ANDALUSIA

History

History

Popular destinations SPAIN

| Andalusia | Catalonia | Costa blanca |

| Costa brava | Costa del sol | El hierro |

| Formentera | Fuerteventura | Gran canaria |

| Ibiza | La gomera | La palma |

| Lanzarote | Mallorca | Menorca |

| Tenerife |

History

First occupants

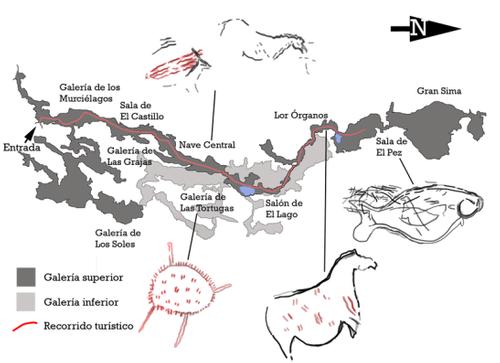

From about 100,000 to 26,000 years BC, during the last ice age, Andalusia was inhabited by Neanderthals. The decline of the Neanderthals in Europe started about 35,000 BC, but recent excavations have shown that these people in Andalusia up to about 26,000 years BC. After the Neanderthals, Homo sapiens took over, probably from North Africa and attracted by the climate, forests and the presence of many different animals. These hunters and gatherers left between 20,000 and 16,000 BC. many beautiful petroglyphs behind, including in Andalusian caves such as Cueva de Ardales, Cueva de la Pileta and Cueva de Nerja.

Overview of the Cueva de la Pileta, indicating the site of petroglyphsPhoto: Falconaumanni CC4.0 International no changes made

Overview of the Cueva de la Pileta, indicating the site of petroglyphsPhoto: Falconaumanni CC4.0 International no changes made

Approx. 6000 BC. The Neolithic or New Stone Age reached Spain from Egypt and Mesopotamia, and from that time on agriculture became increasingly important. About 3,500 years later, the people of Los Millares, near present-day Almería, were able to work copper for the first time, and that was the first time that a metalworking culture emerged. During this time, especially in the area of Antequera (just north of Malaga), many megalithic monuments were erected, as at that time in countries such as France, Great Britain and Ireland. Approx. 1900 BC. the agrariars of Al Argar from the province of Almería were the first to work bronze, which was much stronger than copper.

Merchants and Conquerors

The development of Andalusia attracted seafaring traders from more developed societies around the Mediterranean. Later, those merchants were replaced by imperialist states seeking not only merchandise but political control over territories.

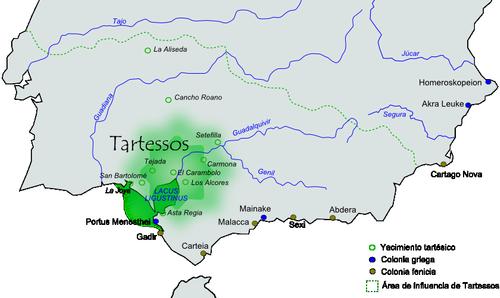

Around 1000 BC. attracted the thriving culture of western Andalusia the attention of the Phoenicians, seafaring traders from present-day Lebanon in West Asia, who introduced olives, grapes and donkeys to this area of Spain. Perfume, ivory, jewelry, oil, wine and textiles were exchanged for silver and bronze and trading settlements were established, including present-day Cádiz (then: Gadir) and Huelva (then: Onuba). In the 7th century BC. arrived the Greeks, who had about the same merchandise as the Phoenicians. The influences of the Phoenicians and the Greeks created a mixed culture that would come to be known as the Tartessos culture. It is not really known what exactly this culture represented. In the literature of that time there is talk of enormous wealth, but whether it concerned a city or a region, for example, is unclear. It is known that bronze was replaced by iron at that time.

