PICARDY

History

History

Popular destinations FRANCE

| Alsace | Ardeche | Auvergne |

| Brittany | Burgundy | Cevennes |

| Corsica | Cote d'azur | Dordogne |

| Jura | Languedoc-roussillon | Loire valley |

| Lot | Normandy | Picardy |

| Provence |

History

Prehistory

Archaeological excavations on the alluvial terraces and in the peat bogs of the Somme Valley have revealed the remains of extinct animals such as elephants and rhinoceroses in silt, sand and gravel deposits. An important site was the prehistoric site of Saint-Acheul, a suburb of Amiens.

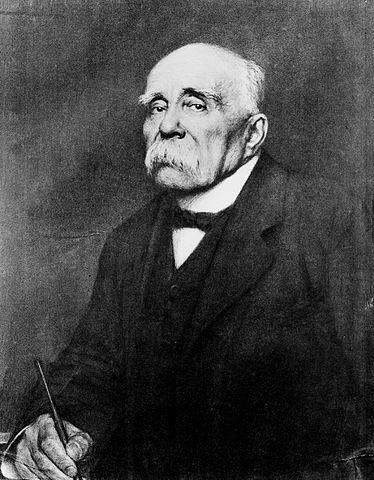

Approximately 500,000 years old man-made two-sided flint hatchets were also found there. The presence of mankind at that time is also confirmed by finds in the Oise and Aisne valleys. The main prehistoricists who investigated the Saint-Acheul site were Victor Commont (1866-1918), Jean Albert Gaudry (1827-1908) and Louis Laurent Gabriel de Mortillet (1821-1898). The period in which these hand axes and other stone tools were made was called the Acheuléen by De Mortillet. The hand axes were described by De Mortillet in 1872 and associated with the hunter-gatherers Homo ergaster and Homo heidelbergensis, who lived from Africa to the Near East and the ice-free parts of Europe. The presence of Homo heidelbergensis, ca. 450,000 to 300,000 years B.C., was confirmed by archaeological findings at Abbeville, Amiens and Cagny.

Gabriel de Mortillet, pre-historian working in PicardyPhoto: public domain

Gabriel de Mortillet, pre-historian working in PicardyPhoto: public domain

In the Middle Paleolithic, ca. 90,000 to 35,000 BC, Neanderthals settled in Picardy, and the stone culture of that time is called the Mousterian, after Le Moustier, a village in the Périgord.

Around 35,000 B.C., in the Late Paleolithic, Homo sapiens arrived in northern France and important cultures and industries at the beginning of that period were the Magdalenian and the Périgordian in the valleys of the Oise and the Somme.

In Amiens, in the Renancourt district, a limestone Venus statue was found in July 2014, dating from the Gravettian (28,000 - 22,000 BC). Near Compiègne, a camp of reindeer hunters, Cro-Magnon, was found around the same time.

The Mesolithic, ca. 9000 to 6000 B.C., is a transitional period between the Paleolithic and Neolithic. After the last ice age, from ca. 9000 to 8000 B.C., Picardy became a forest area. The archaeological culture of that time was the Tardenoisien, with striking trapezoidal arrowheads and small flint blades, among others found in Fère-en-Tardenois, Villeneuve-sur-Fère and Coincy in the Aisne department. The Tardenoisien lasted from ca. 6500 to 6000 B.C., the beginning of the Neolithic.

During that Neolithic period, around 4 000 B.C., the Danubian civilisation invaded Picardy with such things as grain cultivation, pottery and cattle breeding; corpses were buried as individuals. From then on, the man was not only a warrior, but also became a producer. Open spaces in forests during the Chasséen civilisation (4500-3500 BC) were used to build houses, a kind of vesrified villages arose, for example in Cuiry-lès-Chaudardes in the Aisne department. In Villers-Carbonnel in the Somme department, a female statue from this period was found in 2011.

Around 2500 BC, the Chasséen civilisation was more or less succeeded by the Late Neolithic Seine-Oise-Marne culture (2500-1600 BC), whose core was in the Paris Basin, but whose offshoots were in the Meuse valley, Flanders, southern Netherlands and the Vlaardingen culture in the west of the Netherlands. Remains in Picardy from this period are the megalithic cemeteries at Feugneux, Dameraucourt and Boury-en Vexin in the Oise, Cierges and Marchais in the Aisne. Menhirs can be found in Bavelincourt, doingt and Eppeville in the Somme department, Borest in Oise and Haramont, Orgeval and Pargny-les-Bois in Aisne.

Menhir near Borest, PicardyPhoto: P.poschadel CC 2.0 France no changes made

Menhir near Borest, PicardyPhoto: P.poschadel CC 2.0 France no changes made

The discovery of flint tools from Picardy in Grand-Pressigny, just south of Tours, and in Ploéven in the Finistère department in the region of Brittany, show that there was already a lot of trade at that time.

Protohistory

The Proto period or 'early history' is the transitional period from prehistory to antiquity. At that time, the civilisation in Picardy did not yet have its own writing system, but it was already being described by neighbouring peoples.

Bronze objects were introduced into Picardy by migrants around 1650 BC and trade was conducted via routes to Ireland and Cornwall. Objects such as bracelets, pins and daggers have been found frequently here, and axes especially on the coast.

From 1200-1100 BC, remains of the urn field culture have been found in Oise and Aisne, which was situated in the late Bronze Age and was characterised by urn deposits on an urn field.

The urn field culture was succeeded by the first Iron Age culture, the so-called Hallsttatt culture, which lasted from 750-700 B.C. During the Hallstatt period, salt was mined at the mouth of the Canche river, and archaeological findings show that there was contact with the Greek civilisation. Tin was also transported to the Mediterranean via the Somme and the oppidum of Vix (Cote d'Or). Around 500 BC, this trade route was abandoned and the Mediterranean was reached mainly via the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean.

History of France from ancient times

In the Bronze Age, a center of bronze industry and trade emerged in Brittany. From the Rhineland in the late Bronze Age, the Urnfield culture spread throughout France. In the Iron Age, the Hallstatt culture (750-450 BC) and the La Tène culture (450-50 BC) were important. Of great significance in this period was also the foundation of the Greek colony of Massilia (now: Marseille), which resulted in, among other things, trade contacts with the classical world. Massilia (Marseille) at the age of emperor CaesarPhoto: Cristiano64 CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Massilia (Marseille) at the age of emperor CaesarPhoto: Cristiano64 CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In Northern France, Marne culture flourished around this time. A lot of bronze crockery has been found from this period and even complete trolleys. All this points to a dichotomy in prehistoric society with a social elite but also feudal traits.

With the Gallic Wars of Caesar (58–51 BC) and his incorporation of "Gallia" into the Roman Empire, prehistory and antiquity come to an end.

