BRITISH COLUMBIA

Population

Population

Popular destinations CANADA

| Alberta | British columbia | Manitoba |

| New brunswick | Newfoundland and labrador | Northwest territories |

| Nova scotia | Nunavut | Ontario |

| Prince edward island | Quebec | Saskatchwan |

| Yukon |

Population

General

Vancouver people flock to the Stanley Cup ice hockey finalPhoto: Vaska037 CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Vancouver people flock to the Stanley Cup ice hockey finalPhoto: Vaska037 CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

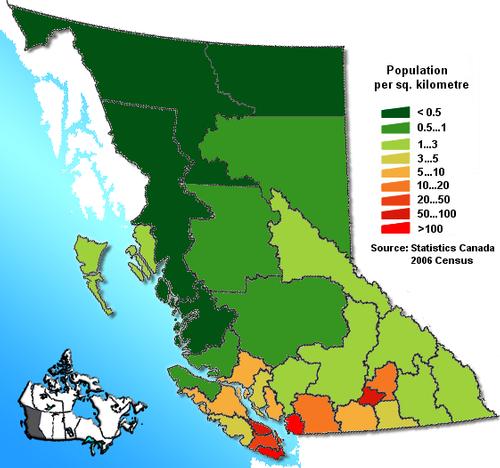

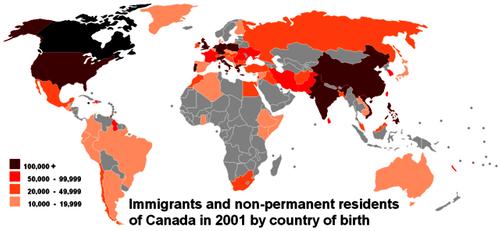

Canada is a country of immigrants, just like British Columbia. The provincial population was 178,000 in 1901, grew to 1.1 million at the end of the Second World War and due to continuous immigration flows to approximately 5,6 million in 2017. Although the largest group of immigrants comes from the British Isles, there are also large groups Germans, Italians, Russians, Ukrainians and Greeks. More recent are Asian immigrants, for example from Hong Kong after it joined China. Due to its location on the Pacific Ocean, Vancouver has many Chinese, more than 100,000, and other Asian immigrants. Today, about half of the population is of Asian descent and after Chinatown San Francisco and Chinatown Manhattan New York, Vancouver has the largest Chinatown in North America. Chinatown in the capital Victoria is the oldest Chinese neighborhood in Canada and the entire North American west coast, because it dates back to the 1970s. In 2006, British Columbia counted more than 30 ethnic groups of more than 20,000 inhabitants following a census.

British Columbia joined Canada in 1871 as the sixth province. It is known that about 90% of the Canadian population lives within 100 miles of the United States border. Less well known is that about 75% of the British Columbian population lives within 60 km of the Atlantic coast. The city of Vancouver has just over 680,000 inhabitants, in the metropolitan area, with suburbs such as Surrey, Burnaby, Richmond, Coquitlam, Maple Ridge, New Westminster, Port Coquitlam, North Vancouver, Port Moody, White Rock, Pitt Meadows and Langley , live about 2.5 million people.

About 760,000 people live on Vancouver Island, of which more than half live in the southern conurbation of Victoria, which has a very pleasant climate. The rest of the people live on the southeast coast and some villages in the west and north of the island. Nanaimo is the second largest city on Vancouver Island with approximately 85,000 after Victoria.

British Columbia Population Density OverviewPhoto: Public domain

British Columbia Population Density OverviewPhoto: Public domain

Dutch Canadians

Although the first Dutch arrived in North America as early as the 17th century, the flow only really got going during the American Revolution (1775-1783), when Dutch Loyalists settled in the British North American colonies. This group adapted quickly and became part of the large wave of immigration after 1815. From about 1850, poor economic and social conditions in the Netherlands caused a large wave of immigration to start again, which mainly concentrated on the American 'frontier'. From about 1880 the cheap agricultural land became more and more expensive and new immigrants and American Dutch people moved to the Canada 'Last Best West'.

A population survey in 2006 showed that there are just over one million Canadians with a Dutch background. The emigration of Dutch people to Canada can be divided into three periods. During the first period from 1890 to 1914, Dutch immigrants moved to the prairies of western Canada and established settlements such as New Nijverdal (now Monarch in Alberta), Neerlandia in Alberta (1911) and Edam in Saskatchewan (1907).