Tartessos culture in Western Andalusiaa; Gadir is the current CádizPhoto: Redtony CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Tartessos culture in Western Andalusiaa; Gadir is the current CádizPhoto: Redtony CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Carthage, Rome and the Visigoths

Cordoba Andalusia Roman BridgePhoto: Michel wal CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Cordoba Andalusia Roman BridgePhoto: Michel wal CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

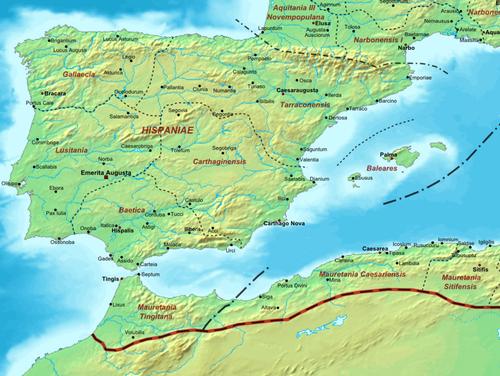

From the 6th century BC. Carthage, a former Phoenician colony, dominated trade in the western Mediterranean. Already in the 3rd century BC. would completely change this image, because a new Mediterranean power arose: Rome! The Romans won, with Siciliaat stake, the First Punic War (264-241 BC), but Carthage still managed to conquer southern Spain. During the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), Carthaginian general Hannibal crossed the Alps with his elephants and threatened the city of Rome. However, the Romans invented a ruse, they opened a second front and sent army units to Spain to fight against Carthage there as well. This battle was won by the Roman soldiers of General Scipio Africanus, after the Battle of Ilipa (near present-day Seville) in 206 BC. they controlled the entire Iberian peninsula. Built on the battlefield, Itálica was the first Roman settlement in Spain.

During Roman rule, Andalusia one of the richest and civilized regions of the Roman Empire, with Córdoba (then: Corduba) as the most important city. Rome brought Andalusia aqueducts, temples, theaters, amphitheaters, bathhouses, languages (Castilian, Portuguese, Catalan and Galician are directly descended from the Latin colloquialism of Roman settler soldiers), a fairly large Jewish population and in the 3rd century AD. Christianity. It is striking that two successive Roman emperors expanded their empire from Itálica in Andalusia, Trajan (98-117) and Hadrian (117-138).

At the end of the 4th century, the Huns overran Europe from Asia, and several Germanic tribes fled west, including the Visigoths. They conquered the Iberian Peninsula in the 6th century, because the Roman Empire was in decline at that time. From 552 to 622 Andalusia just a little further out of the Byzantine Empire, but after that the Visigoths held sway again.

Roman Spain c. 400 AD.Photo: Public domain

Roman Spain c. 400 AD.Photo: Public domain

Visigoth Spain, approx. 700Photo: Public domain

Visigoth Spain, approx. 700Photo: Public domain

After the Prophet Muhammad's death in 632, Islam was initially spread across the Middle East and Africa, but it wouldn't be long before Muslims turned their sights on Spain. In 711, Tariq ibn Ziyad, the governor of Moroccan Tangier, defeated the Visigoth king Roderik with a mostly Berber army at the Rio Guadalete in Cádiz province. In a few years the entire Iberian Peninsula was in the possession of the Muslim Moors, with the exception of some areas in the far north in the mountains of Asturias. For the next four centuries the Moors would rule the Iberian Peninsula and for the next four centuries they were still a force of power.

Tariq ibn Ziyad (670-720)Photo: Public domain

Tariq ibn Ziyad (670-720)Photo: Public domain

One of the most developed areas of Moorish Spain would become Al-Andalus, present-day Andalusia. The borders of Andalusia shifted regularly due to Christian attacks in the area, but until the mid-11th century, Christians were not much of a threat to the Moors. There was even a kind of freedom of religion for the Jews and the Christians in Andalusia, but for that they had to pay high taxes. That was a major reason for many Jews and Christians to convert to Islam or flee to the Christian North. The Christians in Moorish territory became 'Mozaraben;called Mozárabes' in Spanish;those who converted to Islam were called 'muwallads' in Spanish. The Moors also brought about a cultural boom in Andalusia with the construction of beautiful palaces, mosques, the design of beautiful gardens and the foundation of a number of universities.

Emirate and Caliphate of Córdoba

In 750, the most powerful Muslim rulers to date, the Omayyads of Damascus, were forcibly deposed by the revolutionary Abassids, who moved the caliphate to Baghdad. The Ommayad Abd ar-Rahman I escaped the massacre, initially fled to Morocco and then left for Córdoba, where in 756 he proclaimed himself an independent Emir. The resulting dynasty would more or less unite Al-Andalus for about 250 years. In 785, the Mezquita (mosque) of Córdoba, a pinnacle of Islamic architecture, was opened to prayer.