Middle Ages

Christianity was first introduced to France in the 2nd century. The first Christians were still persecuted, but the turning point came in 312 with the conversion of King Constantine. Christianity then became the official state religion. By 500, the church had acquired a powerful position alongside the state and exerted great influence.

From about 300 on, the Roman Empire began to decline and it was extremely difficult to defend Gaul against barbarian tribes from Germany. After 400 the Vandals invaded en masse and Attila the Hun advanced as far as Eastern France and the Romans withdrew to Orléans. In 455, Rome itself was conquered and Gaul became prey to the West Goths, Burgundians, Alemanni and Franks.

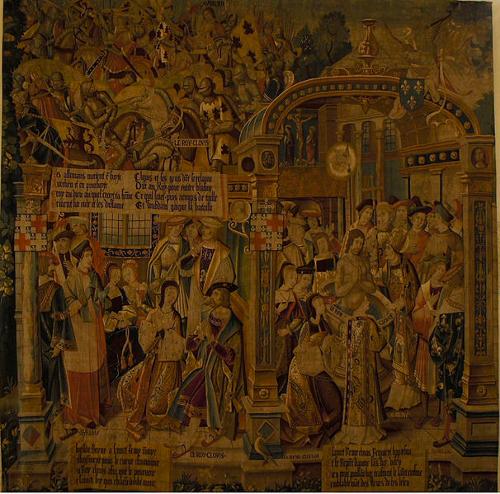

In 481 Clovis became the first Merovingian king of the Salian Franks, laying the foundation for modern France. Clovis converted to Christianity and married Clothilda, a Burgundian princess, thus increasing the power of the Franks. After the death of Clovis, a succession war ensued between marauding feudal lords who tried in vain to maintain authority and order. During this time it was not the Frankish kings, but their officials, the stewards, who exercised actual power. Baptism of Clovis I in 496, FrancePhoto: Garitan CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Baptism of Clovis I in 496, FrancePhoto: Garitan CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In 732 Charles Martel, one of these stewards, seized power and became the first Carolingian king. Martel gained much power, but Gaul only became one through his grandson Charlemagne, who was crowned emperor by the Pope on December 25, 800. He became the founder of the Holy Roman Empire and managed to keep a number of countries in Central and Western Europe together. After his death the empire was divided among his sons and the western part, Francia, fell prey to the expansion drive of neighboring dukes.

After the Treaty of Verdun, concluded in 843, the area west of the rivers Scheldt, Meuse, Saône and Rhône came under the rule of Charles the Bald. His successors showed little decisiveness and several territorial monarchs seceded from the Frankish empire. Under Charles III the Fat, the Frankish unified kingdom was somewhat restored, but in 887 Charles was deposed and the West and East Frankish empires gradually emerged from which France and Germany would eventually emerge.

Around the year 900 the threat of the predatory Normans increased but it was Charles III the Simple who managed to make an agreement with their leader Rollo that would limit the Normans to their raids to Normandy. Other leaders of the Frankish house, such as Robert I and Louis IV, had much to do with the great vassals. During that time, a number of territorial principalities arose, including Flanders and Normandy. Ultimately, the Carolingian House died out with the death of Louis V. Statue of Hugo Capet, king of France (987-996)Photo: Thesupermat CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Statue of Hugo Capet, king of France (987-996)Photo: Thesupermat CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

With German support, Hugo Capet (987-996) was elected king and the dynasty of the Capetians began, which succeeded in making the monarchy hereditary. The power of the Capetians ceased to the south of the Loire and to the north of the Loire was mainly based on the support of a few bishops. Louis VI was the first to keep the great vassals in check and in 1124 he managed to prevent an invasion by the German emperor. His son Louis VII married Eleanor of Aquitaine and thus managed to extend his influence to the Pyrenees.

After the divorce of Louis and Eleonora in 1152, Eleonora married Henry II Plantagenet, who thereby could add the South of France to his empire. In 1154, Henry also became king of England and therefore posed a great threat to France. However, Louis VII's successor, Philip II August, managed to recapture large parts of France. The battle won against the Anglo-Flemish coalition at Bouvines in 1214 gave him a lot of prestige in France and Europe.

In the thirteenth century, various monarchs were able to further expand the French crown domain, including parts of Languedoc and Toulouse. The first absolute monarch was Philip IV the Fair, who came into conflict with the Vatican in Rome, among other things. The conflict resulted in the appointment of a Pope Clement V, subject to the king, who even settled in Avignon in the south of France. Philip IV was succeeded by his three sons, Louis X, Philip V and Charles IV respectively, the last of the direct line of the Capetians. Picture of Philp IV the Fair, king of France (1285-1314)Photo: Rijksmuseum in the public domain

Picture of Philp IV the Fair, king of France (1285-1314)Photo: Rijksmuseum in the public domain

After Charles IV his son Philip VI came to power, but the English king Edward III also made claims to the French crown. This eventually led to the so-called Hundred Years' War in which France initially suffered one defeat after another. The bubonic plague epidemic of 1348-1352 claimed the lives of 4-5 million people, about 25% of the French population. In 1360, the peace of Brétigny was concluded, which forced France to cede some areas (including Aquitaine and Calais) to England, but managed to keep Burgundy. Under Charles V, France managed to recover definitively.

In 1392 Charles VI was declared insane and a council of regency in fact assumed power

Fifteenth and sixteenth century

Of course, that was not without problems and in particular John the Fearless of Burgundy and Louis of Orléans made each other's lives very miserable. The English king made good use of this and defeated the French in 1415 at Azincourt. A special event at this time was the liberation of Orléans from the English besiegers by Joan of Arc, the Virgin of Orléans. On May 30, 1431, she was burned to death by the English.

After the murder of John the Fearless, Burgundy joined the English. In 1435, with the help of the Burgundian Philip the Good, the French managed to recapture Normandy and Guyenne from the English, ending the Hundred Years' War. Under Louis XI rebellions threatened again by the nobility, who were once again supported by the Burgundian duke Charles the Bold. Louis managed to quell the revolt through secret support and bribery, and after Charles' death, Burgundy and Picardy were added to the French Empire. In 1491, through his marriage to Anna of Brittany, Brittany also became part of the French Empire. Joan of Arc, heroine of FrancePhoto: Siren-Com CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Joan of Arc, heroine of FrancePhoto: Siren-Com CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

The Valois-Burgundy antagonism, which developed into a battle between Valois and Habsburg, raged not only in the Netherlands, but also in Italy for Naples and Milan since 1494. The Italian wars were only the stakes and part of the battle waged especially by Francis I (1515–1547) against the Habsburg encirclement. At the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559), France, Italy, Flanders and Artois surrendered, but annexed Metz, Toul and Verdun, as well as Calais.

