SLOVENIA

History

History

Cities in SLOVENIA

| Ljubljana |

History

Antiquity and Early Middle Ages

Bronze Situla from the Halstatt period, SloveniaPhoto: Joanbanjo CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Bronze Situla from the Halstatt period, SloveniaPhoto: Joanbanjo CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Human settlement already existed in the Old Stone Age, but unfortunately few remains from this period have been found. Many remains from the Neolithic era have been found, including remains of settlements of stilt houses near the capital Ljubljana. Much has also been preserved from the so-called Central European Hallstatt period (10th-4th century BC).

The oldest known inhabitants of the Slovenian territory were Celts and Illyrians who lived in the 4th century BC. moved into the eastern Alpine region. The Celts called this area Noricum, after the most important tribe of that time. In the 2nd century BC. there was a lot of trade between the Romans and the Celts, who also took over more and more of the Roman culture. Finally, in 10 BC. Noricum was incorporated into the Roman Empire without any struggle and all the conquered territories were divided into provinces, one of which was Histria (now: Istria).

The main Slovenian settlement became Emona, now Ljubljana. In the 3rd century AD. the Roman Empire was threatened by Germanic tribes and an extensive defense system was built (Claustra Alpinum Juliarum). That didn't really help because in the 5th century the Western Goths entered Italy, followed by the Huns and the Eastern Goths. These Eastern Goths also occupied Slovenian territory as well as the Lombards in the mid-6th century.

Middle Ages

In 500 AD. the great migration of the population starts and Slavic and Germanic tribes leave a devastating trail through Europe. In the 6th century, West Slavic tribes from the Eastern Alps, the ancestors of today's Slovenes, settled in this area. The Slavic principality of Karantanija was created around 620, encompassing large parts of present-day Austria and Slovenia. In the 8th century, the Slovenes were threatened by the advancing Avars and sought support from the Duchy of Bavaria.

Karantanija around 990, SloveniaPhoto: Bostjan 46 CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Karantanija around 990, SloveniaPhoto: Bostjan 46 CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In 788 Slovenia became a Frankish province in the empire of Emperor Charlemagne. Between 869 and 874, the country, then called Carniola, regained its independence and Prince Kocelj introduced the Slavic script and the liturgy in the vernacular. In the 9th century Slovenia was Christianized by missionaries from Salzburg, Austria, and many German settlers arrived along with these clergy. In the second half of the 9th century, the Frankish Empire was threatened by the Hungarians, but the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 was lost by the Hungarians. In 963 Slovenia's predecessors, Karantanija and Carniola, became part of the Holy Roman Empire and divided into so-called “marks” or border regions. In the Middle Ages, these border regions developed under the leadership of feudal rulers into fairly independent provinces, with Carinthia as the most important province. In the 11th century Carinthia dominated all other regions, but in the first half of the 12th century this domination came to an end. During this time the Bohemian king Ottokar Premsyl II conquered large parts of the border regions, but these were subsequently reclaimed by the Habsburg emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Rudolf I. In 1278 the Battle of Dürnkrut was won by Rudolf and Ottokar was killed in the battle. battlefield. Since 1282, almost all Slovenian areas have been part of the Habsburg Monarchy.

Sixteenth to nineteenth century

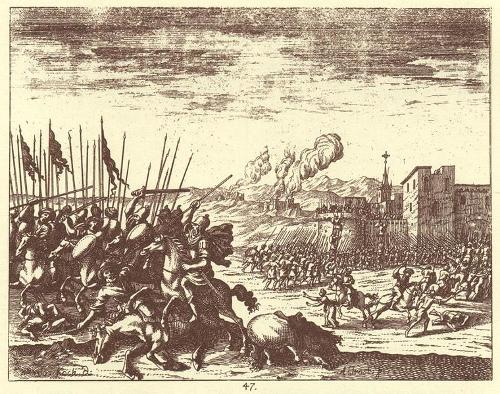

Turks and Habsburgs fight in Slovenian territory, 1689Photo: Public domain

Turks and Habsburgs fight in Slovenian territory, 1689Photo: Public domain

Yet in the Slovenian territories there was always a longing for independence and freedom. In the 15th century, for example, the Counts of Celje tried to realize this goal, but after a political assassination in 1456, this attempt failed. After this Protestantism gave rise to new nationalist feelings and in 1551 a catechism and a language book in Slovenian were published, followed by a Bible translation in 1584. However, the Counter-Reformation suppressed Protestantism and practically disappeared completely.

