ARGENTINA

History

History

Cities in ARGENTINA

| Buenos aires |

History

Pre-Columbian Period

About 6000 years BC. people already lived in Argentina. Objects indicating this have been found in the provinces of Córdoba and San Luis. Approx. 5000 years BC. the first agricultural communities existed and 1000 years later the first cultures and residential communities arose. Even on the southern and inhospitable Tierra del Fuego, remains that are almost 7,000 years old have been found. They were hunting nomads who took advantage of the many animals that thrive in the warm humid climate.

The first real indications of residential communities and peoples are ceramics, stone objects and menhirs, found in the provinces of Jujuy, San Juan and Tucumán, among others.

In the north and east of Argentina, agricultural communities developed that lived on beans, sweet potatoes and especially maize. People in the northwest were already raising llamas and using the wool to make clothes. The center of the country also underwent an agricultural development, but Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego continued to depend on hunting, so that cultural development lagged behind.

In the first centuries after the beginning of our era there was already talk of building houses, the use of bronze and copper objects and even an ingenious irrigation system

Around the year 1000 to 1480, Argentina was divided among the main Indian peoples in the following way:

Northeast: Diaguitas

Middle: Huarpes

Pampas and along the coast: Querandies and Puelches

Chaco area: Tobas

Lake District: Araucanians

Patagonia: Tehuelches

Tierra del Fuego: Onas, Yaghanes, Selknam and Haush

In 1480, northeastern Argentina was invaded by the Incas, who were looking for silver and gold. However, they found almost nothing and did not get further than the province of Salta in the far north of Argentina.

Spanish rule

In 1516, the adventurer Juan Díaz de Solis Rio docked at the Rio de la Plata, but unfortunately he was murdered and then eaten by the Indians. Then it was the Venetian Sebastian Cabot who sailed along the banks of a wide estuary, which he called the Rio de la Plata, and he too was looking for silver.

In 1536 the first Europeans came ashore and it was Pedro de Mendoza who founded the settlement of Santa Maria de los Buenos Aires (the holy Mary of the clean air) on the Rio de la Plata. The village was destroyed by the Indians a few years later and Mendoza fled to the north. Approx. 40 years later, the definitive Puerto Santa Maria de los Buenos Aires was founded by Juan de Garay.

From Bolivia another group of Spaniards entered northern Argentina and they were much more successful. Within a few decades, the entire north was colonized and cities such as Mendoza (1561), San Juan (1562), Tucumán (1565) and Córdoba (1573) emerged. This colonized area was ruled on paper from Lima, Peru, but in reality the influence of the Spanish was negligible. It was mainly the Jesuit missionaries who benefited from this. From 1609 onwards they founded so-called "reducciónes" in the northeast, mission posts that worked well with the Indians and tried to protect them against the large landowners, who needed many slaves for their plantations. This created posts that were economically completely self-sufficient. Such communities also sprang up in the northwest, with the big difference that they were set up by the local "government". The Indians lived in such an "encomienda," but in fact they just led a slave life. Many Indians did not last long; Within a few decades, the hard work and many diseases that broke out decimated the Native American population, making the encomiendas basically redundant. From that time on, the encomiendas were more or less replaced by "haciendas", farming communities that worked the land independently and later also kept livestock in so-called "estancias". The owners were often Spaniards born in South America, the Criollo's, and by Mestizos, who were half Spaniard, half Indian. They grew tobacco, sugar cane, corn and cotton.

In 1767 the position of the Jesuit missions was radically changed by a decision of the Spanish King Philip III. According to Philip, the Jesuits undermined Spanish authority and were ordered to return to Spain. The reality, however, was slightly different. It mainly concerned a battle between the landowners and the church, which was almost as powerful and rich.

The Jesuits had no resources or power to stay, and they left Argentina in their thousands. This immediately ended the many reducciónes, all of which were destroyed. In 1777 Spain decided that Rio de la Plata would get a viceroy who would be directly under the Spanish king. Argentina therefore no longer fell under the Peruvian viceroy.

It was important that trade with Spain was now allowed from Buenos Aires. Until then, Buenos Aires had remained a relatively insignificant smuggling port since it was founded in 1580. Two other cities, Tucumán and Córdoba, were already much more important to the Northern Argentine region. At that time, Tucumán was the center of trade, also for exports to neighboring countries, and Córdoba was the intellectual center with universities and colleges.

Argentina independent

History Museum Buenos Aires ArgentinaPhoto: Georgez in the public domain

History Museum Buenos Aires ArgentinaPhoto: Georgez in the public domain

From this time on, Buenos Aires became the most important trading city, both for transit to Bolivia and Peru and for export to Europe. With the rise of Napoleon at the beginning of the nineteenth century, Spain slowly lost its grip on the colonies, also because the Spanish fleet was in decline.

