COSTA DEL SOL

History

History

Popular destinations SPAIN

| Andalusia | Catalonia | Costa blanca |

| Costa brava | Costa del sol | El hierro |

| Formentera | Fuerteventura | Gran canaria |

| Ibiza | La gomera | La palma |

| Lanzarote | Mallorca | Menorca |

| Tenerife |

History

The history of Costa del Sol largely coincides with that of Spain described below.

Prehistory

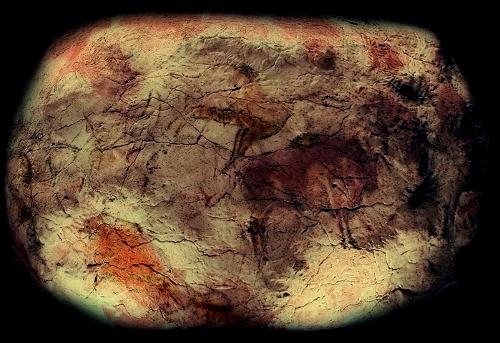

Prehistoric Rock paintings from Altamira, SpainPhoto: Public domain

Prehistoric Rock paintings from Altamira, SpainPhoto: Public domain

Bone splinters found in the Sierra de Atapuerca near Burgos showed that ancestors of the Neanderthals lived in this region 780,000 years ago. The "woman of Gibraltar", a skull of about 50,000 BC, found in 1848, dates back to the Neanderthals. The Neanderthals are thought to be expelled about 40,000 BC, during the last Ice Age by migrants of African origin, the Cro-Magnon people. They hunted mammoths, bison and reindeer. Cave paintings (including Cueva Remigia) with hunting scenes of these people have been found on the east coast. From the beginning of the Neolithic, numerous sites of so-called Impreso objects, including decorated pottery, are found on the east coast of Spain.

In Murcia and Andalusia arose around 3000 BC. the Almeria culture characterized by megalithic tombs and so-called idols or cult statues. Between 3000 and 2000 BC. the use and processing of copper was introduced by the Los Millares - a culture near Almeria. The people of this culture already lived in small walled settlements and already had contacts with communities in southern France, Italy and even northwest Africa.

From around 1600 to 1200 BC. the El Algar culture was found in the southeast of Spain. People lived in walled mountainside settlements and were already in contact with the Egyptian empire and forged weapons and made silver and copper jewelry. At the beginning of the late Bronze Age, this culture suddenly disappeared.

Lady of Elche, Spain 4th century BCPhoto: Carole Raddato CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Lady of Elche, Spain 4th century BCPhoto: Carole Raddato CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

The first Phoenician trading posts originated around 1000 BC. along the south coast, including, in the vicinity of Cádiz, Huelva and Málaga. Approx. 600 BC. they were followed by the Greeks, who founded colonies along the east coast, including Emporion (now: Empúries). The north and west of Spain were then under the influence of Celtic culture. From these three cultures slowly emerged the Iberian culture, in which the Mediterranean characteristics predominate.

The Carthaginian Phoenicians closed in the 7th century BC. the Strait of Gibraltar for Greek navigators and the Phoenician residents of Tire had partially conquered Spain by the end of the 5th century BC. They called the south coast I-shephan-im; Hispania was later created from this name, followed by the current name España.

Carthage, under Hannibal among others, expanded its power over most of Spain, but lost these conquests again in the Punic Wars (First Punic War 264-241 BC; Second Punic War 218-201 BC) with the new strong rising power: Rome. Despite fierce resistance from the Iberians, Spain was conquered by the Romans and at the time of Emperor Augustus, the Iberian Peninsula was divided into three areas: Tarraconensis, Baetica and Lusitania, and these quickly became prosperous areas, partly due to mining. In the 3rd century AD. Prosperity and culture declined sharply, partly due to the raids of barbarians.