From the sixteenth to the early eighteenth century (1515-1713), the peasants regularly revolted and demanded more freedom and political participation, again without result. Furthermore, the Slovenes were regularly threatened by the Turks, but they did not get further than the south of the country. In the early 18th century, the Habsburg Monarchy went to war with Spain and the Hungarians. This gave the Habsburgs more access to the Adriatic Sea and Trieste and Rijeka were declared free ports. Economic good times dawned for the Slovenian areas and a Slovenian middle class with a renewed Slovenian self-awareness emerged.

The French Revolution strongly promoted the national feeling again and in 1788 the first history book about Slovenia was published and the first nationalist poets made themselves heard. From 1805, the French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte managed to occupy almost the entire Slovenian territory. He created the Illyrian provinces in 1809 by connecting a number of Croatian and Slovenian regions. After the defeat at Waterloo in 1813, the Illyrian provinces were cleared by the French and taken over by the Austrians.

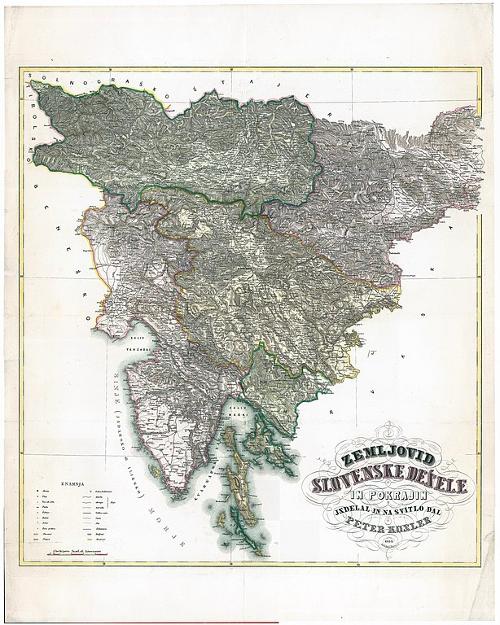

Map of Slovenia from 1852Photo: Public domain

Map of Slovenia from 1852Photo: Public domain

In 1848 the absolute regime of Metternich was pushed aside in Austria and this was the signal for the Slovenian peasants to revolt against the feudal rulers. The revolt was a great success and in September 1848 the feudal system was finally abolished by imperial manifesto. The enlightenment and the rise of liberalism also ensured the further development of Slovenian national consciousness. Political consciousness even arose, and a political program was drawn up by liberals and nationalists for a united Slovenia. For the time being, however, this autonomy movement did not get a hold of the Austrian rulers, who were strongly influenced by the German inhabitants of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

In 1866 the Habsburgs were defeated by the Prussians and a so-called double monarchy, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was created. Ideas surrounding "trialism" arose in the upper Slovenian circles. This new state vision arose due to the threat of ever-increasing Germanic region of Slovenia. The "trialists" proposed an alliance with the Croats (Illyrian movement) in order to create a third unit (also together with Bosnia-Hercegovina) in the Habsburg empire. However, the majority of the Slovenian population was not enthusiastic about this idea.

World War I, Interwar and World War II

Alexander Karadjorjevic, SloveniaPhoto: Public domain

Alexander Karadjorjevic, SloveniaPhoto: Public domain

In 1914 World War I broke out and the Slovenes fought with the Habsburg (German) armies. After the First World War, a lot changed in Europe. In Slovenia, the trialist idea became more popular again, and in 1917 South Slavic delegates in the Vienna parliament demanded the unification of Slovenia, Croatia, Vojvodina, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Dalmatia (Serbia was added later). They declared that they wanted an independent South Slavic state. After the war, the Habsburg Empire disintegrated into the republics of Hungary and Austria, creating the so much desired independent "Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes". On December 1, 1918, Alexander Karadjorjevic was proclaimed king and the Kingdom was expanded to include Kosovo, Macedonia and Montenegro.