Omayyad Caliphate at the height of its power Photo: Gabagool CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Omayyad Caliphate at the height of its power Photo: Gabagool CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In 929, Abd ar-Rahman III proclaimed himself Caliph of Córdoba, in response to the rising power of the North African Fatimid dynasty. The Caliphate of Córdoba at its height ruled about two thirds of the Iberian Peninsula and the city of Córdoba was the largest city in Europe at the time and the center of many developments in the fields of science such as astronomy, medicine, mathematics., philosophy, history and botany.

Later in the 10th century, General Al-Mansur terrorized the Christian north of Spain and destroyed, among other things, the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain. After the death of Al-Mansur, the Caliphate of Córdoba fell apart into many kingdoms or 'taifas', ruled by often Berber generals.

Almoravids and Almohads

Seville would become the strongest 'taifa' of Al-Andalus from about 1040, ruled an area from southern Portugal to Murcia in southeastern Spain from 1078 and ensured peace and prosperity. Meanwhile, the Christian north made itself heard more and more, and to the horror of Seville, Toledo was conquered in 1085 by Christians of Castile. Seville quickly enlisted the help of the strict Islamic sect of the Almoravids, Berbers from the Sahara who had conquered Morocco. The Almoravids did indeed come, defeated Alfonso VI of Castilia, but took over power in Al-Andalus. Al-Andalus was ruled as a colony from Marrakech and Jews and Christians were persecuted. However, this domination did not last long, revolts were the order of the day and from 1143 the whole area fell apart again into a number of taifas.

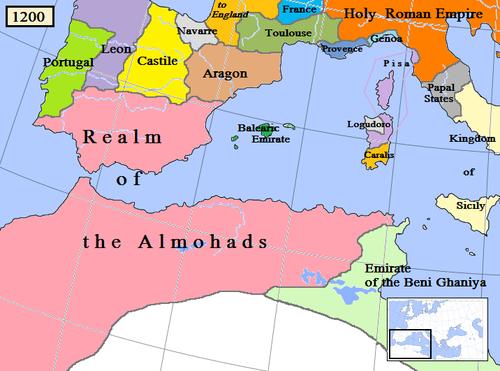

This situation would not last long either, because the Almohads, took control of the Almoravids in Morocco, conquered Al-Andalus in 1173 and proclaimed Seville the capital of their entire territory. Al-Andalus was considerably reduced at the time, and now ran only south of Lisbon to just north of Valencia. Again, Al-Andalus was regularly attacked by Christian forces, and in 1195 a large Castillian army was defeated by Almohadian ruler Yusuf Yakub al-Mansur. However, this caused several Christian fiefdoms to join hands and battle the Almohadic ruler. In 1212, the united armies of the Christian kingdoms of Castilia, Aragón and Navarre defeated the Almohads at Las Navas de Tolosa, north of Jaén. Fuss over a succession issue in 1224 allowed Castilia, Aragón, Portugal, and Léon to advance further south. The monarch of Castilia, Fernando 'El Santo' III, conquered the strategically important Baeza in 1227, Córdoba in 1236 and Seville in 1248.

Almohad Empire around 1200Photo: Gabagool CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Almohad Empire around 1200Photo: Gabagool CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

At that time, the Emirate of Granada was the only area under the control of the Almohads, in this case of the Nazari Dynasty or Nasrid of Mohammed ibn Yusuf ibn Nasr. The area comprised roughly the present-day provinces of Granada, Málaga and Almería and would remain the last Muslim area on the Iberian Peninsula for about 250 years. The Nasrid were at the peak of their power in the 14th century under Yusuf I and Mohammed V. The eventual decline of the Nasrid was caused by two things: In 1476, Emir Abu al-Hasan refused to pay taxes to any longer. Castilia, and in 1479 the two powerful Christian states of Castileaand Aragón and in 1482 undertook a final crusade against Granada, the Reconquista. Granada, meanwhile, was already weakened by internal problems and Málaga was conquered in 1487 and Granada in 1492 without too much difficulty. The last emir, Boabdil, was allowed to keep a fief south of Granada, but left for Africa after a year.

Emirate of Granada TerritoryPhoto: Redtony CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Emirate of Granada TerritoryPhoto: Redtony CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Well into the 13th century, Muslims who continued to live in areas under "Christian" control, the so-called "mudéjars," did not have much to fear. It was not until 1264 that that changed with the revolt of the mudéjars of Jerez de la Frontera against increased taxes and tighter rules, making them compulsory to celebrate Christian festivals, for example. After a five-month battle, the mud jars were driven to Granada and North Africa, along with the mud jars of Seville, Córdoba and Arcos.