The Visigoth Empire (415-711)

Pair of Eagle Fibula, Spain 6th centuryPhoto: Public domain

Pair of Eagle Fibula, Spain 6th centuryPhoto: Public domain

At the beginning of the 5th century, the Roman Empire was so weakened that Germanic tribes such as the Vandals, Alans and Suevi invaded Spain and settled in Galicia, Lusitania and Andalusia. Catalonia was conquered in 415 by the Visigoth king Athaulf, followed by other Gothic conquerors who conquered the entire peninsula in 50 years. Only the Suevi could maintain their independence.

Although the Roman landowners lost a lot of land, the social structure was practically maintained. The cities maintained the Roman organization and the Catholic religion could also be preserved, despite the Visigoths adhering to a different religion. The Visigoth Empire at one point extended to the Pyrenees when the Suevi were also subdued. In the southeast, the Byzantines were expelled.

When Reccared I of the Visigoths converted to Catholicism, all differences between occupiers and native inhabitants disappeared. As a result, the bishops maintained their powerful position, which even extended to the legislature. Not much changed for the ordinary population, they were still exploited by the nobility and the church.

Moorish Spain, the Reconquista and the Catholic Kings (711-1504)

Moorish Alhambra palace in Granada, SpainPhoto: Jebulin in gthe public domain

Moorish Alhambra palace in Granada, SpainPhoto: Jebulin in gthe public domain

The Visigothic era actually ended in 711 when the Moorish soldier Tarik was called to the rescue of conflicts among themselves. By 720 he had conquered the entire peninsula, except for Asturias. Under the Umayyad Dynasty, which lasted from 756 to 1031, a Moorish-Spanish culture developed at a high level.

The city of Córdoba was then the center of this culture, at a time that brought great prosperity and when the arts, literature and sciences flourished. Under the caliphs Abd al-Hahman III and his son Hakam II (period 912 to 976), the Moorish empire was at its peak and Córdoba, for example, had an incredible population of about one million.

From the north, small Christian states such as Navarre, Aragón and Léon threatened the Moorish empire. The general of Hisjam II, Al-Mansur, initially managed to push the Christians far back and destroyed, for example, Santiago de Compostela. In 1002 Al-Mansur died and from then on the Umayyad Empire began to slowly but surely disintegrate into principalities called "taifas".

However, this "reconquista", the reconquest of the Moorish empire by the Christians, was not without a struggle. For example, the important city of Toledo was conquered in 1085 by Alfonso VI of Castile, but in 1086 it was again defeated by the Almoravids led by Ali ibn Yusuf, who came to the aid of their Muslim brothers from North Africa. They managed to restore unity and were succeeded by the Almohads, Berbers from North Africa, who managed to push back the Christians. However, after the Battle of Navas de Tolosa in 1212, Moorish rule was over. Apart from the Moorish kingdom of Granada, southern Spain was conquered by Castile / Leon. However, the Moorish and Christian culture could coexist and develop further because Moors and also Jews retained their rights and freedoms.

In 1469, Catholic Ferdinand II of Aragón and Isabella of Castile married, uniting Spain, although both empires kept their own political structure. Church and state worked closely together from that time, as a result of which the Inquisition and Hermandad (police) suppressed all dissenting opinions and organizations. For example, at the end of the 15th century, more than 120,000 Jews were expelled from Spain for refusing to convert to Christianity.

The Habsburgs (1504-1700)

Charles I of SpainPhoto: Public domein

Charles I of SpainPhoto: Public domein

After the death of Ferdinand and Isabella, Charles I came to power, and had inherited the Burgundian lands from his father Philip the Fair. In addition, he became Emperor of the German Empire in 1519 as Charles V. The discovery of America made Spain the center of the first real world empire, but it was also in constant conflict with France over hegemony in Europe. The wars of religion following the Reformation also affected Spain as a leading country in the Counter-Reformation.