That this artificial land would collapse completely was almost inevitable. From the beginning, things did not go well between the Serbs and the Croats due to fundamental differences in matters such as mentality, religion and vision of the future. For example, Croatia wanted a federative state while the Serbs were only interested in increasing their power. In 1929 the constitution was abolished and a royal dictatorship was created. King Alexander changed the name to Yugoslavia (officially: Yugoslavia = South Slavia) and the Serbs became the dominant population group. They ruled both in the civil service and in the army. Until 1941, there was only one non-Serbian prime minister, the Slovenian Anton Korošec, who, however, only lasted half a year. The 1930s were very turbulent economically and politically and King Alexander was killed in an attack in 1934.

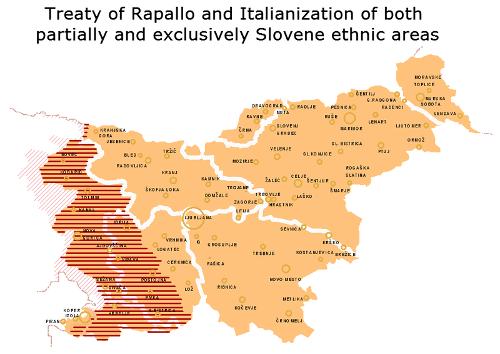

Italian occupation of SloveniaPhoto: DancingPhilosopher CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Italian occupation of SloveniaPhoto: DancingPhilosopher CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Yugoslavia was involved in World War II on April 6, 1941. Despite the fact that Yugoslavia had joined Germany and Italy, the Germans invaded Yugoslavia and bombed Belgrade. On April 17, the Yugoslav army surrendered unconditionally. Hitler then divided Yugoslavia, with the Germans occupying northern Slovenia and Italy occupying west and southwest Slovenia. Croatia became a fascist state and other parts of Yugoslavia went to Albania, Bulgaria and Hungary, which took care of the Slovenian Prekmurje.

Croatia meanwhile indulged in unprecedented atrocities against Serb minorities, fueling hatred between the two peoples. Two major resistance movements arose under the Serbs, the Cetniks and the Partisans. The cetniks wanted the old kingdom back, dominated of course by the Serbs. The communist partisans led by the Croat Josip Broz (Tito) saw more in a federal Yugoslavia and managed to organize a large multi-ethnic resistance movement, the National Liberation Front. The Slovenes also took part in this Liberation Front, which fought not only the Italians and the Germans but also the anti-communist cetniks. The Liberation Front emerged victorious and liberated Belgrade together with the Russians in October 1944. On May 8, 1945, the Germans surrendered and Yugoslavia suffered about one million deaths.

A great human drama also took place after the war. Tens of thousands of refugees, cetniks, ustašas and other anti-communists tried to join the Allies, but they turned them over to the partisans. Tito's partisans subsequently murdered tens of thousands of anti-communists and there was also a huge massacre of the Hungarians in Vojvodina.

Period Tito

Tito, SloveniaPhoto: Stevan Kragujevic CC 3.0 Serbia no changes made

Tito, SloveniaPhoto: Stevan Kragujevic CC 3.0 Serbia no changes made

Tito was thus the mighty man in post-war Yugoslavia and he aspired to a federal Yugoslavia under the leadership of the communist party. In November 1945 the time had come and the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia was proclaimed, which consisted of the republics of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Slovenia. Serbia also had the autonomous regions of Vojvodina and Kosovo.

At that time, Yugoslavia was a state with central authority in Belgrade and republics that only had something to say on paper. Attempts by the Soviet leader Stalin to bring Yugoslavia fully under the Soviet sphere of influence met with much resistance from Tito and his followers, and in 1948 there was a split between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. Tito was also the one who founded the Movement of the Non-Aligned with, among others, Nehru of India and Nasser of Egypt.

In the 1960s, however, a federal state structure slowly developed with more freedom for business. Despite this, unemployment rose sharply and many Yugoslavs moved to Western Europe as guest workers. In the second half of the sixties, the party decided on far-reaching political decentralization, whereby the power was largely transferred to the communist party branches of the republics. This was an attempt by Tito to rein in ethnic divisions and the associated nationalism. Yet more and more frictions arose between the different republics and population groups. For example, the call for secession and independence in Croatia grew stronger in the early 1970s. Tito reacted harshly to this with purges among the intellectuals.

In 1980 Tito died, leaving behind a country with screeching inflation, a large national debt, mass unemployment and a large part of the population living in poverty. And furthermore, the unstable society consisting of more than 15 ethnic groups was still a fuse of which only the fuse had to be lit.