From 1562 to 1598 the country was torn apart by the religious and political party strife between the Protestant Huguenots, led by the Bourbons, and the Catholics under the Guises, between which the weak crown tried to negotiate. After the murders of Duke Hendrik de Guise (1588) and King Henry III (1589), the throne fell to the Bourbon Huguenot, Henry of Navarre. His transition to Catholicism, as Henry IV (1589–1610), took the wind from the Catholic League and in 1598 (Treaty of Vervins) managed to make peace with Spain, which had openly supported its opponents. Henry IV, king of France (1589-1610)Photo: Kaho Mitsuki CC 4.0 International no changes made

Henry IV, king of France (1589-1610)Photo: Kaho Mitsuki CC 4.0 International no changes made

The same year he granted freedom of religion to the Huguenots (Edict of Nantes) and, assisted by Minister Sully, devoted himself to the economic recovery of the country.

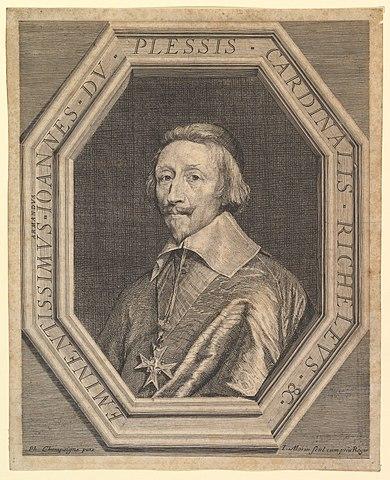

Absolute Monarchy

The period of Maria de Médici and the early years of Louis XIII were not the strongest periods in French history. This quickly changed with the decisive action of Cardinal Minister Richelieu, who eliminated the Huguenots as a political force in 1628. The nobility and the parliaments also lost much of their influence and after 1614 the States General did not even meet again. In the Thirty Years' War, Richelieu chose the Protestant powers to humiliate the Habsburgs. This enabled his successor Mazarin to claim a large part of Alsace at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

After the resistance of the nobility and the parliaments was finally overthrown, nothing stood in the way of an absolute monarchy and the struggle with the Spanish Habsburgs was carried through with vigor. The Spanish wedding of the Sun King Louis XIV even brought the Spanish throne within reach. Under Louis XIV France was the most powerful state in Europe and industry, trade and overseas colonization were vigorously promoted, among other things by organizing a powerful naval force. Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu commonly referred to as Cardinal RichelieuiPhoto: Metropoolian museum in the public domain

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu commonly referred to as Cardinal RichelieuiPhoto: Metropoolian museum in the public domain

In 1685, the Edict of Nantes was revoked, after which the Protestant Huguenots emigrated en masse and the economy, and in particular industry, was dealt a heavy blow.

The War of Devolution (1665–1669) and the Dutch War (1672–1678) provided Louis, at the expense of Spain, Franche-Comté and many border towns in the Southern Netherlands. The rest of Alsace and Luxembourg were also occupied in peacetime. The other European powers were organized by the Dutch William III, who had also been king of England since 1688. In the Nine Years' War (1688-169) and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) further plans to expand France were blocked and the balance in Europe could be maintained. Louis XIV known as Louis the Great or the Sun KingPhoto: Jebulon in the public domain

Louis XIV known as Louis the Great or the Sun KingPhoto: Jebulon in the public domain

The frivolous policies of Philip of Orléans and Louis XV followed and France even went partially bankrupt. From 1743 Louis XV ruled personally, but was guided by dubious figures such as Madame de Pompadour. Both the War of the Austrian Succession, which lasted from 1740 to 1748 and the Seven Years' War from 1756 to 1763, were unsuccessful and, partly as a result, supremacy at sea and in the colonial world was lost and taken over from England.

Thus the French influence in Canada, Louisiana and the East Indies was lost. In Europe they still managed to bring in Lorraine and Corsica. Financial reforms were carried out under the weak Louis XVI, but government debts nevertheless rose sharply. For the first time since 1614, the States General was reconvened due to this dire situation.

French revolution

Because the weak government did little to remedy the situation, the unrest among the population rose, which on June 17, 1789, declared itself a National Assembly. Feudal rights and class privileges were abolished and the rights of man and the citizen were proclaimed.

On July 14, 1789 the time had come. The people stormed and occupied the Bastille, a prison in Paris that was the symbol of absolute monarchy. This was the beginning of the French Revolution. The royal family fell and a turbulent time started. In 1791 the promulgated constitution was recognized by the king. However, he did use his veto to protect the hated nobles and un-sworn priests and the population did not accept that. Siege of the BastillePhoto: Rama Cc-by-sa-2.0-fr no changes made

Siege of the BastillePhoto: Rama Cc-by-sa-2.0-fr no changes made

The rebellious Paris city council and the new National Convention proclaimed the "first" republic between 21 and 25 September 1792. In the Convention, power was disputed between two groups: the Girondins, moderate republicans, and the radical Montagnards, with the famous figures Danton, Robespierre, Hébert and Marat. The moderates were eliminated with a lot of bloodshed by the radicals, but also quarreled among themselves, especially between supporters of Danton and Hébert.

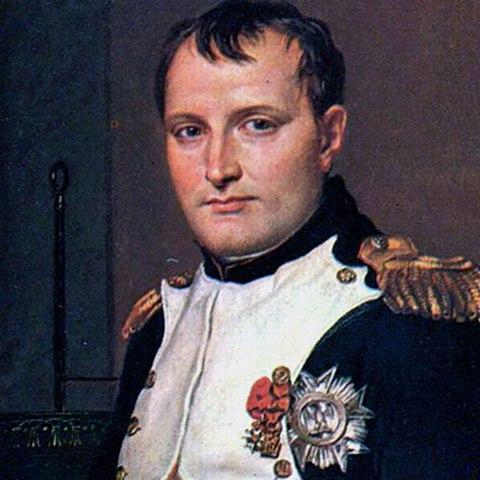

Eventually Robespierre brought them both down, but was himself killed on July 28, 1794. After this violent period, peace returned to France for a while. But from the confused situation, the Constitution of the Year III and the Directoire were born, a new assembly that tried in vain to restore order. An uprising of the Parisian bourgeoisie ensued, which was bloodily suppressed by the Corsican Napoleon Bonaparte. They also had to contend with constant Catholic and royalist revolts in the Vendée and with serious financial problems. Napoleon Bonaparte, emperor of FrancePhoto: Anderiba12 CC 4.0 International no changes made

Napoleon Bonaparte, emperor of FrancePhoto: Anderiba12 CC 4.0 International no changes made

The republic was able to defend itself well against various foreign enemies and the French territory was cleared of foreign elements by the end of 1793. People could even start thinking about spreading the principles of revolution across Europe again. The Directoire sent Napoleon to Egypt and that was the beginning of France as a colonial power in North Africa. It had also been thought to get rid of Napoleon in this way, but this failed completely.

