BRITTANY

History

History

Popular destinations FRANCE

| Alsace | Ardeche | Auvergne |

| Brittany | Burgundy | Cevennes |

| Corsica | Cote d'azur | Dordogne |

| Jura | Languedoc-roussillon | Loire valley |

| Lot | Normandy | Picardy |

| Provence |

History

Prehistory (to 3,000 BC)

Cairn of Barnenez BrittanyPhoto: Gerhard Haubold CC Alike 3.0 Unported no changes made

Cairn of Barnenez BrittanyPhoto: Gerhard Haubold CC Alike 3.0 Unported no changes made

Around 5000 BC, at the beginning of the Neolithic, traces of human presence become more numerous. The prehistoric people worked the land and tried to make a living here. They made axes and polished granite, which they traded in the Rhone Valley, Southeast France and England.

The social organization with division of labor was stable at the time, witness the impressive megalithic monuments. Some megalithic tombs or dolmens (“stone table in Breton”) were in the shape of a burial chamber, which you reached through a long corridor; they are huge blocks of stone covered with a burial mound. The oldest dolmen, from 4600 BC, is the cairn in Barnenez. The main concentration of dolmens is located in Carnac, some, such as the Giant of Locmariaquer, are as high as 20 meters. Just as spectacular are the menhirs, these are imposing, upright stones that probably had a religious function in a religion focused on the heavenly bodies.

Antiquity (3000 BC - 476 AD)

About 500 BC, the Armorica peninsula or "land of the sea" was occupied by Celts. Five tribes settled here: the Osismen (in Finistère), the Veneti (in Morbihan), the Coriosoliten (in Côtes d'Armor), the Riedones (in Ille-et-Vilaine) and the Namneten (in Loire-Atlantique). The Celts lived in small villages and fortified settlements, they were farmers who also worked iron, minted coins and traded overseas. The government was in the hands of a nobility of warriors and clergy, the druids. The forces of nature attributed them to various gods whom they worshiped with sacrifices. Itinerant bards (poets-musicians) sang about the exploits of mythical heroes.

Armorica and the Romans

In 57 BC, the Romans occupied Armorica and the rest of Gaul. A year later the Veneti revolted and took refuge on the rocky cliffs of the Atlantic coast. With difficulty, Julius Caesar managed to defeat them in a naval battle outside the Gulf of Morbihan. Armorica was added to the province of Lugdunensis, and remained under Roman rule for 400 years. The province was divided into five areas, which corresponded to the Celtic tribal areas. A road network and a few new small towns, such as Condate (now Rennes), Darioritum (now Vannes) and Condevincum (now Nantes) accelerated the process of romanization. While baths, amphitheaters and villas showed the influence of Roman civilization, the Celtic and Roman gods were worshiped together. In the countryside the Roman influence was present, and therefore their influence was limited. When the Roman Empire began to collapse in the 3rd, 4th century, the area became unstable. Frankish and Saxon pirates plundered the cities, and the population fled. The coastline was insufficiently protected by fortresses such as Alet (close to St Malo) and Le Yaudet (in Ploulec’h). At the beginning of the 5th century, Armorica was abandoned.

