HUNGARY

History

History

Cities in HUNGARY

| Budapest |

History

Prehistory and Antiquity

Bronze bracelet from the La Tène period, HungaryPhoto: Public domain

Bronze bracelet from the La Tène period, HungaryPhoto: Public domain

The current republic of Hungary is part of a large lowland, the Carpathian Basin or Hungarian or Pannonian Plain. The settlement history of the Hungarian people begins on this Hungarian lowland. The first traces of human presence in this area date back to 400,000 à 500,000 years ago, and were found along the swampy banks of the Danube and Tisza.

Around 100,000 BC. The Neanderthals hunted here, but they left for the north when climatic conditions caused their prey to disappear from these areas. This was followed by many tribes, mainly from the Balkans, most of which moved on. Different tribes, however, settled in these regions and moreover mixed together, after which the Copper, Bronze, and Iron Ages took place noiselessly.

Only when the Celts of the la Tène culture settled west of the Danube, there was somewhat of a tribal connection. They also kept in touch with the Romans, who around 10 BC. began to conquer the plains. The conquered territory was incorporated into two provinces: Pannonia Superior or Upper Pannonia and Pannonia Inferior or Lower Pannonia. The capitals were Savaria (now: Szombathely) and Aquincum (now:Óbuda, part of the current capital Budapest).

The Romans conquered this area to counter the ongoing incursions from European Russia and to protect important trade routes. In the 4th century, Pannonia was overrun by Gothic and other tribes, fleeing from the Huns led by Attila, who came from Asia and marched to Europe. The Romans could not withstand this either and left Pannonia. In 453 Attila died and the Huns withdrew from the lowlands.

They were succeeded by Ostrogoths, Gepids, Lombards and Avars, who were still in contact with the Byzantines, the heirs of the Roman Empire. Some expelled Slavic tribes settled around Lake Balaton, which they received as a fief from the ruler of the East Frankish Empire.

Middle Ages

The Arrival of the Magyars in HungaryPhoto: Public domain

The Arrival of the Magyars in HungaryPhoto: Public domain

In the 8th century, the Hungarians, a group of horsemen, moved from the east to present-day Hungarian territory and called it Etelköz. In 895 they entered Transylvania and a year later, led by Árpád they entered the lowlands where they would continue to live from now on. Árpád was the leader of the Magyars, a tribe that militarily dominated this area. In the 10th century, the Hungarians spread across the lowlands and the Transylvanian Highlands and many settled there as farmers. Other groups rented themselves out to neighboring armies or marched into the German Reich robbing and plundering. The Christianization of the Hungarians had already started and they wanted to found their own diocese.

However, the German emperor Otto I was against this because he preferred to retain power over the Hungarians himself. Prince Géza wanted to establish an ecclesiastical hierarchy at the end of the 10th century and also unite the Hungarians under one monarch. Géza was succeeded in 997 by his son Vajk, who was named István at his baptism. He married the Bavarian princess Gisela, making the state of Hungary recognized by both the Pope and the Emperor. István continued the missionary work, which earned him the famous Stephen crown and also put Hungary on the European map as an independent Christian kingdom.

István's first act was to declare all land his property, which was then lent to chieftains and to the church. However, it was the Hungarian royal family that benefited most from this and that caused bad blood. After the king's death in 1038, the chieftains sought support from the German emperor. The opposition in turn sought support from Byzantium and a counter-king, Aba Sámuel, was appointed.

Hungary became involved in a power struggle between Germany and Byzantium. Only under the rule of Béla I, who ruled from 1060 to 1063, did the Hungarian royal family recover some of its power.

Under LászlóI and Kálmán I pursued a policy of expansion in Hungary and, for example, part of Croatia was conquered, creating a free passage to the Mediterranean. Bosnia and Dalmatia were conquered at the expense of Byzantium. As a result, Hungary gradually became a superpower that could no longer be ignored in Europe.