Consulate and Empire

A coup d'état followed on November 9, 1799, after which the constitution of the year VIII was enforced and the consulate was established, where General Napoleon Bonaparte was the strong man.

When Napoleon finally came to power, he marched with his armies through a number of European countries to spread the ideas of the French Revolution. He was forced to participate in wars with ever-changing partners, the so-called coalition wars, but always with England as the main opponent. He conquered a large empire on the continent (including Italy, Spain, Germany and Poland) but would eventually encounter the English supremacy at sea, the constant resistance in Spain and the nationalism evoked by France in the rest of Europe.

In France itself, education, the judiciary and the administration were reformed and centralized, among other things by issuing the "Code Civil" and other codes. In addition, relations with the church were restored and the economy restructured. Due to all these successes, he appointed himself consul for life in 1802 and emperor for life in 1804.

However, his constant war plans met increasing opposition and after a number of significant defeats in Russia, among others, he was exiled to the island of Elba. In March 1814 he abdicated. The exile lasted only 100 days and he returned a hero. After the defeat at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, the "little general" was over and the restoration began. Napoleon was exiled by the English to the island of St. Helena in the Atlantic Ocean, where he would spend the last years of his life and died in 1821.

Restoration

After Napoleon the monarchy of the Bourbons was reinstalled and gained France had a new king, Louis XVIII, who would rule until 1824. The centralized government and legislation of the republic and of the empire were preserved, but the nobility and the clergy regained their political dominance to the detriment of the bourgeoisie. Foreign policy, in the wake of the Holy Alliance, aroused resistance. Louis XVIII, king of France and Navarra (1814-1824)Photo: Peter d'Aprix CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Louis XVIII, king of France and Navarra (1814-1824)Photo: Peter d'Aprix CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

The start of a new colonial expansion through the conquest of Algiers (1830) could not help. The authoritarian seizure of power of Charles X (1824–1830), the liberals immediately responded with the July Revolution of 1830.

July Monarchy

The bourgeois Louis-Philippe of Orléans (1830-1848) withdrew the unpopular measures of his predecessor. He accepted to rule with a constitution that placed political power in the hands of the possessing class. Since the economic depression of 1846, republican and socialist agitation has steadily gained ground. Louis-Philippe I, King of France Photo: Unknown in the public domain

Louis-Philippe I, King of France Photo: Unknown in the public domain

When the conservative Guizot wanted to forcibly oppose the demanded universal suffrage in February 1848, the people began to move. The socialist Louis Blanc and the republicans formed a provisional government. Despite the popular uprisings of May and June, the bourgeois republicans prevailed. Louis-Philippe fled to England and in France it was decided not to establish a new kingdom for the time being, but the Second Republic was proclaimed.

Second Republic

The call for a strong man brought Louis Napoleon to the presidential seat with the help of the Catholics. In return, he was expected to favor the Catholic religion. After a conflict with the Legislative Chamber over the electoral law, he rescinded this law on December 2, 1851 and engaged in a constitutional reform allowing the establishment of the Second Empire a year later on December 2, 1852, and continued as an absolute monarch as Napoleon III. In the Crimean War and the Italian campaign important military victories were achieved that put France on the map as an international power. Napoleon IIIPhoto: Rama CC 2.0 France no changes made

Napoleon IIIPhoto: Rama CC 2.0 France no changes made

Trade and industry also flourished. Because of the ambiguous attitude towards the Pope in the Italian war of freedom, the Catholics increasingly turned against Napoleon III and since 1859 he was forced to rule less autocratically. The free trade agreements with England and some other countries provoked much domestic criticism and the decline in Mexico was not forgotten either. In contrast, new colonies were founded in Algeria, Senegambia (now Senegal and Gambia), Cochin-China and Cambodia in the period 1858-1867. The lack of decisiveness in the Prussian-Austrian War in 1866 also cost him a lot of prestige. He tried to reorganize the army and amend the constitution to save face, but that was no longer successful. Following the Hohenzollern candidacy for the Spanish throne, the Franco-Prussian War broke out.

Third Republic

In this war a severe defeat was suffered at Sedan on September 1, 1870 and this led to the proclamation of the "Third Republic" in Paris and a treaty with the German Empire on May 10, 1871. In this it was agreed that France would divide Alsace and a part. of Lorraine to the Germans.

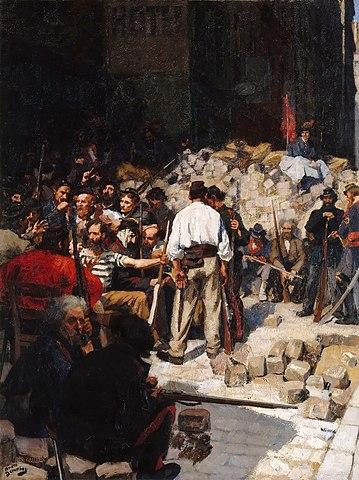

In March 1871, a more radical city council had meanwhile been elected in Paris. This so-called "Paris Commune" rebelled against the national government, which sent tropics to recapture the capital. After six weeks of urban guerrilla warfare, the uprising was crushed and some 20,000 "communards" shot or deported. In 1871 the National Assembly was also elected, in which the monarchist majority soon met with great disagreement. As a result, the Third Republic was constitutionally established in 1875. Barricade during the Paris Commune, 1871Photo: André Devambez in the public domain

Barricade during the Paris Commune, 1871Photo: André Devambez in the public domain

In 1876, the Republicans gained a majority in the Assembly and Royalist President Mac-Mahon resigned. In the last two decades of the nineteenth century, government was dominated by a number of major political scandals, including the trading of knighthoods (1887), the Panama scandal (1892-1893) and of course the Dreyfuss affair (1894-1906).

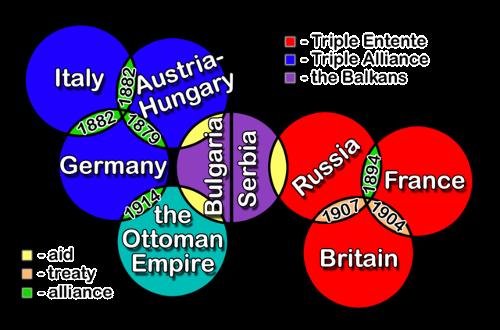

In the strongly anti-Catholic domestic politics, the separation of church and state was once more proclaimed. Social legislation got under way only slowly. Foreign policy in this period was dominated by various treaties with other major European powers. For example, there was cooperation with Germany on various African issues and after various disputes with the English, they were also approached. Due to the brutal attitude of the German Emperor Wilhelm II, France and Russia signed a two-fold alliance in 1892-1894, the so-called Duple Alliance.