Middle Ages

Arrival of the British

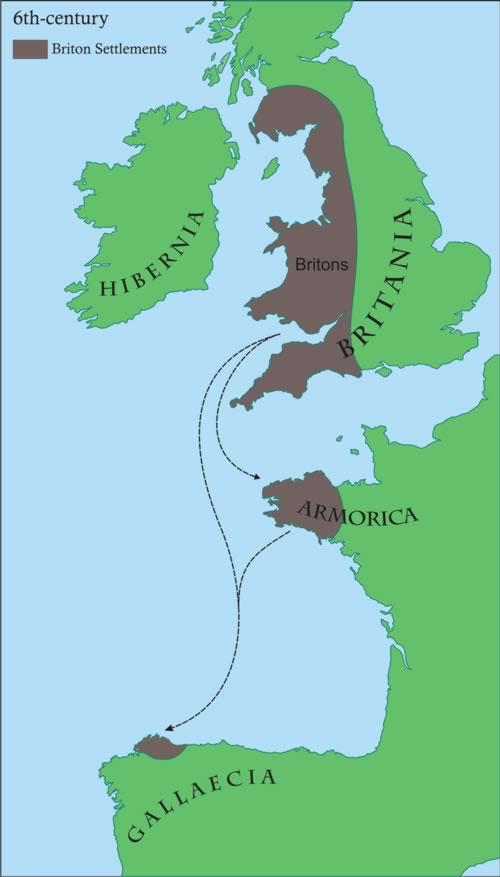

During the 6th century, large numbers of Britons (Celtic tribe) from Wales and Cornwall crossed the English Channel to settle in Armorica, which they called "Little Britain" or "Brittany". It was a peaceful invasion that lasted 200 years. Among the newcomers were many Christian monks, who introduced a Celtic variant of Christianity. Isolated hermitages or hermits were built on islands off the coast and the monasteries were led by abbots who were also itinerant bishops. They included Brieuc, Malo, Tugdual (in Tréguier) and Samson (in Dol); with Gildas, Guénolé, Méen and Jacut, who became the subject of hagiographies from the 8th century, they inspired the religious traditions that still exist today; witnesses of this are the pilgrimages and pardons such as the Troménie in Locronan.

Some 2,500 years ago Locronan was a unique center of Celtic religion. With Celtic astronomical reference points, a nemeton was constructed, a four-sided circuit of 12 km interrupted by 12 beacons corresponding to the 12 cycles of the lunar calendar. Although Benedictine monks took this Celtic place to build a priory, the perimeter of the sacred route survived the arrival of Christianity. The Celtic astronomical markers became the 12 stopping points of a procession. The word troménie is derived from the Breton words tro (round) and miniby (monastic country). The oldest troménie dates back to 1299. The grande troménie causes the pilgrim to go to heaven and is equivalent to three petites troménies.

The British immigrants introduced the typically Breton place names. The prefix plou (in eg Plougamel) or its variants plo, plu or plé, comes from the Latin plebs (the common people) and it refers to a community of Christians. Lan (as in Lannion and Lannilis) stands for "monastery". Tré (as in Trégastel), from the old British word treb, means an inhabited place. The concentration of these place names in Western Brittany, and the frequent names ending with ac in the east, from the Latin acum (as in Trignac, Sévignac), indicates a cultural dichotomy. This proves, among other things, the presence of two languages: French, derived from Latin, east of the line La Baule-Plouha, and Breton to the west of it.