The new Christian rulers in southern Spain donated large pieces. land to nobles and knights who had played an important role in the Reconquista. Fernando III's son, Alfonso 'El Sabio' X, who reigned from 1252-1284, made Seville one of the capitals of Castileaand gathered around him a number of mainly Jewish scientists who translated texts from ancient times into Castillian. The Castillian monarchy was plagued by family rivalries and attacks from the nobility at the time, and Catholic kings took over Spain in the late 15th century.

An outbreak of plague and some poor harvests in the 14th century the Jews were blamed, and pogroms followed in the last decade of the 14th century. Some Jews, the so-called 'conversos' decided to be converted to Christians, others fled to the Islamic Granada. In the 1980s, the 'conversos' were hunted by the Spanish Inquisition and accused of still practicing their faith.

Cathedral of Teruel in mudéjar- building style Photo: Escarlati CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Cathedral of Teruel in mudéjar- building style Photo: Escarlati CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

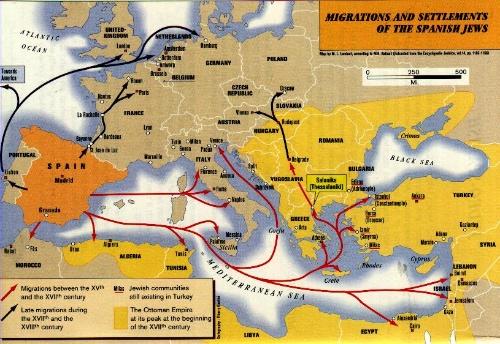

In 1492, under pressure from the Grand Inquisitor Tomás de Torquemada (1420-1498), Isabel and Fernando decided that any Jew who refused to be converted should be exiled. Between 50,000 and 100,000 Jews were converted at the time, but more than 200,000 Jews refused, and these so-called Sephardic Jews emigrated to other Mediterranean areas.

Migration directions of Spanish Jews ( sefardim), 15th to 18th centuryPhoto: Encyclopaedia Judaica CC BY 3.0 NO no changes made

Migration directions of Spanish Jews ( sefardim), 15th to 18th centuryPhoto: Encyclopaedia Judaica CC BY 3.0 NO no changes made

The task of converting the Muslims of Granada lay in the hands of Cardinal Francisco Jiménez (Ximenez) de Cisneros, executor and "boss" of the Inquisition. He forced many Muslims to convert to Christianity, burned Islamic holy books and banned the Arabic language.

All this led to a failed Muslim uprising in Las Alpujarras in 1500, after which the Muslims could choose, convert or Granada leave. Most Muslims, 'Moriscos', then allowed themselves to be converted, but after the fanatical Catholic King Philip II banned the Arabic language, Arabic names and even 'Morisco' clothing, a new Las Alpujarras revolt spread across the south of Andalusia. This uprising, which lasted two years, was won by Philip, after which the Moriscos were initially deported to Western Andalusia and the north of Spain. Between 1609 and 1614, almost all Muslims were expelled from the Iberian Peninsula by Philip III.

Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros (1436-1517)Photo: Public domain

Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros (1436-1517)Photo: Public domain

The accidental discovery of America by Christopher Columbus would become of great significance, especially for the river port of Seville. During the reign of Charles I (1516-1556), the king of Spain and better known as the Roman German Emperor Charles V, 'conquistadors' like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro conquered large tracts of land from the American mainland and brought enormous quantities of gold and silver to Spain, one fifth of which was collected by the Spanish crown.

Seville became the center of world trade at that time and was the most important city in Spain until the late 17th century, although Madrid was declared the capital of Spain as early as 1561. The population of Seville grew in barely a century from 40,000 in 1503 to 150,000 in 1600. But cities such as Cádiz and to a lesser extent Córdoba, Granada and Jaén also participated in these golden years. At the end of the 17th century, things quickly deteriorated with the position of Seville as an important port. Silver journeys from America declined rapidly and the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, the lifeline to the Atlantic Ocean essential to Seville, slowly silted up. In addition, epidemics and poor harvests caused the death of some 300,000 Andalusians. In 1717, Seville's prominent place in trade with America was taken over by the seaport of Cádiz, which reached its peak in the 18th century.