In North Africa, France and Italy managed to maintain their interests, which further improved France's international position. Also with England all colonial disputes were resolved in an Entente Cordiale in 1904. The ties with Russia also became closer and eventually led to a Triple Entente with these two countries, which strengthened the position vis-à-vis Germany. As a result, France was more or less withdrawn from the First World War by the Serbian conflict between Russia and Germany. International relationships leading into World War IPhoto: Xiaphias, CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

International relationships leading into World War IPhoto: Xiaphias, CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Until 1917, France was not very successful in the fight against the Germans. At the river Marne they managed to halt the German advance. For four years the war would take place in trenches and many millions of soldiers and civilians were killed. In November 1917, the Clemenceau government came to power and under his somewhat dictatorial leadership, the defenses of France were successfully reorganized, winning victory over the Germans a year later. At the Versailles peace conference, Clemenceau wanted to completely invalidate Germany, but this plan was not well received by the Allies. France did get back Alsace and Lorraine. France suffered heavy demographic and economic losses from World War I and the government of the right-wing National Union had its hands full with its relationship with Germany and a major strike wave.

Relations with the British also became increasingly difficult. The British took a moderate stance on the issue of Germany's reparations to France. The French government approached that point of view, but the government was thereby overthrown by the nationalist Poincaré. This broke through with a unilateral occupation of the Ruhr area in January 1923 in order to force a solution. Relations with the British were further strained by the Greco-Turkish war in which France supported Turkey and Great Britain supported Greece. France, meanwhile, had a number of continental allies: Belgium, Poland and the small entente that consisted of Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Romania. Georges Clemenceau, prime minister of FrancePhoto: P. Alvarez CC 4.0 International no changes made

Georges Clemenceau, prime minister of FrancePhoto: P. Alvarez CC 4.0 International no changes made

It was not until 1924 that relations with the British were normalized again. The Ruhr policy was reversed by the new government and the British Dawes Plan on reparations was accepted. The Briand government created even more prestige in the world through the Pact of Locarno in 1925 and the Briand-Kellogg treaty in 1928. Poincaré also succeeded in stabilizing the precarious financial problems, but in contrast again had to contend with uprisings in Morocco and Syria. Before the elections, the National Union fell apart.

Tardieu's strict policy against Germany (1932) was criticized by British and exasperated Germany. For example, France was again dependent on its continental alliances and on a solid defense (Maginot Line).

The 1932 elections were won by the left, but financial difficulties, economic decline and criticism of the parliamentary system made a stable government impossible. There was fighting in Paris itself by communist, fascist and royalist groups. Prime Minister Doumergue formed a cabinet of national signature in February 1934 with a World War I hero, Philippe Pétain, and Louis Barthou. He tried to strengthen the French alliance system, including by involving Italy and Russia. He hoped in this way to isolate Hitler-Germany after the Polish abandonment of pro-Fanse politics, but was assassinated on October 9, 1934, while attempting to reconcile Yugoslavia and Italy. Not long after, Prime Minister Doumergue resigned. His successor was Laval, who was very unpopular due to his deflation policy. Pierre Paul Henri Gaston Doumergue was president of France from 1924 to 1931.Photo: Michel Huhardeaux CC 2.0 no changes made

Pierre Paul Henri Gaston Doumergue was president of France from 1924 to 1931.Photo: Michel Huhardeaux CC 2.0 no changes made

In July 1935 a united front was formed between communists, socialists and radicals against the fascist groups. Barthou's foreign policy was also subject to much criticism, including the Treaty with Rome that was concluded with Mussolini. In 1936 the Rhineland was occupied by German troops and the Locarno Treaty was canceled, which France could do nothing about, partly due to lack of support from the English.

In June 1936, Léon Blum's Popular Front government came to power. He implemented social improvements which, however, cost a lot of money and therefore resulted in strong inflation. Subsequently, the French Bank and the arms industry were put under surveillance and vigorous action was taken against fascist groups. In the Spanish Civil War, France and England remained on the sidelines with a policy of non-intervention. The radical Daladier cabinet applied a sharp deflation policy, which provoked strikes, but the economic situation improved. Léun Blum, prime minister of France (1936-1938)Photo: Anefo in yhe public domain

Léun Blum, prime minister of France (1936-1938)Photo: Anefo in yhe public domain

At the time, France was internationally behind Great Britain. Ex-ally Czechoslovakia was in fact extradited to the Germans at the Munich Conference in September 1938. After Germany's violation of the Munich Agreement, France and Great Britain gave guarantees to Poland and the Balkan states.

WWII

France declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, along with Great Britain. This happened after the German invasion of Poland. On May 10, 1940, the German troops entered France and within weeks the French defense collapsed completely. The much-vaunted Maginot Line also proved unable to withstand the German supremacy and most of France was occupied by the Germans.

On June 22, Marshal Pétain's government concluded an armistice with Germany. Pétain succeeded Paul Reynaud, who had succeeded Daladier as prime minister on March 20, 1940. Two days later, an armistice was also signed with Italy, which had invaded France on June 10. Pétain's government settled in Vichy, which was in the unoccupied part of France. After the Allies landed in North Africa in November 1942, the Germans extended their occupation over all of France. Philippe Pétain shake hands with Adolf HitlerPhoto: Heinrich Hoffman Attribution: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J28036 | Foto: Jäger, Oktober 1944

Philippe Pétain shake hands with Adolf HitlerPhoto: Heinrich Hoffman Attribution: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J28036 | Foto: Jäger, Oktober 1944

Ex-Prime Minister Laval had meanwhile taken over de facto leadership of the government in Vichy from Pétain and he strove for cooperation with the Germans. Pétain's deputy, Admiral Darlan, joined the Allies in November 1942. Pétain actually collaborated with the Germans. Outside France, General Charles de Gaulle, who had fled to England, continued the fight against the Germans with a small group of "free French". Various resistance movements arose in France itself, which worked together from May 1943 in the Conseil National dela Résistance.

In June 1944, a mighty Allied invasion force landed on the coast of Normandy and Provence in the south. The Germans could not stop the advance of the Allies. By September 1944, almost all of France was liberated and on May 8, 1945, Germany agreed to the unconditional surrender in Reims.

De Gaulle became head of a French National Liberation Committee in 1943 and returned as head of a provisional government upon liberation in August 1944. This government relied on the progressive Catholic MRP (Mouvement Républicain Openbare), the socialists and the communists. The French who had cooperated with the Germans were punished. Pétain was sentenced to death (changed to life by De Gaulle) and Laval was executed. In January 1946 De Gaulle withdrew from the government. Charles de Gaulle, president of France (1959-1969)Photo: Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-F010324-0002 / Steiner, Egon / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Charles de Gaulle, president of France (1959-1969)Photo: Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-F010324-0002 / Steiner, Egon / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Fourth Republic

In October 1946 the new constitution was approved by popular vote and the socialist Vincent Auriol became the first president of the Fourth Republic in January 1947. The period after the Second World War was characterized by a combination of great political instability and favorable economic developments. The cabinets succeeded each other in rapid succession and a number of important prime ministers of the time were Georges Bidault, Robert Schuman, Antoine Pinay and the radical Mendès-France. It was he who made the decision to come to an armistice in the war in Indochina. Pierre Mendès France, prime minister of France (1954-1955)Photo: Unknown CC 3.0 Netherlands no changes made

Pierre Mendès France, prime minister of France (1954-1955)Photo: Unknown CC 3.0 Netherlands no changes made

After the right-wing parties briefly lost their appeal, the conservatives quickly recovered after the war. In the early 1950s, Pierre Poujade organized the disaffected middle class and craftsmen, with which the organized right-wing popular protest made its re-entry into French politics.