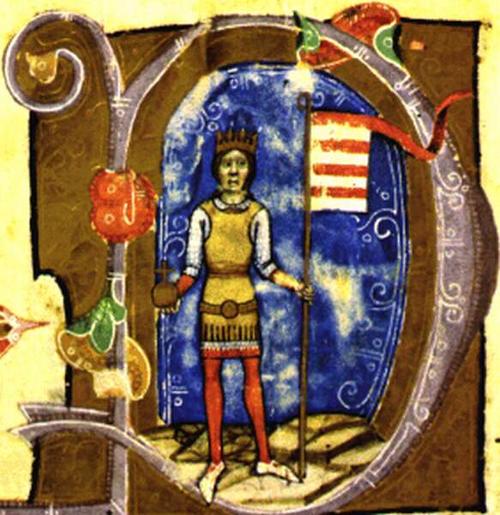

Béla III of HungaryPhoto: Public domain

Béla III of HungaryPhoto: Public domain

Under Béla III, Hungary strengthened its position and opened the borders to Western influences that the feud had.all character. The Hungarian court and the nobility settled in beautiful castles and the barter trade was replaced by a guided money economy. Under András II, more and more landed gentry took over the administration of the estates and in 1222 he even agreed to a 'Golden Bul', stating that one had the right to carry out armed resistance against the monarch. Under Andres' son, Béla IV, enemy tribes from the east threatened to invade Hungary.

Béla strengthened the borders but in 1241 the Mongols invaded Hungary without much trouble. Hungary was looted for a year and then the Mongols left, never to return. Other European powers did not intervene for Hungary, but thought they could profit from a weakened Hungary. When all was over, Béla had a number of fortresses built, including Buda on the right bank of the Danube.

In 1301, the rule of the Arpads came to an end; there was no male line succession and the Arpad dynasty died out silently. The Hungarian nobility then chose a Bohemian king, then a Bavarian king, and finally the pope-backed king of Naples, Charles Robert III, ascended the throne. In the rest of the 14th century, the balance of power in Hungary became more stable and the focus was more on international politics, more or less forced by the expansion policy of the Turks. The attempts to remove rural areas such as Dalmatia , Slavonia , Moldova, Croatia and to strengthen Wallachia met fierce opposition from local rulers.

Meanwhile, Lajos the Great had come to power and was succeeded in the late 14th century by son-in-law Sigismund (Zsigmond) of Luxembourg, who later became King of Bohemia and Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Zsigmond jealously tried to protect and even expand Hungarian interests. However, a campaign against the Turks in 1396 was lost at Nikopolis, despite help from the Burgundians. In 1417 the Turks broke through the Hungarian borders and inland a massive peasant uprising took place, but was crushed.

Fifteenth and sixteenth century

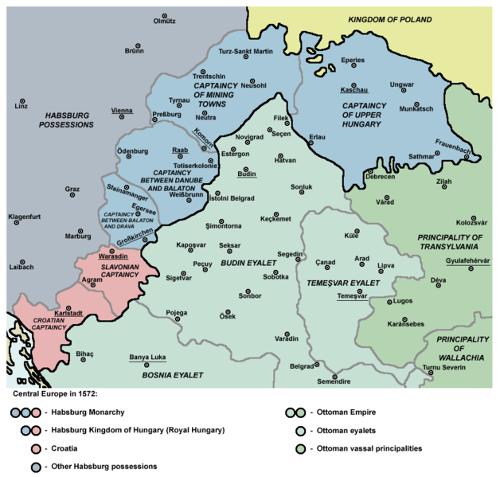

Hungary, Map of Central Europe 1572Photo: PANONIAN in the public domain

Hungary, Map of Central Europe 1572Photo: PANONIAN in the public domain

In the mid-15th century, a famous Hungarian family of landowners, the Hunyads, emerged. The first great landowner was János Hunyadi, who also became regent over the young László, son of Albert of Habsburg. Albert was the first king of a new dynasty to rule Hungary. In 1456 János died of the plague and a power struggle ensued between the high nobility and the cities and the low nobility. The high nobility subsequently appointed Mátyás Hunyadi as king, bringing the Hunyadi family to the height of its power.

In an alliance with Emperor Friedrich III, Mátyás Moravi, Siliezi and adding Lower Austria to the Hungarian Empire and making peace with the Turks. The Mályátas period brought domestic peace and considerable economic progress, and he was known as the 'righteous king'. After Mátyás death, the church and nobility chose the Bohemian prince Wladislaw as his successor, who would later become king. It was also decided to dismantle the royal army and hire mercenaries in its place. This made it easier to keep all power in their own hands.