Many Italian possessions meant that Spain effectively controlled the Mediterranean and was obliged to defend itself against the advancing Turks. Inland, there was resistance from the cities and the nobility to non-Spanish politics and the increasing power of the central government. From 1520 to 1521 this led to the revolt of the Comuneros, which was, however, suppressed.

In the meantime, a large colonial empire was built up in America, with which trade was conducted from Seville. This income, in addition to that of the mostly looted gold and silver, went directly to the treasury and not to the development of Spain as a modern country.

Spain's political power in Europe suffered a severe blow during the reign of Philip II. He still conquered Portugal, but lost the battle against the Netherlands, England and Turkey. In Spain itself, supporters of non-Catholic faiths were brutally exterminated and persecuted. Marranos, converted Jews, and Moriscos, Christian Muslims, were particularly affected. For example, in 1609, during the reign of Philip III, about 800,000 Moriscos were expelled from the country. However, this was not a smart move by Philip because it, along with the money-devouring wars, brought Spain to the brink of bankruptcy.

Under Philip IV the economic situation deteriorated even further, because he too plunged into wars with Germany, Italy and France, among others. Extremely high taxes to finance all this led to the exploitation of the own population and a number of revolts in Catalonia, Naples and Andalusia were the logical consequence. In addition, Portugal managed to break free from Spain in 1640, the Northern Netherlands were declared independent in 1648 by the Treaty of Münster and Roussillion had to be ceded to France and Franche-Comté to the Southern Netherlands. At that time, Spain was not a world power any more.

The Bourbons (1700-1868)

Philip V of SpainPhoto:Rijksmuseum in the public domain

Philip V of SpainPhoto:Rijksmuseum in the public domain

After the death of Charles II in 1700, Philip V of Bourbon became king of Spain. Under this king, Spain again lost a lot of territory, such as Gibraltar, Italian territory and the Southern Netherlands, but regained claims to Naples-Sicily and Parma in Italy through his marriage to Elisabeth of Parma. The centralism and absolutism brought by the Bourbons from France led, among other things, to a protracted uprising in Catalonia (1702-1714) and the parliaments of Aragón and Castile were dissolved. Under the enlightened despot Charles III, who ruled from 1759 to 1808, the people again benefited somewhat from increasing prosperity and a reduction in corruption. However, new wars against England ensured that the bad times returned completely under Charles IV and his minister Godoy.

During the French Revolution, Spain first sided with Austria and England (1793-1795), but plunged with the French into a war with England in 1796, which was only briefly interrupted by the Peace of Amiens in 1802-1803. In 1805, Spanish fleet units were defeated at Finistère and Trafalgar. In May 1808, French troops invaded Spain and the king and his son abdicated under pressure from Napoleon. The ensuing popular uprising in Madrid was bloody suppressed by Murat and Napoleon's brother Joseph Bonaparte was made king of Spain.

In response, a bloody nation-wide uprising from 1808 to 1813, supported from Portugal by the British led by Wellington, severely defeated the French at Talavera de la Reina in 1809. In 1812 a constitution on the French model was issued by the "Cortes" in Cadiz.

In May 1813, Joseph Bonaparte left Madrid and on June 21, Wellington's decisive victory over the French followed. The "Cortes" entered Madrid in January 1814 and Ferdinand VII was enthroned after recognizing the new constitution. However, this Ferdinand did not care much about the constitution and soon reigned as an absolute ruler.

During that time, many independence movements also emerged in Spanish America, and many countries broke away from Spain without much difficulty. In the end, only Puerto Rico and Cuba in Spanish America and the Philippines in Asia remained as colonies.

The constitution was restored in 1820 after a military coup (pronunciamiento) by General Riego. An enormous French army, sent by the Holy Alliance, managed to restore absolutism in 1822-1823 and another difficult time for the bourgeoisie followed. The whole of the 19th century was also dominated by the uprisings and civil wars between reactionaries and liberals and the "moderados" between the parties, the moderates, who managed to rule the political scene.