De Gaulle, who had opposed the new constitution because of what he considered to be too weak a position of the executive power vis-à-vis parliament, founded his own party in 1947, the Rassemblement du Peuple Français. Decolonization finally brought down the Fourth Republic. In Algeria, resistance against French rule had arisen in 1954. Fearing possible negotiations with the Algerian nationalists, the French in Algeria, with the support of the army, formed a revolutionary "committee de salut public" on May 13, 1958, which advocated a government under De Gaulle. To prevent a civil war, President Coty (who had succeeded Auriol in 1954) ordered De Gaulle to form a cabinet, which, in addition to the right-wing parties, also received support from the MRP and some of the radicals and socialists (1 June 1958).

Although the Fourth Republic eventually fell to its own instability, at the European level it initiated many integration plans (Coal and Steel Community, Defense Community) aimed at promoting stability in Europe. However, these plans cannot be seen in isolation from the post-war Germany policy, with which France attempted to gain control of the Federal Republic of Germany by integrating it into Western Europe.

Fifth Republic

Now that he had come to power, De Gaulle continued his plans for constitutional reform. On September 28, 1958, more than 80% of the voters voted in favor of the new constitution that gave the president a lot of power and authority. In addition, the new Gaullist party Union pour la Novelle République was given the largest fraction in the national assembly. De Gaulle himself was installed as president on January 8, with Michel Debré as prime minister who was succeeded in 1962 by the future president Georges Pompidou. Michel Jean-Pierre Debré, first prime minister of the Fifth French RepublicPhoto: Eric Koch / Anefo in the public domain

Michel Jean-Pierre Debré, first prime minister of the Fifth French RepublicPhoto: Eric Koch / Anefo in the public domain

The situation in Algeria caused right-wing politicians and soldiers to revolt. However, this coup d'état in the Algerian capital Algiers on April 22, 1961 failed. On April 8, 1962, more than 90% of the population voted in favor of Algeria's independence in a referendum. Algeria eventually became independent after a bloody colonial war after an amendment to the constitution on October 28, 1962. After elections in March 1967, the Gaullists and their allies still retained a narrow majority; De Gaulle's term of office was extended by seven years in December 1965.

The De Gaulle period was generally marked by the restoration of France's position as an independent and influential country among the great nations of the world. Moreover, De Gaulle ultimately wanted a large Europe from the Atlantic Ocean to the Urals, and this required the influence of the United States to be reduced. As a result of this thesis, France withdrew its troops from NATO authority in 1966 and all NATO bases were cleared. They also wanted to become a nuclear power and therefore did not sign the non-proliferation treaty. Great Britain was twice banned from the EEC, but relations with Germany were normalized, as were those with Russia and other Eastern European countries. The French got along well with the Arab countries, but that had repercussions on the relationship with Israel. In the second half of the 1960s, dissatisfaction arose among students and workers with the policy of the government. In May 1968, the famous uprising broke out in Paris, which would last only a month after promises of wage increases for the workers. Civil unrest in May 1968 in FrancePhoto: Andre Cros CC 4.0 no changes made

Civil unrest in May 1968 in FrancePhoto: Andre Cros CC 4.0 no changes made

In the elections held in June, the Gaullists made great gains and formed a front against the socialists along with the independent republicans and other independents.

1970s and 1980s

In April 1969, De Gaulle resigned because his proposals regarding reforms, including a new regional division, had been rejected. The presidential elections brought a victory for the Gaullist Georges Pompidou. On domestic territory, Pompidou aimed for rapid industrialization, in foreign policy he followed the De Gaulle line, although less rigidly. For example, he cooperated in the accession of England to the EEC and more often took positive positions at NATO meetings. Georges Pompidou, 19th president of France (1969-1974)Photo: Eric Koch / Anefo, CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Georges Pompidou, 19th president of France (1969-1974)Photo: Eric Koch / Anefo, CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

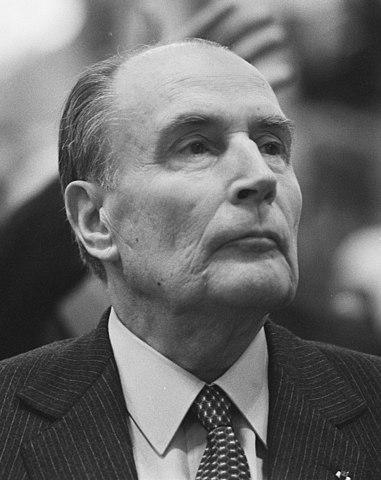

The March 1973 parliamentary elections were won by the cooperating socialists and communists, but the governing parties retained the majority. The Left also formed a coalition in the death of Pompidou (April 2, 1974) and the subsequent presidential elections. These were won in May 1974 by the Minister of Finance and Economy, the independent republican Giscard d'Estaing.

He defeated the socialist leader François Mitterrand with very little difference. The Gaullists at that time had no new candidate for the presidency and therefore gave their support to the Republican Giscard. Jacques Chirac became Prime Minister of a cabinet of Gaullists and Republicans. In 1976, the president fired Chirac and appointed Raymond Barre prime minister.

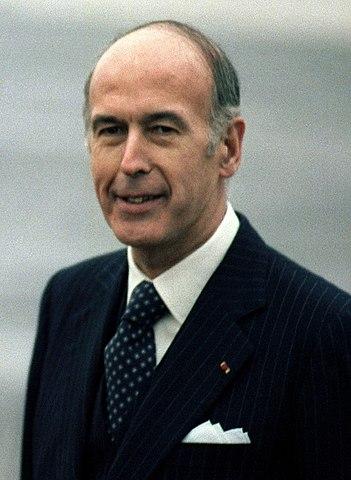

Under Giscard, the policy pursued by his immediate predecessors was broadly continued. In foreign policy, the pursuit of a strong Europe controlled by France and the Federal Republic of Germany, independent of the United States, was maintained, as was the pro-Arab stance in the Middle East. Valéry Marie René Georges Giscard d'Estaing, 20th president of France (1974-1981)Photo: White House Staff Photographers in the public domain

Valéry Marie René Georges Giscard d'Estaing, 20th president of France (1974-1981)Photo: White House Staff Photographers in the public domain

In former French Africa, France continued to be represented by the presence of military troops and advisers, while its financial and economic influence was further increased. Inland, Giscard had to deal with separatist movements in Corsica and Brittany, among others. In May 1981, Giscard was surprisingly defeated by the socialist presidential candidate François Mitterrand.