Edam Cafe in Edam, SaskatchewanPhoto: Jacobsimmonds CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Edam Cafe in Edam, SaskatchewanPhoto: Jacobsimmonds CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

The majority of these immigrants spread across western Canada as farmers or farmhands. Other immigrants settled around major cities like Calgary, Edmonton and Winnipeg. The latter city probably had the largest Dutch community in Canada before the First World War.

The second major wave of immigration lasted from 1923 to 1930, ending at the beginning of the Great Depression. There was not much cheap farmland left, but in other sectors it was still easy for immigrants to find work, especially after the economic crisis came to an end and the economy started to recover. Especially in Ontario and western provinces such as British Columbia, the Dutch immigrants seized their opportunity. During that period, many Dutch people settled in the south and southwest of Ontario, especially in Toronto. It is estimated that approximately 25,000 Dutch and American-Dutch immigrants settled in Canada between 1890 and 1930.

Immigration to Canada briefly dropped due to the great economic crisis in the 1930s and the Second World War, but from 1947 onwards, immigration from economically ruined countries in Europe started again. Initially, the new immigrants again mostly came from the agricultural sector, but soon more technicians and other professionals were needed. Ontario was the most popular destination, but many immigrants also moved to Alberta, British Columbia and the maritime provinces. By the end of the 1960s, approximately 150,000 Dutch immigrants had settled in all Canadian provinces, except Newfoundland & Labrador.

Overview of the number of immigrants, +100,000 from the NetherlandsPhoto: Kransky CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Overview of the number of immigrants, +100,000 from the NetherlandsPhoto: Kransky CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

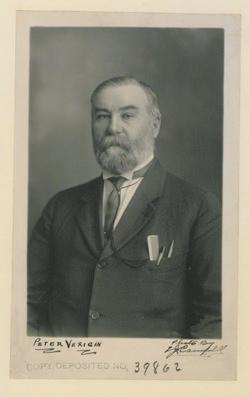

Special are the many descendants of 19th century Russian immigrants, initially in the province of Saskatchewan, in towns such as Grand Forks and especially Castlegar (since 1908), but also in the province of Saskatchewan. These so-called 'Duchoboren', religious pacifists from southern Russia and Ukraine, fled in 1899 because of their religious-political convictions under the leadership of Peter Verigin (1859-1924) or 'Lordly' from Russia before the Russian Tsar Nicholas II to Canada, among other places. . They disregarded the government and rejected the liturgy and procedures of the organized church. They believed that God resided in every individual, not in a church building or institution. The Douchoboren were supported, among others, by the famous Russian writer Leo Tolstoy. In the 1920s, there were approximately 90 shower-bore settlements in British Columbia, each with about sixty residents. There are currently about 15,000 Douchobors living in British Columbia, about 30,000 if everyone with Douchobor roots is included. The 'Freedomites' or 'Sons of Freedom' were a controversial split sect that did not shy away from violence and often walked around naked.

Peter Verigin, leader of the DouchoborenPhoto: E.J. Campbell / British Library in the public domain

Peter Verigin, leader of the DouchoborenPhoto: E.J. Campbell / British Library in the public domain

First Nations

British Columbia's lush coast has attracted many cultures over the past thousands of years. Due to the massive presence of food (including salmon), peoples such as the Haida, Nuxalk and Tsimshian had enough time to make beautiful totem poles and large canoes. In the interior of British Columbia the situation was completely different for a people like the Salish, where life was mainly focused on the basic necessities of life and surviving the long and harsh winters. In the far north, peoples like the Tagish and Gwich'in were completely dependent on migrating elk and reindeer. The largest indigenous group are the Quw'utsun, of whom approximately 4,000 people live in the Cowichan Valley.

The decline of the First Nations began with the arrival of The Europeans and their diseases. Later on, issues such as racism and pure discrimination were added. As late as 1859, British Columbia's Governor James Douglas decreed that all the land and property of the First Nations peoples belonged to the Crown. The age-old potlatch tradition was also banned. From the second half of the 20th century, the various (national) governments reconsidered all these decisions and the culture of the First Nations was again valued and promoted more. A difficult and complex process is the claims of the First Nations to their pre-1859 land possessions. To date, one agreement has been made, namely with the Nisga'a people, who received compensation of $200 million and a certain amount of of self-government. Only 20% of all First Nations peoples have started negotiations.