Spain's powerful position was soon taken over by the British who had taken control of much of the trade to South America. Of course they also had their eye on Argentina and of course especially on Buenos Aires. In 1806 Buenos Aires was occupied by the British, but as early as 1807 they were expelled by a small army of insurgents that were passionately supported by the population. Spain had meanwhile been taken by Napoleon and the Criollo's increasingly longed for independence from Spain. In the end, it was Manuel Belgrano, Bernardino Rivadavia and Mariano Moreno, three Criollo's who, influenced by the French Enlightenment and the French Revolution, took the initiative for an independent state.

On May 25, 1810, several hundred civilians proclaimed a provisional junta of the province of Rio de la Plata, which would take over the authority of the Peruvian viceroy. The landowners (estancieros) naturally wanted to keep their lands and problems soon arose between the so-called Unitarians, who wanted a strong central authority, and the Federalists, the leaders of the provinces and landowners who did not want to submit to the central authority in Buenos Aires. Elsewhere in South America, the Spanish-minded tried to re-take Bolivia, and Uruguay and Paraguay were also very unsettled.

Independence

House of independance Tucuman ArgentinaPhoto: Fulviusbsas CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

House of independance Tucuman ArgentinaPhoto: Fulviusbsas CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

On July 9, 1816, a constitution was passed and independence was declared in Tucumán. The only problem was to expel the Spaniards from Argentina for good. Under the Argentinian General José San Martin, the Spaniards were defeated in 1817 and he successively liberated Chile and Peru, without receiving much recognition. In the interior, an internal struggle broke out between the federalist gauchos of the countryside and the unionist capital cities. In 1829, the caudillo (powerful leaders of a province or region) Manual de Rosas came to power with the help of the gauchos. De Rosas's reign would be one of the bloodiest in Argentine history. Not only advocates of central authority, the Unitarians, Indians and Gauchos were massacred; fellow caudillos were also slaughtered by the secret police, the Mazorca.

The opposition, led by some intellectuals, got the help of the caudillo general José Urquiza, and with a volunteer army he managed to defeat De Rosas' army in 1852. In 1853 a new constitution was passed and Urquiza became Argentina's first president. A period of construction, rest and bloom followed. Not even a bloody war with Brazil and Uruguay against Paraguay could stop modernization. Thanks to this war, Argentina even gained territory in 1870: the provinces of Chaco, Formosa and Misiones.

Under President Sarmiento, who came to power in 1868, the education system was revamped and the pampas' agriculture and ranching were given enormous impetus. Refrigeration systems, the invention of barbed wire and railroad transportation even allowed Argentina to consider exporting meat to the United States and Europe. One of the problems, however, was the labor shortage, but this was solved by the arrival of large groups of European immigrants. Furthermore, the Indians had to be expelled from the future pastures. That problem was solved by General Julio Roca, who liquidated Indians on a large scale in 1879. In this bloody way, the large landowners gained approximately 400,000 km2 of pampas land within a few months. In less than sixty years, the population of Argentina rose from 800,000 in 1851 to eight million in 1910. At that time, the population was very diverse and three-quarters were non-Argentine. The European workers were assigned to certain areas or activities in a kind of colonies. Italians, Spaniards and English, for example, often worked in the ports, French and Swiss farmers in Mesopotamia and Germans in the forests of the province of Misiones. Real power in Argentina was in the hands of the landowners, the grain and cattle farmers, the financial elite, and the meat and wool exporters. Argentina was doing very well economically at that time and the country was for some time one of the ten richest countries in the world.

The First World War had major consequences for the Argentinean economy. The European sales market largely disappeared, as a result of which people could no longer pay their debts and the country fell into a financial crisis. Predictably, the middle class immediately revolted as it was hit hardest by the crisis; they demanded more freedom and openness. This middle class consisted largely of European immigrants who, under the leadership of Leonardo Alem, founded the Unión Civica Radical, the Radical Civic Union.

In 1916 the first free general elections were won by the radicals and Hipólito Yrigoyen was elected president. After the First World War, Argentina returned to full economic importance; America and Europe again needed a lot of grain and meat, and so started another period of prosperity and relative prosperity that lasted until the late 1920s. President Alvear (1922-1928), who restored the gold standard for the country, was succeeded by Irigoyen.

In 1930 Argentina also had to deal with the international economic crisis and the conservative forces saw their chance and staged a coup. Analogous to the situation in Europe, fascist and nationalist ideas also emerged in Argentina. Irigoyen was succeeded by General José Felix Uriburu and then a choice of presidents followed until the end of World War II, successively Agustín P. Justo, Roberto Marcelino Ortiz, Ramón S. Castillo, Pedro Pablo Ramirez and Edelmiro Julian Farrell.