In 1514, the Golden Bull was replaced by the “tripartitum”, which established the rights of the nobility. That same year, Franciscan monks formed a peasant army to go on a crusade. The nobility saw this as a serious threat and banned the army. This army then turned against the nobility, but this revolt was brutally suppressed. By the landlords of Transylvania and Temesvár. In 1521 this development was thwarted by the Turks, who after the conquest of Belgrade pushed through to the Hungarian lowlands. Then it turned out that the newly disbanded army would have come in handy. A hastily assembled army was devastated by the Turkish armies of Süleyman in the Battle of Mohács on 15 August 1526. This situation would have divided Hungary until the end of the 17th century. country. In fact, a domestic power struggle ensued between János Zápolya, who had been elected by the Diet, and the Habsburg Archduke Ferdinánd, who was enthroned by the nobility. The intention of both parties was to obtain foreign military support because János was the son-in-law of the king of Poland and Ferdinánd was the brother of Charles V. Zapolya dolf lost but entered into an alliance with the Turks, causing the sultan of Transylvania granted some autonomy.

In 1541, Buda was conquered by the Turks, and Hungary was in fact made up of three distinct parts. The Turks ruled in the triangle Pécs-Esztergom-Szeged. To the west of this was the small independent Habsburg kingdom of Hungary with its capital Pozsony (now: Bratislava in Slovakia), to the east, Transylvania under the Turkish vassal János Zsigmond. The Turks tried to advance to Vienna, but failed to get past a number of Hungarian settlements.

In 1568 a status quo was reached by a treaty between the sultan and Maximilian, the emperor of Austria. Transylvania flourished and the most diverse population groups lived peacefully side by side. The city of Debrecen became a stronghold of Protestantism. The Turks hardly oppose this because it would reduce the influence of the Catholic Habsburgs.

Seventeenth century

Leopold I, HungaryPhoto: Public domain

Leopold I, HungaryPhoto: Public domain

The serf farmers were actually the only population group that had much less than the rest of the population. Army commander István Bocskay was therefore able to deploy a mercenary army, mainly consisting of peasants, in the fight against the aggressive Habsburg troops.

In the period 1604-1606, the Habsburgs were expelled from the Great Plain of Hungary and the peasants took their place. Bocskay also conquered the Habsburg part of Hungary, which was merged with the Great Plain under his successor Gábor Bethlen. The Habsburgs recovered but were whistled back by the Treaty of Münster in 1648, thus securing the independence of Transylvania was confirmed.

The genus Rákóczi now came to play an important role. An attempt by György Rákóczi to conquer Poland failed, giving Emperor Leopold I (Lipót) the chance to go to war against the Turks and winning a victory at Szentgotthárd in 1664. By paying a lump sum payment tried to prevent the Turks from continuing to devastate the country (Treaty of Vásvár). Punitive expeditions against Rákóczi continued, however, and Transylvania suffered a lot from that. It became clear that Austria cared little about the Hungarian desire to regain independence.

Rebellious nobility was beheaded or imprisoned and the army came under the command of Leopold I. However, dismissed soldiers regrouped again and under the leadership of Imre Thököly from Slovakia and supported by the Rákóczi’s, the pro-Habsburgs were expelled from large parts of Hungary in the period 1678-1682. The road to Vienna seemed to be open to the Turks now, but the “March to Vienna” of the Turks in 1683 ended in a painful defeat for the Turkish sultan.

Leopold then decided to raise a coalition army (Austria, the Habsburg buffer state, Poland and Venice, or the Holy League). In 1686 Buda was recaptured and in 1688 the liberation of Belgrade followed. After negotiations in Karlovice in 1699, practically all of Hungary had been recaptured from the enemy.

Eighteenth century

Empress Maria Theresia, HungaryPhoto: Public domain

Empress Maria Theresia, HungaryPhoto: Public domain

Although Hungary had recaptured its territory, political freedom was still far from a fact. Because of the personal union with Austria, the Habsburgs remained in fact rulers and the country was divided among officers and members of the Teutonic Knights. The Hungarian plain was then occupied by Swabian and Serbian immigrants and the cities 'Germanised' all the way. It was clear that the aim was the total abolition of the Hungarian state and the population was forced into assimilation.