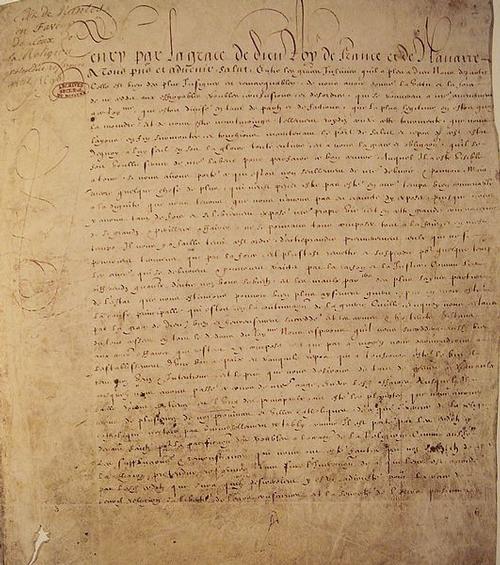

The Breton kingdom

From the 6th to the 10th centuries, the peninsula, now called Britannia, successfully defended itself against attempts by the Frankish kings who controlled Gaul to take control of the region. Many times the Merovingians invaded Brittany, but their influence was short-lived and the Bretons remained independent. Martial local leaders or viceroys provided the administration. The mighty Carolingian dynasty could only establish a buffer zone, the so-called mark, which ran from the Baie du Mont-St.-Michel to the mouth of the Loire. From about 770, that "mark" was under the control of Roland, a "cousin" of Charlemagne. In the 9th century, the Bretons established an independent kingdom, the borders of which ran to Angers in the east, Laval in the south and Cherbourg in the northwest. Noménoé, who defeated Charles the Bald at the Battle of Ballon in 845, was the first king. His son, Erispoe, succeeded him, but was murdered in 857 by his cousin Salomon. His reign, until 874, was the height of the Breton monarchy. Brittany's political independence was reinforced by the clergy, who opposed the diocese of Tours. It was the heyday of the Benedictine abbeys, they were rich centers of culture. Beautifully illuminated manuscripts and the historic Cartular de Redon (see figure) were created

The Invasion of the Normans

From the end of the 8th century, the attacks of the Scandinavian Normans increased. They sailed into Breton estuaries and inlets, plundered cities and monasteries, and sowed death and destruction. Entire monastic communities fled east and took their saints' relics with them. After the murder of Solomon in 874 chaos broke out in Brittany. Order seemed to be reversing when King Alain Barbetorte recaptured Nantes in 937 and defeated the Normans at Trans in 939. These Vikings settled in neighboring Normandy and their raids became less frequent.

Feudal Brittany

From the 10th to the 14th century, Brittany slowly became a feudal state. Some independence remained from the French and English kings, both of whom had a crush on Brittany. In the 12th century, Brittany, now a county, narrowly escaped annexation to the Anglo-Angevin kingdom of the Plantagenets. William the Conqueror, who had won the Battle of Hastings in 1066, had united Normandy and England. His successor, Henry Plantagenet, was also Count of Anjou. In 1156 he took Conan IV, Count of Brittany, under his wing. Conan's daughter, Constance, was to marry Geoffroy, son of the King of England and brother of Richard the Lionheart and John without Land. In 1203 the latter murdered Geoffroy's son, Arthur, and thus Brittany came under the rule of the English king. The French king, Philip II August, then forced Arthur's half-sister, Alix, to marry a French prince, Pierre de Dreux. Brittany then came under the direct control of the French Crown as a royal fief. The Count of Brittany paid his respects to the French king and pledged his loyalty and support. Despite these developments, a Breton state of its own developed. In 1297, the French King Philip IV the Fair made a vassal duchy of the fiefdom. Although bound to the French king as a vassal, the Count (then Duke) of Brittany was firmly in the saddle to gain independence by the 13th century. As Duke of Richmond, in Yorkshire, he was also a vassal to the Plantagenet king and thus allowed him to steer a cautious political course between the two monarchs. In Brittany, however, his authority was limited by the power of his feudal lords, who managed great fiefs from their safe, impregnable castles. They included the barons of Vitré and Fougères, on the border of Normandy, and the Viscount of Porhoët, who ruled 140 villages and 400,000 hectares of land from the Château de Josselin.

Life in the city and on the country during the Middle Ages

The inhabitants of the countryside seem to have lived more peacefully in Brittany than in the rest of France. In the west of the peninsula there was an unusual type of fiefdom that lasted until the French Revolution. Each piece of land had two owners: one owned the land and the other the buildings and the crops. Neither could be evicted without payment for the value of his property. The small towns did not have independent government. Almost all of them were fortified, and many lay on an inlet. City residents mainly lived from the linen trade. Feudal Brittany was very religious. As the population grew and new hamlets appeared, so did the number of parishes, with the prefix loc (like Locmaria) or ker (like Kermaria) in their names. The ancient pagan beliefs fused with the worship of ancient Breton saints; around their relics, pardons and pilgrimages took place. The most famous is Tro Breizj, a tour of about 650 km through Brittany, past shrines in St Malo, Dol, Vannes, Quimper, St Pol, Tréguier and St Brieuc.

