end.

Already on November 25, 1973, the Papadopoulos government was overthrown by a number of generals led by Brigadier General Joannidis, one of his former allies. Due to the bad economic situation and the decline in the Cyprus question (the Turks landed on the north coast of Cyprus in 1974 while the Greek regime was forced to watch impotently), a large number of officers demanded that the military make way for a civilian government.

Restoration of the civilian government

Konstantin Karamanlis GreecePhoto: Institution:Greek State General Archives CC 3.0 no changes made

Konstantin Karamanlis GreecePhoto: Institution:Greek State General Archives CC 3.0 no changes made

In July 1974 it was decided to recall former Prime Minister Karamanlis from Paris, and he appointed a "cabinet of national unity". The 1952 constitution was also reinstated and the form of government was to be chosen by referendum.

Negotiations with the Turks over Cyprus failed and in August 1974 the Turks conquered nearly 40% of the island, after which the situation was presented to the United Nations.

On November 17, 1974, the elections were won by a large majority (56%) by Karamanlis' party, the New Democracy (ND). The third Kainet-Karamanlis held a referendum on the form of government and nearly 70% of the voters were against a return of the monarchy. In June 1975 a new constitution was passed and K. Tsatsos became the new president.

In the course of 1976, tensions between Greece and Turkey increased again and the status of the Aegean Sea also became a disagreement. Greece's return to NATO's command structure was also fraught with problems because Turkey was also a member of the alliance. It was not until March 1978 that there was any improvement in relations with Turkey.

Period from 1980

Andreas Papandreou GreecePhoto: Eric Koch/Anefo in the publc domain

Andreas Papandreou GreecePhoto: Eric Koch/Anefo in the publc domain

The elections of November 20, 1977 were again won by Karamanlis and in his fourth term, Greece joined the European Community and was elected president in 1980. In 1981, the Panhellenic Socialist Party (PASOK) became the country's largest party and Andreas Papandreou became Prime Minister. His proposed reforms, including in the social field, could only partially be realized. In 1985, the non-party Christos Sartzetakis was elected president and PASOK lost the absolute majority in the elections. As the largest party, however, the PASOK was allowed to continue to rule.

The 1989 elections again failed to produce a winner and until April 1990 Greece was ruled by a number of interim cabinets. Konstantinos Mitsotakis managed to form an ND government and Karamanlis was again elected head of state. From 1990 onwards, the many refugees from Albania caused major problems in Greece. Relations with the other EC countries came under pressure due to the Macedonia issue. The Greeks withheld the EC's recognition of the independent republic of Macedonia because of fear that the Macedonians would make claims to the Greek province of the same name.

In 1993 ex-king Constantine was allowed to visit Greece again as a "citizen". That same year, Papandreou's PASOK won the elections and became the new Prime Minister. In March 1995, President Karamanlis resigned and was succeeded by Kostas Stefanopoulos, a non-party politician.

Relations with Turkey reached a low point in January 1996 over a tiny uninhabited Greek island. It even went so far as to nearly start a war between the two countries. Prime Minister Papandreou died in June, who had already been succeeded by Konstantinos Simitis in January. Early elections were held in September and were won by PASOK, which retained its majority in parliament.

The ongoing conflict with Albania over the position of the Greek minority in that country and the Albanians working in Greece appeared to be improving with the signing in March 1996 of a friendship treaty. Papandreou died on June 23, 1996.

Relations with Turkey remained tense. In February 1997, Athens threatened to block the expansion of the European Union to include Eastern European countries, if the Turkish Cypriots were allowed to participate in the negotiations for the accession of Cyprus. The fact that in 1998 Greece defended the controversial Greek-Cypriot decision to purchase Russian anti-aircraft missiles led to very serious tensions.

Greece changed this position when Turkey announced that it regarded the placement as an act of war. In June 1998, the Greek government thwarted an EU proposal for economic aid to Turkey, through which the EU sought to improve relations with Turkey.

In February 1999, Turkish commandos arrested Kurdish PKK leader Öcalan after leaving the Greek embassy in Kenya, where he had taken refuge. Serious mistakes on the part of the Greek side had made the arrest possible and put the Greek government in a difficult position, especially as the Greek population - sympathetic to the Kurdish struggle for independence - interpreted the incident as a humiliation by arch-enemy Turkey. Prime Minister Simitis fired three ministers he held partly responsible for the mistakes, including Foreign Minister Theodoros Pangalos. This was succeeded by Georgios Papandreou, the son of statesman Andreas Papandreou.

Greece, as a member of NATO, took an ambiguous stance in the Kosovo war in 1999. The Greek people traditionally feel connected to the Serbian, which also adheres to the Orthodox Christian faith. A large majority of Greeks strongly opposed the NATO attacks on Serbia from the end of March. The Greek government initially appealed to NATO to cease the bombing, but had to reconsider its position under pressure from the United States. This put Prime Minister Simitis in a dire situation, as he had to keep the nationalists in his party happy and anti-NATO actions in Greece continued. Cooperation with NATO was therefore not easy.

In early 1999, the Greek-Cypriot decision to abandon the placement of Russian S300 anti-aircraft missiles. This initially eased Greco-Turkish tensions. However, the Greeks did not get out of their contract with Russia. On February 9, Cyprus and Greece signed a treaty on the placement of the missiles in Crete. Turkey reacted as if stung by a wasp. However, relations with Turkey improved significantly after a major earthquake hit this country on August 17. Greece immediately came to the aid of Turkey directly and supported an EU proposal for a large-scale aid program.