It is clear that this situation would inevitably lead to an uprising. Under Prince Ferenc Rákóczi II began in 1703 from Transylvania the war of freedom. However, this was not a success and in 1711 a peace treaty was signed with the Austrian emperor. Yet this failed uprising paid off: the empire recognized the sovereignty and constitution of the kingdom of Hungary. At that time, the repopulation of the Hungarian territory (Hungary, Slovakia, Slavoni and Croatia) continued as usual and Croats, Germans, Serbs, Slovaks and Romanians settled. This meant that after 1700 the native Hungarians made up only about 40% of the population. Transylvania had meanwhile become predominantly Romanian, was also given more autonomy and was separated from the rest of Hungary by a military zone.

After the Hungarian parliament approved female succession, Empress-Queen Maria Theresa came to power in 1740. It was quite popular with the Hungarians due to a fairly mild rule and quite silently Hungary was incorporated into the Austro-Hungarian double monarchy in 1768 and from that time on it was ruled by decree.

Maria Theresia was succeeded by József II, who was more of a despot although he did restore religious freedoms, put an end to serfdom and curtailed the power of the nobility and the church. Under the very conservative Ferenc I, resistance against the Habsburgs increased again and certain groups, notably progressive citizens and nobles, wanted an independent Hungary again. An uprising in 1795 was bloody suppressed, but a call from Napoleon to revolt against Habsburg rule was ignored. Economic reforms were set in motion under the influence of the industrial revolution that was set in motion at that time.

Nineteenth century

Lajos Kossuth, HungaryPhoto: Public domain

Lajos Kossuth, HungaryPhoto: Public domain

In 1848 almost all of Europe was dominated by revolutions. and cities like Vienna and Pest could not escape it either. Revolutionaries came up with a whole package of demands that boiled down to the abolition of the feudal form of government. This was successful inasmuch as Count Batthyány became prime minister of an autonomous government and new laws passed by parliament would be signed by King Ferdinánd. The uprising ended in a total chaos of each other distrustful population groups and the promises from Vienna were not at all trusted. (now: Cluj in Romania). The revolutionary government fled to Debrecen to organize a counterattack from there, the initial aim of which was to destroy Transylvania to recapture. This worked, and on April 14, 1849, Lajos Kossuth proclaimed the independent republic of Hungary with Szemere as head of the new government. Kossuth became president but had no executive power. Austria, led by Emperor Franz Josef, responded immediately, calling on Russia for help. That was a good move because on August 13 the independent republic of Hungary came to an end and President Kossuth fled into exile.

The Austrians now imposed a reign of terror and increased taxes and the official language became compulsory German. In 1859, however, the Austrians were defeated by Italy and France and the Emperor passed over to Hungary to a stabilization policy, influenced by Empress Elisabeth or “Sissi”. Several compromises were made and in 1867 Franz Josef announced the “Ausgleich” off. This meant that Hungary became an autonomous kingdom again, and would henceforth be treated completely equal to Austria. The newly independent parliament took up residence in Buda and the government was led by Gyula Andrassy.

Former President Kossuth was almost alone in his criticism of the dual state of Austria-Hungary, the people were generally very enthusiastic. Only the lower layers of the population did not get better in these times of industrialization and agricultural reforms. At the top, struggles between Habsburg supporters and Kossuth remained volutionaries persist.

From this time on, the socialist movement throughout Europe grew stronger and nationalist sentiments grew stronger, including in Hungary. A precursor to full independence was the reintroduction of Hungarian as the official language.

Twentieth century

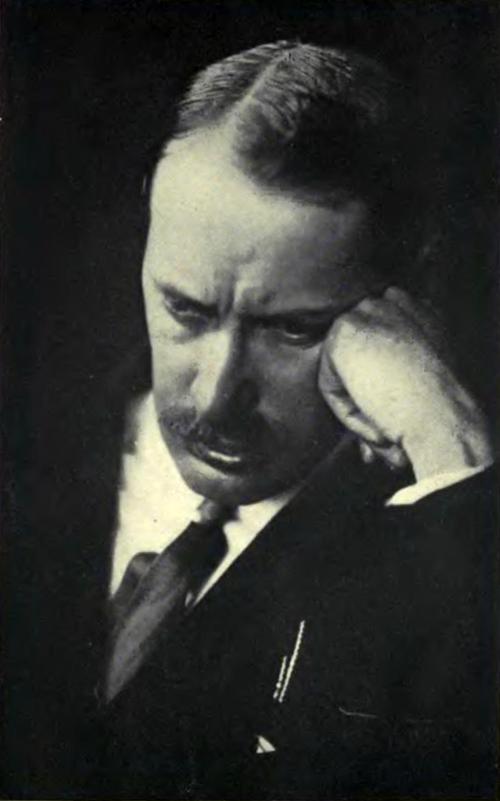

Károlyi, HungryPhoto: Veres in the public domain

Károlyi, HungryPhoto: Veres in the public domain

The assassination of Franz Josef's successor, Franz Ferdinand, was the immediate reason for the First World War and Hungary could of course not escape this as a partner of Austria. The course of the war offered Hungary an opportunity to continue on the path of independence and, under the leadership of Count Mihály Károlyi, demanded secession, reforms, concessions to ethnic minorities and peace, but the latter would still be a a few years.