He became the country's first socialist president since the establishment of the Fifth Republic in 1958. After the parliamentary elections in June, a government of socialists (PS) and communists (PCF) under P. Mauroy tried to improve the nationalize the French economy by nationalisation. In June 1982, disappointing results forced them to water down progressive economic policy. Under L. Fabius, the communists were no longer part of the government. After UDF – RPR, led by Jacques Chirac (RPR), had won the parliamentary elections in March 1986, the Fifth Republic was confronted with a political variant unknown in the history of France, the "cohabitation": a prime minister and a president of different political colors. After Mitterrand had again won the presidential election from Chirac in May 1988, after the parliamentary elections of June 1988, a socialist government under the leadership of M. Rocard was re-established. Jacques Chirac, 21st president of France (1995-2007)Photo: Rob Croes / Anefo in the public domain

Jacques Chirac, 21st president of France (1995-2007)Photo: Rob Croes / Anefo in the public domain

In the eighties, the following were particularly noticeable: the shrinking electoral base of the communist party and its political influence, the rise of the extreme right in the form of Jean-Marie Le Pen's National Front and the rise of the Greens, Les Verts, who have been represented in the European Parliament since June 1989.

The nineties

for the first time, a woman became Prime Minister of France (Édith Cresson) in 1991. Unpopular measures, including premium and tax increases, were devastating for her popularity and she was already succeeded in April 1992 by Pierre Bérégovoy. He stepped down as Prime Minister after the socialist defeat in the elections of 12 March 1993 and was succeeded by Édouard Balladur. In May the disappointed Bérégovoy committed suicide, partly as a result of the failure of his economic program. In July 1993 the bad economic situation led to attacks by speculators on the French franc. As a result, the French franc was effectively forced out of the European Monetary System. The Balladur government faced numerous corruption scandals in 1994 that forced some ministers to resign. Édouard Balladur, prime mister of France (1993-1995)Photo: Dutch National Archives CC 3.0 Netherlands no changes made

Édouard Balladur, prime mister of France (1993-1995)Photo: Dutch National Archives CC 3.0 Netherlands no changes made

In the presidential elections of May 1995, Jacques Chirac, leader of the Gaullist RPR and mayor of Paris, first left his party colleague Balladur behind and also won in the second round against the socialist candidate Lionel Jospin. Jean-Marie Le Pen of the far-right National Front won 15% of the vote. After initially delivering on some of Chirac's election promises, the popularity of Prime Minister Juppé, who advocated a punitive austerity policy, declined rapidly.

A wave of strikes paralyzed public life in late 1995 and mass strikes continued in October and November 1996 in the railways, aviation, education and other government departments. Truck drivers started blockades to improve their working conditions, which demand the government partially met. Meanwhile, economic growth slowed and unemployment reached a post-war record.

In 1995 Paris was shaken by a number of terrorist attacks by the Algerian fundamentalist-Islamic organization GIA and Corsica was the subject of a large number of bombings in 1995 and 1996 by various nationalist movements.

Former president François Mitterrand died in early January 1996. In municipal elections in February 1997 in the southern French town of Vitrolles, the Front National won an absolute victory, placing the fourth southern French city in the hands of the far right, while Nice is ruled by a kindred spirit of Le Pen. Jean-Marie Le Pen, chairman of Front National (1972-2011)Photo: Kenji-Baptiste OIKAWA CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Jean-Marie Le Pen, chairman of Front National (1972-2011)Photo: Kenji-Baptiste OIKAWA CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In the spring of 1997, President Chirac called early elections in the hope of strengthening the position of the Juppé government. In two rounds of elections, the socialists led by Jospin and their allies won a major victory on June 1, taking 282 of the 577 seats in the National Assembly.

In 1995, French nuclear tests on Mururoa Atoll in the South Pacific provoked fierce protests, especially from Australia, New Zealand and Japan. Following the trials, France signed the Rarotonga Treaty for a Nuclear Weapons Free Zone in the South Pacific in early 1996. In June 1996, Defense Minister Millon announced at a biannual meeting of his NATO colleagues in Brussels that France wanted to contribute to a "new" NATO with a distinct European defense identity.

In the run-up to the European summit in Dublin in December 1996, disagreements arose between France and Germany about the Stability Pact, which should ensure budgetary discipline among the participating countries after the entry into force of EMU. Paris argued for more political freedom: wider margins and less autonomy for the European Central Bank.

With the early parliamentary elections in May / June 1997, President Chirac aimed to create additional time to implement, if necessary, painful measures necessary to meet the criteria for participation in EMU. Chirac gambled and lost: the winner was the Socialist Party (PS) led by Lionel Jospin, who formed a coalition with the Communists (PCF) and the Greens. Initially, the popularity of the new coalition government-Jospin was great, but was soon put to the test by, among other things, opposition from the trade unions against restructuring in social services and that of secondary school students who took to the streets en masse in October 1998 to increase their resources. to demand secondary education. Lionel Jospin, prime minister of France (1997-2002)Photo: User:EdouardHue CC 4.0 International no changes made

Lionel Jospin, prime minister of France (1997-2002)Photo: User:EdouardHue CC 4.0 International no changes made

The introduction of a 35-hour working week in 1998 to create more jobs did not help the relationship between government and employers and in 1999 Jospin's position was further weakened when Finance Minister Dominique Strauss-Kahn, after Jospin, was the most powerful man in the government announced his resignation on November 2, after being accused of corruption.

21st century

In September 2000, French voters voted in favor of a constitutional amendment reducing the presidential term from seven to five years; 73% were in favor of the change. The parliamentary right came to power in 2002 after a surprisingly passed Presidential election, in which the extreme right succeeded in eliminating the socialist presidential candidate Jospin in the first round. The result was widespread support for the re-election of President Chirac, who faced Le Pen as a candidate for the National Front. Jean-Pierre Raffarin, prime minister of France (2002-2005)Photo: Claude TRUONG-NGOC CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Jean-Pierre Raffarin, prime minister of France (2002-2005)Photo: Claude TRUONG-NGOC CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Given the circumstances, the government and Prime Minister Raffarin, appointed by President Chirac, proceeded cautiously, even too cautiously according to some commentators. Social peace was wanted at all costs, because it was considered essential for maintaining consumer confidence and thus employment. Necessary reforms such as tax reform (in France still no tax is levied at source) and liberalization / privatization of semi-public enterprises and reform of the health sector were pushed aside. Instead, the government focused on issues such as decentralization, street security and increasing defense spending. Still, the first year of the Raffarin government ended with a relatively positive balance before the summer of 2003. Successes were mainly achieved in tackling crime (less crime) and traffic problems (fewer road casualties).