In British Columbia, a 'Recognition and Reconciliation Act' was passed in 2009 that literally scrutinizes all laws related to the First Nations. One of the ideas is to unite the 203 First Nation peoples of British Columbia under about 30 governing bodies. But as early as 2011, a summit of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs and the British Columbia Assembly of First Nations concluded that the law was unenforceable and was effectively declared "dead."

Flag of the Nisga'a people, British ColumbiaPhoto: Public domain

Flag of the Nisga'a people, British ColumbiaPhoto: Public domain

Potlatch

The original inhabitants of British Columbia all celebrated the so-called 'potlatch' ceremony in honor of special events. For several days there is dancing, fasting and the exchange of gifts. The invited guests are expected to throw a thanksgiving party a while later. That party is often even more beautiful and bigger than the original party. The guests at this party are also more or less obliged to hold another thanksgiving party. This cycle can last for months. The potlatch was banned in 1927, but has been legal again since 1951 and is still celebrated today.

Totem Poles

The First Nations totem poles on the coast of British Columbia are the highlights of many a tourist. The totem poles had and have various functions, from portraying stories to explaining family history. Scientists assume that totem poles were already used before Europeans came into contact with First Nations, but often as part of a home. It wasn't until the 19th century, using much better materials, that totem pole making fully blossomed. This development was almost brought to an end by the cultural repression exerted on the First Nations by the Canadian and American authorities.

It was not until the 1930s that the making of totem poles was taken up again by woodcarvers such as Mungo Martin, a Kwakwaka'wakw chief who made many totem poles for the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria. At the end of the 20th century, the totem poles became known worldwide again by the Haida artist Bill Reid.

Totem poles are sacred to the First Nations and the designs belong specifically to a family, clan or group. Many First Nations are trying to retrieve ancient totem poles from the 19th century from the various museums where they are exhibited worldwide.

Totem poles are almost always made from the 'Western red cedar', the giant tree of life. The largest totem pole in the world is the two-piece, 53-meter high totem pole in Alert Bay in northern Vancouver Island. The area around the Hazeltons, Old Hazelton, South Hazelton and New Hazelton, is known as the Totem Pole Capital of the World.

Tallest totem pole in the world in Alert Bay, British ColumbiaPhoto: Owen Lloyd CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Ogopogo

British Columbia has its own Loch Ness Monster, Ogopogo. Ogopogo has a dragon-like appearance and according to the Salish First Nation lives in Lake Okanagan in southern British Columbia and can be seen throughout the Okanagan Valley on postcards, billboards or bumper stickers. The name Ogopogo comes from a song that was often heard in the variety theaters in the 1920s, but the myth dates back much earlier. The Salish believed in a creature called N'ha-a-itk, meaning "more-demon," a demonized man who had been punished by the gods for allegedly killing a fellow tribesman. To please the monster, the Salish sacrificed animals every time they got close to Rattlesnake Island, where Ogopogo resided.

Ogopogo, Okanagan Lake, British ColumbiaPhoto: Hamedog / Beyond My Ken CC3.0 Unportedno changes made

Ogopogo, Okanagan Lake, British ColumbiaPhoto: Hamedog / Beyond My Ken CC3.0 Unportedno changes made

Sources

BBC - Country Profiles

British Columbia and the Rockies

Michelin Apa Publications

Canada

Cambium

Canada

Lonely Planet

CIA - World Factbook

Elmar Landeninformatie

Jepson, Tim / Vancouver en de Canadese Rockies

Wat & Hoe

Leigh Fleming, Janet / British Columbia : a walking guide

Cicerone

Ohlhoff, Kurt Jochen / Canada west & Alaska

ANWB

Phenix, Penny / Canada

Wat & Hoe

The rough guide to Canada

Rough Guides

Struijk, Aad / West-Canada

Elmar

Veldt, Marc / Canada

Gottmer/Becht

Ver Berkmoes, Ryan / British Columbia & the Yukon

Lonely Planet

Wagner, Heike / West-Canada : Alberta, British Columbia

Lannoo

Wikipedia

Last updated June 2025Copyright: Team The World of Info