After Ferdinand's death in 1833, he was succeeded by Isabella II under the tutelage of her mother Maria Cristina. Don Carlos, Ferdinand's reactionary brother, started the First Carlist War which lasted until 1839 in northern Spain. Maria Cristina formed a left-wing counterweight to the Vatican-supported Carlists and in 1836 the church's large property was sold by Mendizabel. The moderate politicians and the court developed in a right-wing and a clerical direction after the Carlist War, interrupted only during a liberal interim period from 1854 to 1856, following a successful military coup by O'Donnell.

Revolution and restoration (1868-1923)

Alfonso XIII of SpainPhoto: Public domain

Alfonso XIII of SpainPhoto: Public domain

In 1868, Isabella was deposed and briefly succeeded by General Prim. The Cortes drafted a new constitution and in 1870 elected a new king, Amadeus of Aosta, who came from the Italian royal family. Amadeus of Aosta resigned in 1873 and the "First Republic" was proclaimed which lasted until December 29, 1874. A federal constitution was drawn up and a democratic structure organized.

The newly-baked republic was faced with the Second Carlist War and an uprising with Cartagena as the center. An anarchist movement in the labor movement also caused major problems in agricultural Andalusia and industrial Catalonia. Another military coup or "pronunciamiento" led by General Martínez de Campos soon ended the First Republic and Isabella's son, Alfonso XII, was proclaimed king.

Politically, the period from 1874 to 1923 is known as the "Restoration" and was characterized by alternating liberal and reactionary governments. All of this was based on a relatively liberal 1876 constitution by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo. Cánovas was a so-called "moderado", a moderate politician. These "moderados" made liberals and reactionaries fight for supremacy and largely determined government policy themselves. The people had little to say at the local level in this system. The local and regional rulers were in charge in their area and the influence of the people was minimal. This system was called "caciquismo" and the church also increased its political power.

Cánovas was assassinated in 1897 and the defeat in the Spanish-American War, which also resulted in the loss of the last colonies, plunged Spain into a state of permanent crisis.

Various movements in the political, cultural and nationalist field made themselves heard loudly. Thus the "Generation of '98" aimed for a political and cultural revival and a modern Spain. National movements in the Basque Country and Catalonia became increasingly political and the workers' movement became more and more revolutionary in its actions.

Liberal cabinets, meanwhile, had provided universal suffrage, freedom of trade unions and minimal social legislation in 1890. In practice, however, it all did not amount to much. Internationally, Spain was cast in a bad light after the torture of prisoners in 1896 and the execution by an enraged mob of Francisco Ferrer Guardia, a progressive leader of the rational "modern school". Furthermore, Catalonia and Andalusia were in the negative news due to sometimes bloody social conflicts.

Spain remained neutral in the First World War, with the left strongly sympathizing with the Allies. The right, especially the church, was strongly anti-French. Furthermore, Spain mainly benefited economically through war deliveries. After the First World War, a social revolutionary movement arose throughout Europe, which also afected Spain. The Spanish government responded in 1919 by forcibly repressing a general strike and imprisoning socialist leaders. Later even some well-known members of the trade union movement CNT were killed by police officers. 1923 was an important year. In elections, the socialists first gained ground and the Spanish army suffered a major defeat in Morocco. In the same year on September 13, General Primo de Rivera staged a coup d'état with the knowledge and consent of King Alfonso XIII.

Dictatorship, Second Republic and Civil War (1923-1939)

Primo de Riveira, SpainPhoto: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-09414 CC 3.0 Germanyno changes made

Primo de Riveira, SpainPhoto: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-09414 CC 3.0 Germanyno changes made

Under Primo, Spain became a dictatorship in which the "Cortes" were dissolved, the freedom of the press was abolished and the administration was strongly centralized. From 1929 resistance to this regime increased and in January 1930 Primo resigned and was succeeded by General Berenguer. After the municipal elections of April 1931, all major cities were given a republican administration and that was the sign for Alfons XIII to leave the country, so that Spain quietly became a republic again.