Breton War of Succession

From 1341 to 1364, Brittany was ravaged by the struggles of two families claiming the duchy. This conflict became part of the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453) between France and England. The French supported Charles of Blois and his wife Jeanne de Penthièvre, the English Jan of Montfort and his wife Jeanne de Flamme. This war, in which both women were closely involved, led to such isolated incidents as the Battle of Thirty (1351). The war ended with the victory of the Montfonts: Charles of Blois was killed at the Battle of Auray (1364) and Bertrand du Guesclin was taken prisoner. The victory of Jan IV van Montfort was confirmed by the Treaty of Guérande. His family ruled almost independent Brittany for more than a century and could count on English support to thwart the French king's aspirations.

New time (1453 - 1789)

Highlight of the Breton state

In the 15th century, the Breton state reached the height of its power. The Duke of Brittany, who had the status of prince and was crowned in Rennes Cathedral, settled in Nantes. Surrounded by courtiers, it ushered in a new era in which artists were protected and Breton culture was given an important historical role. The administration (council of ministers, chancellery, court) was divided between Nantes, Vannes and Rennes. Annually, the Breton States met to vote on taxes. These intricate, heavy taxes could not finance the Duke's increasingly delirious pastimes, nor could they afford the maintenance of fortresses and an army. But by raising the necessary funds himself, the duke was able to keep the French king at bay. From the reign of John V (1399-1442), Brittany remained relatively neutral during the Hundred Years' War. Because of this the Bretons enjoyed a certain prosperity. Overseas trade developed: Breton sailors acted as intermediaries between Bordeaux and England, exporting salt from Guérande and linen from Vitré, Locronan and Léon. The population of Brittany, less affected by the plague than the rest of France, grew to 800,000 refugees from Normandy settling in the east, while many impoverished exponents of the lower nobility sought their fortune elsewhere in France. Brave mercenaries fought on both sides during the Hundred Years War. Three of them, Bertrand du Guesclin, Olivier de Clisson and Arthur de Richemon, became senior military in France. The nobles enlarged their castles and turned them into impressive residences. However, moral decay took place, the low point being the pernicious abuse of children and the brutal murder of them, during a Satanist ritual, by Gilles de Rais (figure), a brother in arms of Joan of Arc, at the Château de Tiffauges, near Nantes. In the 15th century a typical Breton variant of the Gothic architectural style developed, in which the refinement of the late Gothic was combined with the austerity of granite. A university was founded in Nantes in 1460.

End of Independence

Francis II (1458-1488), the incompetent and degenerate Duke of Brittany, was powerless against the rising royal power in France, where Louis XI deposed the last great vassals in 1477. Brittany was the only major fief remaining to be subdued. Forced to war, Francis II was defeated in 1488. In the Treaty of Le Verger, he had to surrender to the king if his successor was to rule Brittany. He died shortly afterwards. His daughter and successor, Anna of Brittany, was less than 12 years old. Anna of Brittany married Charles VIII. Louis XII, who succeeded Charles VIII, married Anna according to an agreement from the time of her marriage to Charles.

Brittany part of France

Brittany's inclusion in the French kingdom meant no fundamental difference to the Bretons. The 1532 Liaison Treaty guaranteed that their "rights, freedoms and privileges" would be respected. The province was ruled on behalf of the king by a governor, usually with connections to prominent Breton families. The interests of the population were in principle defended by the Breton States, a body which, however, was not representative, because the rural population did not have a representative. The nobility and high clergy played an important role. In the 16th century, Brittany did not suffer much from the wars of religion between Catholics and Protestants. After 10 years of struggle, from 1589 to 1598, Mercoeur had to withdraw and Henry IV signed the Edict of Nantes, ending the Wars of Religion.

Resist the monarchy

In the 17th century, royal power became absolute and the French monarchy developed into a centralized government. Local autonomy was limited and taxes rose. This revived Breton nationalism, especially among the lower nobility. This remained so until the end of the Ancien Régime. More problematic for the royal authority was the opposition of the Breton States and the Breton parliament against the intendant and the governor. While the States said they were defending Breton autonomy, they in fact supported the interests of the nobility. Tensions ran high from 1759 to 1770, culminating in the conflict between Louis-René de Caradeuc de La Chalotais, the ambitious and popular chargé d'affaires of the Breton parliament, and the Duke of Aiguillon, the authoritarian Breton commander-in-chief. The "Breton Question" heated up the mood and only died down after the death of Louis XV in 1774.