In 1981 student riots broke out in Priština, the capital of Kosovo. Security forces restored order at the cost of an unknown number of deaths, but this was the beginning of much of the misery to follow. The Serbs took advantage of this event and in 1986 a memorandum was published by a number of Serbian artists and scholars. This memorandum included warning of all "enemies" who threatened Serbia and that it was high time for a Greater Serbia to avert that disaster.

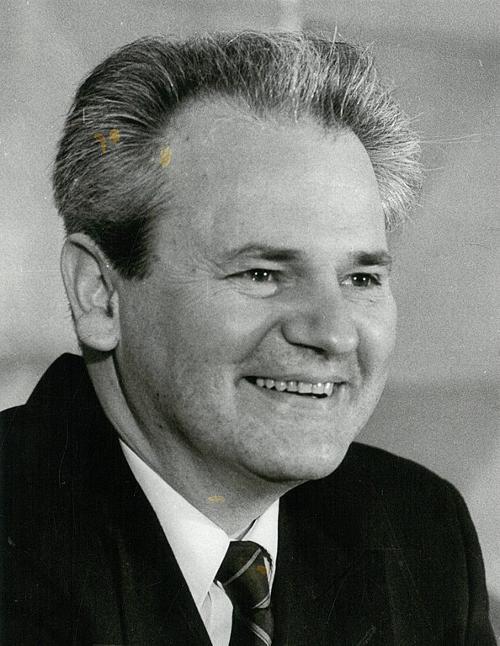

Period Miloševic

Slobodan Miloševic, SloveniaPhoto: Stevan Kragujevic CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Slobodan Miloševic, SloveniaPhoto: Stevan Kragujevic CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In May 1986, Montenegrin Slobodan Miloševic became Chairman of the Serbian National Committee, which of course fully supported the ideas of the Memorandum. In 1987 President Stambolic was put aside by Miloševic, who thus took all power. In October 1988, the autonomy of Vojvodina and Kosovo was ended by Miloševic. The uprising that followed in Kosovo was brutally suppressed by the Serbs, depriving the Albanian population of all rights.

After this, Miloševic broke down and tried to expand Serbian influence in all republics. However, this attitude would only hasten the total disintegration of Yugoslavia. In Slovenia, meanwhile, the communist party led by Milan Kucan had become increasingly liberal and intellectuals had been advocating for some time for full democracy, market economy and independence.

Slovenia independent

In December 1989, free elections were held for the first time in Slovenian history and were won by the Democratic Union of Slovenia (DEMOS), a coalition of six bourgeois parties. During the 14th Extraordinary Party Congress in January 1990, the overarching Yugoslav Communist Party broke down. The Slovenian communist party made all kinds of far-reaching demands (including a multi-party system, freedom of the press) that were obviously not honored. In February 1990, the Slovenian communists split from the Yugoslav League of Communists and continued as the "Party of Democratic Renewal".

Milan Kucan, SloveniaPhoto: MORS CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Milan Kucan, SloveniaPhoto: MORS CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

On April 22, 1990, the leader of the Slovenian Communist Party, Milan Kucan, was elected president. He declared the republic sovereign in July 1990. On December 23, 1990, a referendum was held in which more than 88% of the population voted in favor of independence. Six months later, on June 25, 1991, the declaration of independence was declared. Federal Yugoslav troops and tanks advanced in an effort to stop the process. There was even some fighting and Ljubljana was bombed on July 2, 1991. However, the Yugoslav forces were so unmotivated that they withdrew, liberating Slovenia with no more than a few dozen dead. On December 23 of the same year, Slovenia was recognized by Germany as an independent state and the new Slovenian constitution was passed by parliament. On January 15, 1992, the other countries of the European Union followed suit. In the same year Slovenia became a member of the United Nations and in 1993 of the Council of Europe.

In February 1992, the DEMOS fell apart and some of the coalition parties withdrew its support for the government of Christian Democratic Prime Minister Lozje Peterle. After parliament passed a vote of no confidence, Peterle stepped down in April 1992 and was succeeded by the liberal Janez Drnovsek who formed a center-left government. In that period there were conflicts with neighboring Croatia about, among other things, the course of the border and the limited reception of Yugoslavian refugees by Slovenia. In December 1992, President Kucan was re-elected as president for a second term. The main goal of the new government was for most of the economy to be privatized by mid-1994.