This so-called Second Republic lasted until 1939 and a new constitution was drawn up, this time with a progressive democratic character. Alcalá Zamora became President and Manuel Azaña of the Acción Republicana became Prime Minister. It was important in this period that the separation of church and state was arranged and that education was only given by lay people. Catalonia was also given autonomy with its own government in 1932 and the Basque Country followed in 1936. Abolition of land ownership, military reform and social issues have been slow or not addressed at all. Workers' movements soon alienated from the republic and the logical strikes and anarchist revolts were bloody crushed.

The November 1933 elections were won by the right, but successive right-wing governments did not make much of it, and these two years were called the "bieno negro", two black years. In 1934, a clash ensued between workers' movements and the military in Asturias, which would prove to be the precursor to the later civil war. Many thousands of insurgents went to prison and Catalonia lost its autonomy after it declared independence.

Republican and left parties, united in the Popular Front, won the parliamentary elections in February 1936, and Manuel Azaña became president. The government immediately got into big trouble when the socialists did not want to participate in the government, and a very troubled period followed with strikes and political violence, especially by the Falange, a small but rapidly growing fascist movement.

In the meantime, the right was preparing for a coup. This was deployed by elements of the army on July 17, 1936 from Spanish Morocco. The workers fiercely opposed this and the Spanish Civil War was a fact. The civil war ended on April 1, 1939 with a victory of the "nationalists" of General Francisco Franco Y Bahamonde, who had been the leader of rebel generals since 1936. The sad balance of the civil war left hundreds of thousands of people mistreated, killed or imprisoned.

Franco's Spain (1939-1975)

Franco, SpainPhoto: Public domain

Franco, SpainPhoto: Public domain

Franco was an absolute ruler supported by the only permissible political movement, the right wing Falange, and by the army and the church. So-called "Francoism" wanted only one thing: the revival of Catholic Spain to its former glory and the renunciation of all forces and internal and foreign enemies who had made that former glory disappear. This was not done too gently and affected Catalans, Basques and workers movements, among others.

Socio-economic life was dominated by vertically organized syndicates following the fascist-corporate model, but for a long time caused poverty, hunger, corruption (black market), economic stagnation and cynicism. Economically, Spain did not return to the level of 1936 until 1956. All illegal organizations and exiles could not seriously threaten the regime.

In World War II, Franco supported Germany and Italy, to whom he partly owed his victory in the Spanish Civil War. Spain itself did not become a war zone; a volunteer army, the Blue Division, did take part in the fight against the Soviet Union.

In 1943 he appointed the monarchist Jordana as minister of foreign affairs and in 1947 he formally restored the monarchy without appointing a king. After 1945, Spain became isolated and the Franco regime was condemned by the United Nations. It was not until the mid-1950s that Spain emerged from this isolation by joining the United Nations in 1955 and the OEEC, the Organization for European Economic Cooperation, the predecessor of the OECD in 1959. From 1953 onwards things went better economically due to a number of economic treaties with the United States. The Spanish colonies of Morocco, Spanish Guinea (now: Equatorial Guinea) and Spanish Sahara (now: Western Sahara) were abandoned in 1956, 1968 and 1975 respectively. Alfons XIII's grandson, Juan Carlos de Bourbon, was appointed by Franco as his successor in 1969. Juan Carlos was even brought up under Franco's supervision.

In the 1960s, Spanish society changed due to an influx of foreign capital, the rise of tourism and the Spanish migrant workers who brought home a lot of money. As a result of all these developments, industrialization and urbanization increased sharply and the economy grew well. With modernization, the influence of the Falange and the syndicate system became less and less important.

Within the regime of Franco there was also an increasing effort to liberalize the system. For example, the modernist Roman Catholic lay organization Opus Dei occupied important economic government posts and new opposition movements were set up. In Catalonia nationalism revived and in the Basque Country a new liberation movement, the ETA, started an armed struggle with the established order. Many terror attacks were to follow and the regime was very tough on ETA and other terror groups.