Brittany's prosperous ports

During the Ancien Régime, Brittany was economically prosperous. The ports were heavily used, both because of Brittany's inclusion in France and the new sea routes across the Atlantic. Brittany took part in the voyages of discovery with an expedition to Canada by Jacques Cartier from Saint-Malo (1534-1542). The three busiest ports were Saint Malo, Nantes and Lorient, built in 1666 as a base for the French East India Company. Economic coastal activities were disrupted by a conflict between France and England when the English attacked Saint-Malo, Belle-Île and Saint-Cast. Because of the conflicts, Colbert had an armory built in Brest around 1680 and Vauban reinforced the coastal defenses.

Modern time (from 1789 -…)

The Chouans and the Revolution

During the French Revolution, Brittany was divided into "les bleus", which supported the innovations, and "les blancs", which supported the Ancien Régime. "Les bleus" were formed by the liberal boureoisie and residents of the western Breton cantons who opposed the nobility and the clergy. "Les blancs", nobles and recalcitrant clergy, were in the majority in South and East Brittany. In 1792 the conspiracy against the Revolution by a few aristocrats led by La Rouerie failed, but ordered the recruitment of 300,000 men for the war, the Loire-Atlantique, the Morbihan and Ille-et-Vilaine revolted. The Chouans, led by Cadoudal, Guillemot, Boishardy and Jean Chouan, waged a guerrilla war. The Republicans responded with terror: 10,000 people were beheaded or drowned in Nantes. "Les blancs" are defeated. The army of Catholics and Royalists was defeated at Savenay in 1793; attempts by other nobles to go to Brittany with British help were thwarted. In June 1795, Hoche's republican army captured 6,000 of them in Quiberon and killed 750 people. Stability returned only with the arrival of Napoleon Bonaparte, who reconciled Church and State, appointed prefects and guaranteed military control through the construction of roads and garrison towns, such as Napoléonville in Pontivy. Napoleon's wars, during which the British ruled the seas, impoverished Brittany, despite privateers such as Robert Surcouf from St Malo.

The 19th century

During the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, the economy in Brittany stagnated, despite a thriving canning industry. Fishing off Iceland and Newfoundland was also an important livelihood. As poets, ethnologists and folklorists began to record Breton traditions and ancient legends, awareness of Brittany's Celtic heritage grew. The Breton language, the use of which was strongly discouraged in public education during the Third Republic (1870-1940), found ardent adherents among the clergy.

Brittany in the modern era

Telecom BrittanyPhoto: Telecom Bretagne in the public domain

Telecom BrittanyPhoto: Telecom Bretagne in the public domain

After the Second World War, Brittany recovered well. Since 1950, the Comité d'Etude et de Liaison des Intérêts Bretons has been responsible for investments and decentralized settlements, such as Citroën in Rennes and telecommunications in Lannion and Brest. Toll-free highways, high-speed trains and the construction of airports have ended Breton isolation. Thanks to the Canal connections and a strong hotel industry, this is now the second most popular tourist destination in France.

See also the history of France on TheWorldOfInfo.

Sources

Beaart, P. / Bretagne

ANWB

Bretagne

Lannoo

Bretagne

Van Reemst

Bretagne noord

ANWB

Graaf, G. de / Normandië, Bretagne

ANWB

Radius, J. / Normandië, Bretagne

Gottmer/Becht

Roger, F. / Natuurreisgids Bretagne : ontdek de onverwachte en bijzondere natuur van Bretagne

Kosmos-Z&K

Simon, K. / Bretagne

ANWB

Ward, G. / Bretagne en Normandië

Van Reemst

Wikipedia

CIA - World Factbook

BBC - Country Profiles

Last updated February 2026Copyright: Team The World of Info