In the summer of 2003, the tide began to turn. In July, the government's proposal for an institutional reform for Corsica was rejected by almost 51 percent no votes. This put the government's decentralization legislation under greater pressure. There was also unexpectedly a lot of resistance from the population against the changes to the pension system, against the decentralized recruitment of support staff in the education sector in the context of the decentralization policy and against the tightening of the benefit criteria for employees in the theater and festival world. On top of that came the catastrophic heat wave in August 2003 that claimed more than 15,000 victims.

Then the government went into free fall in terms of popularity: the press talked about the beginning of the end. Although it seemed at the beginning of 2004 that the government was regaining confidence - partly because of the hard stance in favor of the non-denominational character of the French state (prohibition of the Islamic headscarf) - this was not translated in the regional elections of 21 and March 28, 2004. The left got 13 percentage points more than the right (50.3 versus 36.8 percent). The left came to power in all regions (including the hitherto impregnable strongholds of the right). With the exception of Alsace and Corsica. As a result, part of the government team was replaced and the Raffarin III government took office.

In a televised address, President Chirac had placed the renewed Raffarin III government in the context of the need for structural reforms in France. Reforms and social justice had to go hand in hand. France, according to the president, should have a real social dialogue. Reforms should preferably be broadly supported. At the same time, state finances need to be restructured. The Raffarin III government statement was in line with the president's wishes.

On Sunday 29 May 2005, the French people voted en masse in a referendum against the Constitutional Treaty for the European Union. Chirac subsequently appointed Dominique de Villepin as prime minister and reappointed Nicolas Sarkozy as "ministre d'Etat" (thus number two in the government by protocol) to the position of Minister of the Interior. On the recommendation of De Villepin, the government team has been drastically reformed and greatly reduced in size (all state secretaries have been removed).

On June 9, 2005, Prime Minister De Villepin made the government statement in the Assembly. The announced measures related in particular to socio-economic policy: "Get France back to work" was the central message. The cost of the package of measures is estimated at EUR 4.5 billion. The 2006 income tax cut (President Chirac's announcement in July 2004) has been suspended for the time being. De Villepin will not implement the employment package through laws, but through "ordonnances". He bypasses lengthy procedures (and amendments) in Parliament. Opposition, of course, strongly opposed this alleged "authoritarian" form of government. Dominique Villepin, prime minister of France (2005-2007)Photo: Georges Seguin CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Dominique Villepin, prime minister of France (2005-2007)Photo: Georges Seguin CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

The French press speaks of the “after days of Chirac”. There is clear unrest within the ruling party UMP. The younger generation of right-wing politicians wants to prevent the left from taking over the Elysée again in 2007 and is therefore trying to take more control of the UMP in its own hands. It is also recalled that the UMP was supposed to be a breakthrough party, with all kinds of movements and not just Gaullists or Chirac supporters. Behind this pursuit of blood group recovery, one can see the opening of the first skirmishes over Chirac's succession. De Villepin's appointment coupled with Sarkozy, both very ambitious and possibly in the running for the next presidency, raises questions about the team spirit of the new administration.

The socialists have also been severely affected by the rejection of the Constitutional Treaty. Although the official party line mandated support for the treaty, the second man of the PS, Laurent Fabius, led an active no campaign. After the French 'no', party leader François Hollande therefore had no other choice than to expel Fabius as a member of the board. The division within the PS is now considerable. The party congress of the PS has been brought forward half a year to the autumn of 2005 in order to repair the debris before the campaign for the 2007 presidential election starts.

Nicolas Sarkozy has been president since May 16, 2007. The president has relatively great power, because he is head of state and government leader. In July 2008, France will hold the presidency of the European Union for six months. In October 2008, the magnitude of the credit crunch becomes noticeable and in February 2009 the government is pumping billions into the economy. In March 2010, the governing parties suffered a major loss in regional elections. In June 2010, the government announced drastic cuts to reduce the national debt. Nicolas Sarkozy, 23rd president of France (2007-2012)Photo: Richard Pichet CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Nicolas Sarkozy, 23rd president of France (2007-2012)Photo: Richard Pichet CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In September 2010, after the National Assembly of France, the Senate in France also approved the burqa ban. When the law goes into effect, all face-covering clothing will be banned in public areas. Women who wear face-concealing clothing on the street or in public places can be fined 150 euros by law. In May 2012, the socialist Francois Hollande takes office as the new president. In 2013, France sends an intervention force to the former colony of Mali.

In March 2014, Manuel Valls becomes the new prime minister, after a rise of the National Front. The front also won nationally in the European elections in May 2014. At the end of 2014, the work pilotage rose to a record high. The year 2015 is dominated by terrorist attacks on French territory by the Islamic State. In January 17 victims fell, mostly employees of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. In November, 130 people were killed in various attacks in Paris.

In February 2016, the clearing of the "jungle" of Calais, a large camp with illegal immigrants who want to make the crossing to Great Britain, begins. On July 14, 2016, Islamic State strikes again when a truck crashes into a crowd on National Day, killing more than 80. In May 2017, center candidate Emaunuel Macron wins the French presidential election against the ultra-right Marine Le Pen. His movement La Republique en Marche won the absolute majority in parliamentary elections in June. Emmanuel Macron, 25th president of FrancePhoto: Kremlin.ru CC 4.0 International no changes made

Emmanuel Macron, 25th president of FrancePhoto: Kremlin.ru CC 4.0 International no changes made

End 2018 major nationwide "yellow-vest" protests take place at attempts to curb fossil fuel use through price hikes turn violent, prompting a partial government climb-down. Protests continue into 2019, In july 2020 President Macron appoints Jean Castex prime minister, after Edouard Philippe resigned in the wake of a poor showing for the governing La République En Marche! party in local elections. In Conflans-Sainte-Honorine, a suburb to the northwest of Paris, a history teacher who recently showed caricatures of the prophet Mohammed was beheaded in the street. The eighteen-year-old Chechen culprit was shot dead by the police. Jean Castex, prime minister of France since 1 july 2020Photo: Florian DAVID CC 4.0 International no changes made

Jean Castex, prime minister of France since 1 july 2020Photo: Florian DAVID CC 4.0 International no changes made

2021 and early 2022 will be marked by the upcoming elections in which Macron will face Valérie Pécresse of Les Républicains, Marine Le Pen of Rassemblement National and Éric Zemmour of Reconquête, among others. Emmanuel Macron wins French presidential election in April 2022. This will allow him to begin a second five-year term in office.

Sources

BBC - Country Profiles

CIA - World Factbook

Heetvelt, Angela / Picardië : Nord-Pas-de-Calais

ANWB

Picardie : Somme-Oise-Aisne

Lannoo

Wikipedia

Copyright: Team The World of Info