In 1973, Prime Minister Carrero Blanco, the regime's second man behind Franco, was killed in an attack by ETA, and on November 20, 1975, dictator Franco himself died.

Spain becomes a parliamentary democracy

Proclamation and swearing-in of Prince Juan Carlos as King of SpainPhoto: Nationaal archief in the public domain

Proclamation and swearing-in of Prince Juan Carlos as King of SpainPhoto: Nationaal archief in the public domain

On November 22, 1975, King Juan Carlos was sworn in. To everyone's surprise, he immediately paved the way to a parliamentary democracy that was achieved by legal means through a number of referendums. Franco's last prime minister, Arias Navarro, was succeeded by Adolfo Juarez who started the period of transition ("transición). All civil liberties were allowed again, exiles returned and banned parties such as the socialist and the communist were legalized.

In 1977, free parliamentary elections were held for the first time since 1936 and were won by the UcdD, Union of the Democratic Center, led by Prime Minister Suarez. The second party was the PSOE led by Felipe González.

The new 1978 constitution officially made Spain a parliamentary democracy. The 1979 elections were also won by the Juarez party, and in the early 1980s Catalonia and the Basque Country became autonomous first, followed by all other regions. However, the ETA of the Basque Country wanted more and reinforced that with more attacks. In the army, too, there were certain elements against the further democratization. On February 23, 1981, an attempted military coup led by a colonel of the Guardia Civil, Tejero, followed. The attempt failed because King Juan Carlos, as commander in chief of the armed forces, strongly opposed this coup attempt.

The period Felipe González

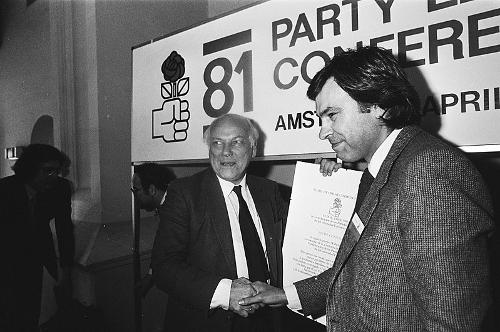

Felipe González, Spain meets Joop den UYl, The NetherlandsPhoto: Hans van Dijk / Anefo in the public domain

Felipe González, Spain meets Joop den UYl, The NetherlandsPhoto: Hans van Dijk / Anefo in the public domain

Just before the coup attempt took place, Suarez had been succeeded by L. Calvo Sotelo. The 1982 parliamentary election was won by the PSOE and the right-wing alliance now became the main opposition party. Felipe González became the new prime minister and although his first term was ravaged by corruption scandals, he also won the 1986 and 1990 elections. The expected process of renewal and the reduction of unemployment failed to materialize under his rule. After a referendum, Spain joined NATO in 1982 and the European Community in 1986.

In 1992, 500 years after Columbus' discovery of the Americas, Spain was in the spotlight worldwide through the Olympic Games held in Barcelona and the World's Fair held in Seville. In 1992 and 1993, several important ETA leaders were arrested and the Basque population increasingly turned away from the terrorist organization. The González government, meanwhile, faced increasing difficulties due to financial and political scandals and could only continue to rule with the support of Basque and Catalan nationalists who demanded even more autonomy in return.

Municipal and provincial elections were held in May 1995 and were won by the conservative People's Party (PP) of opposition leader José María Aznar. In December, the Secretary of State, Javier Solana, was appointed Secretary General of NATO. Early elections in March 1996 for both houses were just won by the PP for the PSOE. There was a minority government headed by Prime Minister Aznar, which was based on an alliance with Basque and Catalan parties together with the Canary Islands coalition. Again, this alliance was established after promises for more autonomy.