After the war, it was chaos in Hungary, but it was Károlyi who set up a National Council. After the war, agreements were also made about the new borders of Hungary, but these agreements were so vague that the dual monarchy fell apart and areas were annexed by ethnic minorities. On November 16, 1918, parliament proclaimed the republic and Károlyi was appointed president. The provisional government of Károlyi was soon overthrown and the communists tightened their grip on domestic politics and on March 22, 1919, proclaimed a 'council republic' resembling the form of government of the Soviet Union.

The Foreign Affairs Commissioner Béla Kun took full control of power and proved himself a true communist by dividing the land among peasant cooperatives, and banks and nationalize companies. The right-wing opposition revolted and the Czechs and Romanians offered military aid. The Romanians even invaded Budapest and the communists were devastated. After this, more or less free elections were held in January 1920, which resulted in a victory for the Christian nationalists and small farmers.

On June 4, 1920, the major European powers decided what would happen to Austria and Hungary (Treaty of Trianon). It became a painful event for both because they were forced to give up large areas. Austria lost South Tyrol, Bohemia, Galicia, Slovenia and Bosnia; Hungary lost, among others, Slovakia, Transylvania and Croatia. For the border strip between the two countries, a popular vote was held in which the inhabitants of that area were allowed to choose what they wanted to belong to.

The territory of Hungary decreased from 325,411 km2 to 92,963 km2 and the population decreased from 21 to 7, 5 million. More than 3 million Hungarians came under foreign rule. Although the monarchy was formally restored, fleet warden Horthy appointed himself regent and King Károly IV was exiled to Madeira.

Internationally, efforts were made through the great powers to regain Hungary's old borders. In particular Germany, Austria and Italy were not against this, and it was no wonder that the rising National Socialism in those countries also caught on in Hungary. A number of conservative officers took over from the so-called ‘arrow crosses’ (nyilasok), a Nazi, anti-Semitic organization. Although this party was banned several times, it was always able to recover thanks to pressure from Germany.

World War II

Horthy and Hitler, HungaryPhoto: Public domain

Horthy and Hitler, HungaryPhoto: Public domain

In 1938 the Hungarian position was rewarded by the Axis powers with the allocation of strip of land in Slovakia where a Hungarian minority was strongly represented. Hungary itself annexed Karpatho-Ukraine or Ruthenia and wanted to recapture even more ex-Hungarian areas. As a result, Hungary increasingly surrendered itself to the Germans and, among other things, a declaration of war on the Soviet Union followed. Hungary did manage to stay largely outside the real war acts. In the end, Hitler did not fully trust the Hungarians and on March 19, 1944, Hungary was occupied by the Germans and important politicians were arrested.

Jews met the same terrible fate as in other occupied countries. Horthy then indicated that he wanted to defect to the Allies and was immediately replaced by the pro-German Ferenc Szálasi. The eventual result was that the entire country was looted by both Russian and German soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Hungarian civilians in Russian forced labor camps disappeared.

In October, the Hungarian military units surrendered to the all-powerful Russian divisions and a provisional government of communist exiles was installed. In November 1945 the first post-war elections were held, which were unexpectedly won by the small farmers' party. In itself, this victory was not much because the communists continued to occupy the most important government posts and slowly but surely the communists (read: Soviet Union) took control on all fronts.

On February 1, 1946, the monarchy became formal. replaced by a republic and Hungary was forced to accede to the Warsaw Pact (counterpart to NATO) and COMECON (counterpart to the EEC). Furthermore, Hungary had to forgo foreign aid, banks and large companies were nationalized and the Soviet Union refused to withdraw its troops from the country.