21st century

Sinitis GreecePhoto: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Sinitis GreecePhoto: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

On February 8, 2000, the Greek Parliament elected Kostas Stefanopoulos as president for a second five-year term by a large majority.

In the parliamentary elections on April 9, 2000, New Democracy was defeated by PASOK in a tense race. PASOK received 43.8% of the vote, against 42.7% for New Democracy. The election results did not lead to drastic cabinet changes. Immediately after his victory, Prime Minister Simitis stated that he wanted political continuity in connection with the desired Greek accession to the EMU and the rapprochement with Turkey. On April 25, 2000, Parliament approved the new government program, including the key issue of strengthening Greece's position within the European Union.

PASOK's election victory enabled Prime Minister Simitis to continue his successful economic austerity policy. In the spring of 2000 inflation was only 2.9% for the first time in 30 years. Greece thus qualified for participation in the European Monetary Union. The European Parliament adopted a resolution by a large majority on May 18, 2000, calling for Greek accession to the Eurozone as of January 1, 2001. On June 19, the Council of Ministers was officially approved.

Since major earthquakes hit Greece and Turkey in 1999, there has been a cautious rapprochement between the two countries. In 2000, five cooperation treaties were signed in the fields of economy, science, culture, maritime trade and customs. In October, both countries took part in a joint NATO exercise in the Aegean Sea, initially seeing the planned presence of Greek military and equipment on Turkish territory as a breakthrough.

However, the relationship came under pressure again when an old military disagreement over the airspace of two Greek islands surfaced again. Ultimately, Greece withdrew from the exercise. Since March 2004, ND has formed a government headed by Prime Minister Karamanlis. Giorgos Papandreou is now leader of the opposition party PASOK.

In February 2006, Prime Minister Karamanlis reshuffled his government to revitalize his policies. The Minister of Foreign Affairs, Petros Molyviatis, has been replaced by Mrs. Dora Bakoyannis.

Greece unfortunately still faces violence perpetrated by extreme left-wing (anarchist) groups. At the end of 2005, attacks were committed on the Ministries of Development and Finance. Anarchists often cause unrest in Athens by setting fire to banks and other buildings with gas bottles.

In September 2007 Karamanlis will receive a mandate for a new period. In March 2008, Greece blocked Macedonia's access to NATO in connection with a dispute over the naming of this former Yugoslav republic. In December 2008, serious disturbances broke out after police shoots dead a 15-year-old boy in Athens. In October 2009, Pasok won the elections and George Papandreou became the new prime minister.

At the end of 2009, the full extent of the Greek debt crisis begins to penetrate. Greece is no longer considered creditworthy because of the excessively high national debt. Papandreou announces substantial cutbacks, which will lead to riots with the population. There is severe action in the public sector and the retirement age is rising sharply. In February 2010, European government leaders pledged to help Greece solve the debt crisis, but on hard terms. A huge amount will be made available in April and May. Greece will have to cut even harder in return for this. The unions are calling for a general strike. At the end of 2011, Papandreo gets into trouble and the technocrat Lucas Papademos becomes interim prime minister. There are elections in May 2012, but there is no clear winner. President Papoulias calls new elections that are won by new democracy, without getting a majority. Antonis Samaras forms a coalition with, among others, the PASOK. In 2013 the employment figures hit new negative records. More than 60% of Greek youth are unemployed. Cuts remain necessary, as a result of this the plug will be pulled from Greek state television in June 2013.

Alexis Tsipras GreecePhoto: Karpidis CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Alexis Tsipras GreecePhoto: Karpidis CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

At the end of 2013, there were problems with the support of the extremely rightwing party Golden Dawn. In December 2013, the budget for 2014 will be approved and six years of recession may come to an end. In May 2014, Syriza, the radical left anti-austerity party, wins the European elections with 26.6% of the vote. In January 2015, Syriza's Alexis Tsipras becomes the new prime minister in a coalition government of nationalists. The years 2015 and 2016 are dominated by the debt crisis and the refugee crisis. The European central bank comes to the aid of the Greeks in exchange for austerity. The Greek islands are flooded by refugees, the flow to the rest of Europe is difficult. In the summer of 2016, there is still much talk about debt relief for the Greek economy. In April 2017, an agreement was reached on the continuation of the support program for Greece. In return, Greece must take new measures in the field of taxes and pensions in 2018. In june 2018 Greece sign an historic agreement resolving a 27-year-long dispute over the official name of Macedonia. Centre-right New Democracy party wins landslide at early elections in July 2019, and leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis becomes prime minister. Katerina Sakellaropoulou was elected president by parliament in January 2020, and took office in March, becoming Greece's first female head of state. The refugee crisis is still a major problem, camp Moira in Lesbos is set fire in September 2020. In 2021, the COVID pandemic and the refugee issue are the main problems to be addressed.

Sources

DuBois, J. / Greece

Times Books International

Europese Unie : vijftien landendocumentaties

Europees Platform voor het Nederlandse Onderwijs

Gerrard, M. / Griekenland

Kosmos-Z&K

Koster, D. / Griekenland

ANWB

CIA - World Factbook

BBC - Country Profiles

Copyright: Team The World of Info