The period Aznar

Aznar, SpainPhoto: Kremlin.ru CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Aznar, SpainPhoto: Kremlin.ru CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

The economic policy of the Aznar government was aimed at stable economic growth and they wanted to meet the conditions for joining the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). Cutbacks and privatizations made it possible to meet the conditions. Economic growth in 1998 was 3.5% and inflation remained consistently low at 2.4%. Spain was therefore admitted to EMU on 1 January. The only thing that the Aznar government failed to do was reduce the high unemployment rate.

ETA meanwhile carried out more and more attacks despite massive demonstrations against political violence. The conviction of 23 leaders of Herri Batasuna (HB), the political arm of ETA, led to new clashes at the end of 1997 between the supporters and opponents of Basque independence.

In early 1998, demonstrations against the verdict followed in several Basque cities, and attacks against local PP politicians were intensified. One problem was that the various political parties did not agree on the strategy with regard to ETA. The Basque Partido Nacionalista Vasco (PNV) maintained the view that only negotiations with Herri Batasuna could lead to success. However, the PP and the PSOE disagreed and the Aznar government opted for the hard line. In March 1998, another eight ETA members of the notorious Arab Command were arrested and a few months later the Basque newspaper Egin was banned and the related radio station Egin-Irratia was taken off the air. Following the so-called "Irish consultation", the nationalist Basque parties were able to persuade ETA to institute an armistice for the partial elections in the Basque Country, which were to take place on 25 October. The PP and PSOE made surprisingly small gains, but the nationalist parties still gained a majority. Direct negotiations with ETA were announced by the Aznar government in November.

In 1997, González was again discredited for his alleged involvement in a number of corruption cases and illegal activities. In June 1997 he stepped down as party leader and was temporarily replaced by the ex-minister Joaquín Almunia. In April 1998, the ex-Minister of Public Works, José Borelli, became the new party leader of the PSOE.

Later that year, politicians from the ruling PP made negative headlines over corruption allegations, and Spain joined NATO in December. These new cases of corruption embarrassed the Aznar government for pledging to end the corruption practices.

In the last years of the 20th century, the question surrounding the English enclave of Gibraltar came back to the corner. The Aznar government proposed that after a transition period of 100 years, during which Gibraltar would come under Spanish-British rule, the colony should be transferred to Spain.

In March 1999 tensions arised again between Great Britain and Spain because of Gibraltar. Spain accused Britain of insufficiently supervising organized crime, which would have turned Gibraltar into a haven for criminals. However, Britain denied everything, claiming that the allegations were intended to bolster Spain's claim to Gibraltar. Spain responded with tighter border controls. The ceasefire with ETA announced in 1998 was unilaterally terminated by ETA at the end of 1999.

Internationally, Spain came to the fore with the international arrest warrant for the Chilean ex-dictator Pinochet, issued by Spanish judge Baltazar Garzón. On October 16, 1998, Pinochet was arrested in London.

In March 2000, Aznar's party won a major electoral victory and the PSOE suffered its worst defeat in more than twenty years. In April Aznar formed a new cabinet, in which many ministers remained in the same post.

The period Zapatero

Zapatero, SpainPhoto: Monika Flueckiger CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Zapatero, SpainPhoto: Monika Flueckiger CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Since the elections of 14 March 2004, the socialist party 'PSOE' has taken office as the governing party with José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero as MP. Elections were held three days after the Madrid bombings (March 11). Compared to the policies of the previous Aznar government, the MP-Zapatero government is more focused on social-democratic themes: raising the minimum wage and basic pension, legislation against domestic violence and gender discrimination, and reform of the rules on divorce. The most notable reform is the introduction of same-sex marriage on June 30, 2005. Zapatero also wins the parliamentary elections in March 2008 and will form a new cabinet in April that for the first time has more women than men. In January 2009, Spain was hit hard by the economic crisis and went into recession for the first time since 1993. In March 2009, the unemployment rate has grown to a record high of 17.4% of the labor force. In March 2010, unemployment will even rise to over 20%.