The politically active Cardinal Mindszenty and declared opponent of the communists was sentenced to life imprisonment. From 1948 on, Hungary was proclaimed a people's republic and ruled by only one party: the communist MDP led by Mátyás Rákosi. Hungary soon became a Soviet clone with expropriation of private property, collectivization of agriculture and emphasis on heavy industry. Furthermore, the party and the (security) police carried out a reign of terror that claimed many victims.

Hungarian uprising

Hungarian uprisingPhoto: Házy Zsolt CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Hungarian uprisingPhoto: Házy Zsolt CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

After the death of the Soviet leader Stalin in 1953, Rákosi was succeeded by Imre Nagy, who was already deposed after a year and a half due to his too liberal attitude. After a short period of Rákosi, he was replaced in 1956 by Erno Gero. On October 23, 1956, a fairly innocent demonstration by students and workers escalated. The demonstration was violently broken up and on October 25 a veritable popular uprising broke out across the country.

Symbols of Stalinism were destroyed, Cardinal Mindszenty was liberated and Imre Nagy was proclaimed leader of the uprising. Large parts of the army, led by General Pál Maléter, also sided with the insurgents. They demanded, among other things, free elections and the withdrawal of Russian troops from Hungarian territory. General Paléter and some other rebel leaders were then invited to come to Moscow to discuss the situation that had arisen. However, this was a trap and the entire group was arrested. Subsequently, tanks were sent to Budapest and broke the resistance of the Hungarians in four days, at the cost of about 3,000 dead.

On November 4, 1956, a new government was formed under Russian supervision under the leadership of János Kádár. The MDP was replaced by the MSzMP, the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party. This was the signal for about 200,000 Hungarians to flee abroad and for those who stayed to declare a general strike. The government intervened very hard: tens of thousands of Hungarians were captured and figures such as Nagy and Maléter were executed.

Back to democracy

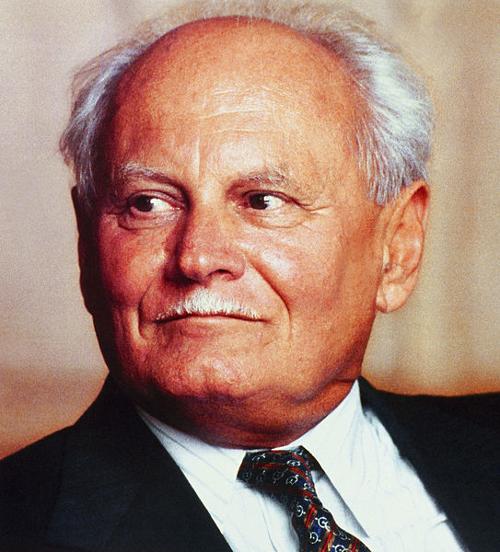

Arpád Göncz, HungaryPhoto: SZDSZ CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Arpád Göncz, HungaryPhoto: SZDSZ CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In the 1960s, the economic deteriorated situation in Hungary and a series of reforms were introduced in 1968. There was again more room for private initiative and prosperity rose slightly. Kádár, who led Hungary from 1956 to 1988, pursued a thrifty and smart policy that made Hungary a fairly stable country with one of the best-managed economies in the Eastern Bloc.

The second half of the years eighty were dominated by the radical reforms (perestroika) in the Soviet Union by Michael Gorbachev. Hungary was immediately at the forefront of its own reforms. There was more freedom of the press and the freedom to travel increased, because the border barriers with Austria were partially removed. Major steps towards democracy were taken in May 1988, only the struggle between the Imre Pozsgay reformers and the conservatives continued.

October 1989 saw Rezsö Nyers to lead a new party. He was one of the leading figures behind the cautious reforms of the 1960s and 1970s. The communist party was now formally dissolved for the second time and replaced by the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSzMP). And so the Hungarian People's Republic became a “normal” republic. Moscow continued to let go of the other Eastern Bloc countries, so that a real armed conflict did not occur this time. On the contrary, Hungary experienced a‘velvet” revolution with the first free regional elections as early as 1989.

On March 25 and April 8, 1990, a democratic parliament was elected for the first time since 1947. Thirty parties participated in the elections, of which only six entered parliament. The Hungarian Democratic Party (MDF) provided the first Prime Minister and the first appointed president became Árpád Göncz of the Alliance of Free Democrats (SzDSz). The 1994 elections were won by the former socialists and received an absolute majority in parliament. The left coalition government led by Gyulá Horn introduced a stringent austerity program aimed at achieving macroeconomic stabilization. This initially led to a reduction in economic growth and wages. From 1997, however, the economy showed signs of recovery again.