In the 18th century there were initially a number of economically important developments. A new road from Madrid to Seville and Cádiz was built, more agricultural areas were opened up and the population was greatly increased by people coming from other areas of Spain to Andalusia. By 1787 the population had risen to 1.8 million.

Very bad news for Cádiz and therefore also for Andalusia was the loss of the American colonies at the beginning of the 19th century. The port city of Cádiz was in fact totally dependent on trade with these colonies and when this stopped Andalusia ran out. In the course of the 19th century it fell into severe economic crisis and became one of Europe's least developed regions with huge income disparities between some wealthy people and the rest of the population. The early 19th century also marked the end of Spain as a naval power. In 1805 a combined Spanish-French fleet during the Napoleonic Wars at Cabo de Trafalgar, south of Cádiz, was defeated by the British under the command of Admiral Horatio Nelson (1758-1805), who was killed in this naval battle. In 1836 and 1855 a lot of church and congregation land was auctioned to reduce the national debt, but this was again at the expense of farmers who saw their pasture land go up in smoke and unemployment, illiteracy, disease and hunger lay before the many, especially day laborers, lurk. Peasant revolts broke out, inspired in part by anarchist ideas of the Russian Michael Bakunin, which were, however, suppressed with a heavy hand. It was at this time that the powerful anarchist trade union Confederacion Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) was also founded in Seville in 1910, which in Andalusiaaalready had 93,000 members in 1919.

Spanish Civil War

In fact, the polarization of Andalusian society and politics was true for all of Spain, and in the course of the 20th century, Spain was heading for a real civil war.

In 1923, the general born in Jerez de la Frontera, Andalusia, Miguel Primo de Rivera launched a military coup along with the great socialist union Union General de Trabajadores (UGT). King Alfonso XIII appointed Primo de Rivera as chairman of a military directorate, remained monarch, but in fact had nothing more to say. As a result of bad economic times, discontent in the military and the gains of republican parties in local elections in April 1931, King Alfonso XIII fled to Italy. Earlier, in January 1930, Primo de Rivera had already resigned due to continued criticism of his policies and was succeeded by General Damasco Berenguer.

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbanejo (1870-1930)Photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-09414 CC3.0 Germany no changes made

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbanejo (1870-1930)Photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-09414 CC3.0 Germany no changes made

The Spanish Civil War drove a wedge between families, groups of friends and communities. Both sides committed terrible massacres, especially in the first weeks of the war. The rebels, calling themselves nationalists, murdered tens of thousands of republicans, but they too did not stand idle, killing about 7,000 priests, monks and nuns alone. In republican areas, many towns and cities were run by anarchists, communists or socialists. Andalusia became an anarchist stronghold, where private property was banned and churches and monasteries were often set on fire. Landowners' farms were occupied by peasants and some 100 agricultural communes were established.

The situation was soon apparent: towns with garrisons supporting the rebels, and most of them, fell immediately into the hands of the nationalists, for example in the Andalusian cities of Cádiz, Córdoba and Jerez de la Frontera. Seville was in the hands of the nationalists in two days, Granada a few days later. The conquest of Granada cost about 4000 lives, including that of the great Spanish writer Federico García Lorca, born in Fuente Vaqueros, a town west of Granada. But there were also many victims in republican-controlled areas, in anarchist Málaga around 2500 people were murdered in a month. In response, the Nationalists, with the help of fascists from Italy, executed thousands of Republicans in February 1937. Eastern Andalusia remained in republican hands until the end of the civil war.

At the end of 1936, General Francisco Franco was the undisputed nationalist leader, aided meanwhile by weapons, planes and nearly 100,000 troops from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. The republicans had much less aid, several tens of thousands of French soldiers and many foreigners who fought with the International Brigades. The Nationalists captured Barcelona in January 1939 and Madrid in March of that year. Franco proclaimed himself the winner of the civil war on April 1, 1939.

Andalusia after the Second World War

After the civil war, the bloodshed was far from over, as another 100,000 Spaniards were killed or died in prison. Franco ruled like an absolute monarch, commander of the army and leader of the only political party, the Movimiento Nacional. Spain was spared the Second World War, but suffered a UN boycott after the war, causing the population to suffer from 'anos de hambre' (hunger years) in the late 1940s, especially in poor areas. like Andalusia.