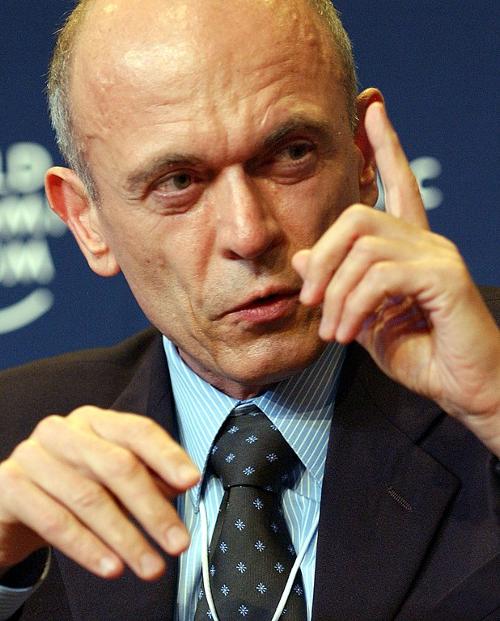

Janez Drnovšek, SloveniaPhoto: World Economic Forum CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Janez Drnovšek, SloveniaPhoto: World Economic Forum CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

The government's top priority in 1993 was to implement the so-called Property Transformation Act. Its aim was to privatize most of the economy by mid-1994. In early 1994, a power struggle broke out between Defense Minister Janša and President Kucan, which led to Janša's resignation. As a result, his party, the Social Democratic Party of Slovenia, withdrew from the coalition government. To avoid a government crisis, Prime Minister Drnovšek, also leader of the largest coalition party, the Liberal Democratic Party, merged with three smaller parties, resulting in Slovenia's Liberal Democracy (LSD) in March 1994. However, the new party was dependent on cooperation with the Christian Democratic Party.

Relations with Italy deteriorated as a result of the Osim Treaty, concluded in 1975, which established the borders of what was then Yugoslavia and Italy. However, almost twenty years later, Italy demanded compensation for the confiscation of Italian property after World War II. In 1995, Italy vetoed Slovenia's rapprochement with the EU. At the end of November Slovenia announced that it would establish diplomatic relations with the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, with which no formal contacts had been maintained since the disintegration of Yugoslavia.

In January 1996, the coalition government broke down when four Social Democratic ministers resigned, prompting President Kucan to announce early elections. The center-left Liberal Democrats (LDS) became the largest party in those November elections. Its leader, Prime Minister Drnovšek, was ordered to re-establish a government.

In February 1997 he formed a government of LDS, SLS and DPG. At the end of December 1997, President Milan Kucan was re-elected with 55% of the vote.

The foreign policy of the Drnovšek government focused on joining NATO and the European Union. On June 10, 1996 Slovenia signed a Europe Agreement with the EU and applied for EU membership. At the European Council in Luxembourg in December 1997, Slovenia was invited to the accession negotiations that started in March 1998.

However, Slovenia was not among the first group of countries from the former communist world to be admitted to NATO, which was Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic in March 1999. In 1999 Slovenia was the only one of the former Yugoslav republics to openly support NATO airstrikes in the Kosovo war. The government opened Slovenian airspace to the flights of NATO planes.

21st century

On April 8, 2000, the Drnovšek government fell after a vote of no confidence. An interim cabinet led by Andrej Bajuk bridged the period to the parliamentary elections of October 15, 2000. Ex-Prime Minister Janez Drnovšek's liberal party won (34 seats). Bajuk's party, New Slovenia, founded in August 2000, only won 8 seats. Drnovšek was re-elected as Prime Minister on November 16. At the end of November, he was able to present his fourth government, a social democratic coalition composed of LDS, USLD, SLS and SKD Slovenian People's Party and the pensioners' party DeSus. The coalition won a large majority in the Assembly: 58 seats out of 90.

In early December 2002, Prime Minister Drnovšek became the new president of Slovenia. The leader of the left government defeated right-wing Attorney General Brezigar in the presidential election. Drnovšek obtained 56% of the vote and followed a strongly pro-Western course.

Janez Janša, SloveniaPhoto: European people's party CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Janez Janša, SloveniaPhoto: European people's party CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Slovenia joined the European Union on May 1, 2004. Parliamentary elections were held in Slovenia in October 2004. For the first time since independence, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDS, center-left) of former Prime Minister Anton Rop did not become the largest party, but had to give up this place with a difference of 6 seats to the Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) of Janez Janša, who almost twice as many seats as in 2000, namely 29.