On July 8, 1997, Hungary became a member of NATO. The May 1998 elections brought an end to the MSzMP government. The right-wing liberal Fidesz party (Federation of Young Socialists) of the controversial Victor Orbán won the elections and formed a coalition with the Conservatives and the Christian Democrats.

21st century

Ferenc Mádl, HungaryPhoto: Unknown CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Ferenc Mádl, HungaryPhoto: Unknown CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

The second round of the parliamentary elections in April 2002 led to a change of power. Prime Minister Orbán's ruling conservatives were narrowly defeated by a coalition of socialists and liberals. Although Orbán's party got the most seats in the new parliament, it failed to win over the majority of voters. The Socialists (MSzP) and Liberals (SzDSz) won a narrow majority with 198 of the 386 seats.

Since August 2000, Ferenc Mádl has been President of Hungary. Hungary joined the European Union on May 1, 2004. A few months after the historic accession to the EU, Prime Minister Medgyessy tried to reshuffle his cabinet. However, Medgyessy lost the confidence of the coalition partners and subsequently offered his resignation. On the recommendation of the MSzP, President Mádl appointed former Minister of Youth and Sports Ferenc Gyurcsány Prime Minister. Gyurcsány was sworn in on September 30, 2004. The Prime Minister Gyurcsány's government program, entitled 'New dynamism for Hungary', announces the government's intentions to promote economic growth.

The Head of State is the President, currently LászlóSólyum, elected by Parliament on 7 July 2005 (took office 5 August).

Following the April 2006 parliamentary elections, the Gyurcsány-II government was officially installed on 9 June 2006. This government is headed by the (re-elected) socialist prime minister Gyurcsány (took office in 2004). The government is formed by a coalition between the (former communist) Socialist Party (MSzP) and the Left Liberals (SzDSz), which has continued since 2002. It was the first time since the fall of the Berlin Wall that there was no change of government after the election. In April 2008, the Alliance of Free Democrats left the coalition and Gyurcsány reshuffled the government. In March 2009, Gyurcsány announced its resignation to make way for a new leader who can count on broad support to address the economic challenges. Gordon Bajnai, the economic minister, becomes Hungary's new prime minister in April 2009.

Victor Orban HungaryPhoto: European Peoples's Party CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Victor Orban HungaryPhoto: European Peoples's Party CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

In April 2010, conservative opposition Fidesz party wins elections, with its leader Viktor Orban taking over as prime minister. The extreme right-wing Jobbik party comes with 47 seats in parliament. Hungary will be the new EU president for six months from 01-01-2011. There is much criticism from other European countries of the controversial media law that the country passed on December 20. The new media law appoints a government-appointed media authority to judge whether journalists are 'moral' and 'objective'. News programs are also allowed to spend up to 20 percent of their airtime on crime, so as not to frighten the people. In May 2012, Janos Adler becomes President of Hungary. In the years 2013 and 2014, there were critical comments back and forth between the EU and Hungary about the fifth amendment which should, among other things, shape civil rights. In April 2014, Fidesz won the parliamentary elections for the second time. In 2015 and 2016, Hungary has a strong inhibiting role in the admission of refugees, Prime Minister Orban of Hungary actually does not want to accept immigrants at all, the EU is threatening with sanctions for countries that do not comply with the distribution key. In October 2016, the population supported the government's immigration position in a referendum. Also in 2017, the EU is critical of Hungary, partly because of the government's attempts to close the liberal central university of Budapest. In the years that followed, Orban's policy continues to cause concern for the EU. The erosion of the rule of law and the lack of freedom of the press are the biggest stumbling blocks. In December 2020, Hungary threatens to vote against the EU budget together with Poland because recipients of EU money can be held accountable for their dealings with the rule of law.

Orban won a fourth straight term in power at elections in April 2022. The former minister for the family, and a member of parliament for the governing Fidesz party, Katalin Novak was elected president in May 2022 in a parliamentary vote.

Sources

Boedapest en Hongarije

Michelin Reisuitgaven

Fallon, S. / Hungary

Lonely Planet

Hongarije

Lannoo

Hoogendoorn, H. / Hongarije

ANWB

CIA - World Factbook

BBC - Country Profiles

Last updated June 2025Copyright: Team The World of Info