To solve the poor conditions in Andalusia, mass tourism was introduced to the Costa del Sol in the late 1950s. However, this did not prevent approximately 1.5 million Andalusians from looking for work in Madrid, northern Spain and other countries, including the Netherlands, in the 1950s and 1960s. Until the 1970s, many Andalusian villages and towns had no electricity, running water or paved roads, and the education system was very poor. As a result, many of the Andalusians over 50 are still illiterate.

Franco's chosen successor, Prince Juan Carlos, Alfonso XIII's grandson, ascended the Spanish throne in 1975, two days after the death of Franco. The Democratic Party was introduced by Juan Carlos, together with his Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez. A bicameral parliamentary system was introduced and in 1977 political parties and trade unions were again allowed. There was also much more freedom on all kinds of social themes, for example in the field of contraception, homosexuality and divorces. The 1978 constitution makes Spain a parliamentary monarchy with freedom of religion.

In 1982 the Franco era was finally broken when, after free elections, the Partido Socialista Obrero Espanol (PSOE) of Felipe González, a lawyer from Seville, came to power. He remained prime minister for fourteen years and several Andalusians were active in high posts in his party. In 1980 the autonomy of Andalusia approved by referendum and in 1982 Andalusia officially an autonomous region with its own parliament. The first elections to the Andalusian Parliament were won by Rafael Escudero, followed in 1984 by Juan Rodríguez de la Borbolla and in 1990 by Manuel Chaves. In 1986 Spain became a member of the European Union.

Felipe GonzálezPhoto: Claude Truong-Ngoc CC Attribution-Share Alike

Felipe GonzálezPhoto: Claude Truong-Ngoc CC Attribution-Share Alike

Since 1982, the PSOE has also dominated the regional parliament of Andalusia, which is based in Seville. In the eighties and early nineties, the various PSOE parliaments ensured that the economic situation went much better with Andalusia.

Nationally, the PSOE lost power in 1996 to the center-right Partido Popular (PP), which benefited from the economic prosperity in Spain and the rest of Europe for eight years. Andalusia benefited from the growth of tourism and industry, from huge European agricultural subsidies and the construction of houses and offices. Unemployment fell from 32% to 16% during that period, still the highest rate in all of Spain, but a substantial reduction nonetheless.

Andalusia in the 21st century

In the period 2000-2010, hundreds of thousands of job-seeking Eastern Europeans, Africans and Latin Americans emigrated to Andalusia.

In 2004 the PSOE won the national and regional elections in Andalusia, just after the March 11 attacks on trains in Madrid, which killed 191 people and injured 1,800.

In 2006, the Andalusian parliament adopted a new statute, making Andalusia getting more autonomy. This status was approved by referendum in 2007.

In 2008, just before the start of the economic crisis in many parts of Europe, a record number of nearly 10 million tourists visited Andalusia. However, from 2008 to 2012, the crisis hit Andalusia hard, tourism and construction work fell sharply, causing unemployment to rise from 14% to 31%, the highest rate in all of Spain.

In August 2013 announced the then President of Andalusia, JoséAntonio Grinán, on his departure. His successor, Susana Díaz, was elected President of the Andalusian Parliament on September 5, 2013.

Susana Díaz Pacheco, President of the Parliament of AndalusiaPhoto: Juancamartos CC 4.0 International no changes made

Susana Díaz Pacheco, President of the Parliament of AndalusiaPhoto: Juancamartos CC 4.0 International no changes made

Regional elections in March 2015 were held in Andalusia and won by the socialist party PSOE. However, this party again did not achieve an absolute majority, as in the previous regional elections, the PSOE received 47 of the 109 seats in the regional parliament. The conservative Partido Popular, the then national government party, won 33 seats, the worst result in 25 years. The new left party Podemos did remarkably well with 15 seats. In elections in 2018, the balance shifts somewhat more to the right. The far right party Vox comes from nowhere with 12 seats in parliament, the PSOE falls from 47 to 33 seats.

See also the history of Spain on TheWorldOfInfo.

Sources

Andalucía

Lonely Planet

Andalusië

Lannoo

Baird, David / Sevilla & Andalusië

Van Reemst

BBC - Country Profiles

CIA - World Factbook

Dahms, Martin / Andalusië

Van Reemst

Hannigan, Des / Andalusië

Kosmos

Kennedy, Jeffrey / Andalusië & Costa del Sol

Van Reemst

O'Bryan, Linda / Andalusië

Uitgeverij J.H. Gottmer/H.J.W. Becht BV

Wikipedia

Copyright: Team The World of Info