Zmago Jelincic's nationalist-tinted Slovenian National Party (SNS), which saw its seat number increase by 50% from 4 to 6 seats, was the second winner. Janša's SDS, along with the New Slovenia Christian People's Party (NSi) and the Slovenian People's Party (SLS) (member of the previous government until April 2004), had 45 seats, one seat short for a center-right majority cabinet. In order to achieve a "comfortable majority", a coalition has been formed between these parties and the Democratic Party of Pensioners of Slovenia (DeSUS), until then a member of the previous government. The Janša cabinet can therefore count on 49 of the 90 seats in the National Assembly. The opposition consists of the LDS (23 seats) of former Prime Minister Rop, the United List of Social Democrats (ZLSD, 10 seats) of former parliament speaker Pahor and the SNS (6 seats). On December 3, 2004, the National Assembly approved the coalition.

The Janša government is broadly continuing the EU and NATO policy, on which there was also broad consensus in the National Assembly during the previous governments. Prime Minister Janša has also confirmed the priority for the introduction of the Euro in 2007.

On January 1, 2007, the euro was introduced without any problems. One euro is worth 239.64 tolar, the currency introduced after the country seceded from Yugoslavia in 1991. In November 2007, Danilo Türk, an independent candidate but supported by the Social Democrats, is elected president.

Borut Pahor, SloveniaPhoto: Tamino Petelinšek/STA CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Borut Pahor, SloveniaPhoto: Tamino Petelinšek/STA CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In the parliamentary elections in September 2008, the Social Democrats narrowly won and in November 2008 Borut Pahor became prime minister of a center left coalition cabinet. Croatia officially becomes a member of NATO in April 2009, following resistance from Slovenia. In June 2009, the EU suspended negotiations with Croatia due to the lack of progress in the row with Slovenia over the exact location of the (sea) border. In November 2009, the parliaments of Slovenia and Croatia reach an agreement to allow international arbitration. Slovenia lifts the blockade it had raised against Croatia's accession to the EU. In June 2010, all this will be confirmed by a referendum in Slovenia. In September 2011, Pahor's coalition was voted out. In December 2011, the new Positive Slovenia party wins many seats, but its leader does not become prime minister. In February 2012, a center-right cabinet is formed under the leadership of Janez Jansa.

In the December 2012 presidential election, center-left ex-prime minister Borut Pahor wins. In March 2013, the coalition stumbled over austerity measures. Liberal opposition leader Alenka Bratusek becomes prime minister. In April and May, the EU indicates that Slovenia must take measures against its banking sector. Slovenia will introduce a package of measures at the end of May 2013. In November 2013, the coalition survived a vote on the 2014 budget and a plan to bail out the banks. Prime Minister Alenka Bratusek resigns in May 2014, paving the way for elections. Miro Cerar's new center-left Party (SMC) won the parliamentary elections in Slovenia in July 2014 and he will become the new prime minister. In December 2015, same-sex marriage will be agreed by means of a referendum. In March 2016, Slovenia said it will not allow most migrants to travel to Northern Europe via the Balkan route. The international court of arbitration agrees with Slovenia in the maritime dispute with Croatia. There will be direct access to international waters via a corridor through Croatian water. In September 2018, Marjan Sarec will become the leader of a center-left coalition. In 2020, power will change and Jansa will return with a center-right cabinet.

Robert Golob won a surprise victory over veteran right-wing populist Prime Minister Janez Jansa at the April 2022 parliamentary elections. His green Freedom Movement formed a coalition with the Social Democrats and the Left, and pledged to focus on environmental issues, as well as rising food and energy prices. Natasa Pirc Musar is Slovenia's first female president. She won 54% of the votes cast in the second round of the country's presidential polls on 13 November 2022. Her rival, right-wing politician and former foreign minister, Anze Logar, won 46% of the votes.

Sources

Buma, H. / Reishandboek Slovenië

Elmar

Derksen, G. / Slovenië, Istrië (Kroatië)

Gottmer

Wilson, N. / Slovenia

Lonely Planet

CIA - World Factbook

BBC - Country Profiles

Copyright: Team The World of Info