Social unrest and strikes break out as a result of the government's cutbacks due to the credit crisis. In May 2010, parliament approved a 15 billion euro austerity package.

The period Rajoy

Rajoy, SpainPhoto: European People's Party CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Rajoy, SpainPhoto: European People's Party CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

The Conservative party wins the elections in November 2011. A month later, the new government, led by Mariano Rajoy, takes office. In the summer of 2012, the unemployment rate will rise to over 25% and Spain will have to ask for help from the EU. In the autumn of 2012, the banking crisis hit hard and the government created so-called "bad banks" at the request of the EU to stop bad loans. In 2013, Spain was ravaged by corruption scandals involving the Royal House. Economically, Spain is progressing and in September 2013 there is a slight growth of 0.1%. This development appears to be continuing at the beginning of 2014.

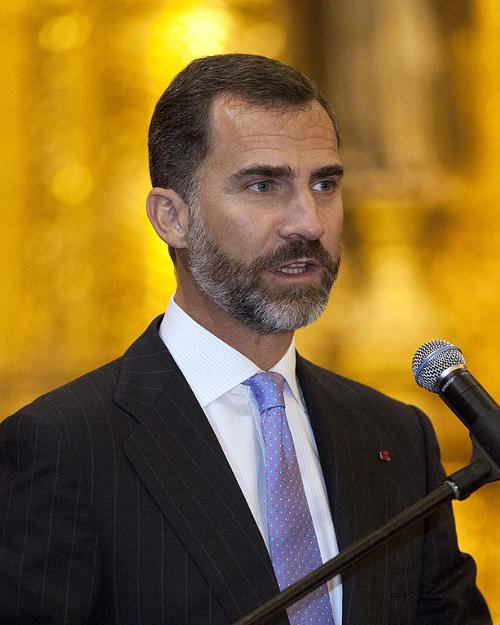

King Felipe VI of SainPhoto: Cancillería Ecuador CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

King Felipe VI of SainPhoto: Cancillería Ecuador CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

In May 2014, Prime Minister Rajoy announced the resignation of King Juan Carlos. On June 19, 2014, he will be succeeded as head of state by his son Felipe VI. In May 2015, Podemos, the anti-austerity party, wins big in regional and local elections. In June 2016, the Conservatives win in a repeated parliamentary election, but fall short of seats for an absolute majority. Spain is in an impasse because the country is not used to a coalition government. Rajoy claims he wants to form a new government. In October 2016 he succeeds because the socialists abstained from voting in the formation of a minority cabinet. In March 2017, the former Catalan president Artus Mas is banned from declaring a public office for civil disobedience around the refrendum on Catalonia's independence. In August 2017 there is a major terrorist attack on the Rambla in Barcelona. In September 2017, Rajoy's Spanish government appealed the referendum on the secession of Catalonia. The Spanish Constitutional Court has called the referendum illegal. In October 2017, the referendum will be held and the Spanish police will intervene hard. The majority of the population supports the Seperatists and the Catalan government declares independence. Puigdemont leaves for Brussels and an arrest warrant is issued against him. In December 2017, the Spanish government is organizing elections in the hope that the majority will now vote for Spain. The pro-Spanish party is becoming the largest, but the majority of the population unexpectedly supports seperatist movements. There is a stalemate. In 2018 Eta announces rhat it will cease all political activities, Rajay looses a vote of confidence. Socialist leader Pedro Sánchez becomes prime minister

The period Sánchez

Sanchez, SpainPhoto: European Parliament CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Sanchez, SpainPhoto: European Parliament CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

In 2019 several election are held. The socialists are on the winning hand but fail to reach an absolute majority, but in January 2020 Pedro Sánchez wins a narrow parliamentary vote of confidence and he forma a minority government with left wing Podemos party.

Sources

theworldofinfo.com/spain

Wikipedia

Oosterman, I / Costa Del Sol, Andalusië

CIA - World Factbook

BBC - Country Profiles

Copyright: Team The World of Info