Era Perón

President Castillo kept Argentina out of the war, provoking the anger of the United States. It was only under President Ramirez that Argentina broke diplomatic relations with Germany and at the last moment war was declared on Germany and Japan. However, the ideas of the European dictators were followed with interest during the war. Juan Perón, an army officer, was one of those figures who had political sympathies for the socio-economic policies in Germany and Italy. To analyze fascism he was stationed in Italy to see it with his own eyes.

When he came back he knew exactly what Argentina needed. First of all, he became Deputy Minister of Labor and in 1943 and 1944 he managed to gain many supporters among Spanish and Italian emigrants, port and agricultural workers. It became increasingly clear that Peron would one day become the leader of Argentina; in 1944 he became vice president and secretary of war, making him a powerful man in the Farrell administration.

A temporary setback followed in 1945 when he was arrested after another military coup. A young radio announcer heard this and called on the population via the radio to protest against the state of affairs. Hundreds of thousands of people gathered in Buenos Aires in October 1945, and with the help of the army and a major strike, Perón was recalled, and in 1946 he even became president. He married the radio announcer Eva Duarte, who from then on would be called Eva "Evita" Perón, and became world famous. In 1947, Perón founded his own party, the "Partido Paronista", under the motto "justicialismo" (justice).

After the Second World War, Argentina was doing well, and great progress was made both economically and socially. Good social laws for workers were drawn up, trade union wishes respected and all major companies were nationalized. The reform of the outdated industry was also successful. Perón's rule was totalitarian, almost dictatorial, and it was taken for granted. However, he managed to restore national unity and, partly because of his wife Eva, gained great popularity abroad as well.

In 1951, Perón was re-elected by a large majority as president of Argentina. From that time on, the economy suffered the first blows. Rapidly rising government expenditure, crop failures and sharply falling grain prices on the international market caused major economic problems. Opposition to Perón grew rapidly, and Evita Perón's death came at a very bad time. Strikes and demonstrations followed and in 1955 Perón decided to resign under pressure from the military, the church and the elite. He then fled to Paraguay and from there as an exile to Spain.

Dictators and Coups

From 1955 to 1973 it was an administrative chaos in the country. Military coupes and civilian presidents alternated, but Peronism proved not to be banished from society. The underground left Peronist movement "Montoneros" even started an armed struggle against the military, after which a witch hunt for the Peronists was unleashed. On September 23, 1955, Eduardo Lonardi became president, succeeded less than a month later by General Pedro Aramburu. At the time, economic policy was aimed at fighting inflation, lifting the state monopoly and attracting foreign capital.

In 1958, the radical Arturo Frondizi was elected president with the support of communists and Peronists. Frondizi's foreign policy (he sought rapprochement with the United States) aroused a lot of resistance and in 1959 alone he faced 25 government crises. In 1962 the Peronists were allowed to participate in the elections again and they achieved a great triumph. However, this led to the departure of Frondizi, after which a period of crisis ensued and the military was in effect in control. They appointed José Maria Guido president in March 1962 and the hold of the army was increasing; for example, the communist party was banned.

In July 1963, the radical Arturo Illia was elected president. He proclaimed a policy of economic nationalism and called on the armed forces to settle their differences. In December 1964, ex-president Perón made an attempt to return to Argentina, but he was not admitted. His wife, Isabel Perón, was admitted, after which she tried to take over the leadership of the Peronists in January 1966. In the elections for the Chamber of Deputies, the Peronists with their new party Union Popular, again came out as the strongest party.

On June 28, 1966, President Illia was deposed and succeeded by General Onganía. Onganía banned all political parties and gave top priority to economic development. The social peace that was desperately needed for this led to a certain collaboration with the Peronist trade union federation CGT. In 1969, a major popular uprising started in the city of Córdoba, but was bloody suppressed by the military. The call for Perón's return grew louder and the military leader of the time, Lanusse, Onganía's successor, responded. He called for presidential elections, Perón was even allowed to return to Argentina and the ban on the Partido Justicialista was lifted.

However, his return was not such a success. Fighting broke out between various Peronist groups and the secret police, resulting in hundreds of deaths. However, this did not prevent Perón from being re-elected president on September 23, 1973 with his wife Isabel Perón as vice president.

At the time, however, Perón was no longer physically and mentally up to his difficult task, and both left and right groups committed acts of terrorism, and murders and kidnappings were the order of the day. He was also confronted with a strong division in the Peronist movement between left and right groups. In 1974, Perón died and his wife Isabel became president under a state of emergency. Real government, however, was in the hands of the Minister of Welfare, López Rega. He founded Argentina's Anti-Communist Alliance, the AAA. Everything left was now outlawed and in a few years thousands of people lost their lives in the battle between the left-wing guerrilla and the AAA. The economic situation was very bad during this time, corruption was rampant, so the military thought it was high time to carry out another coup d'état, the fifth time in 40 years. In the meantime, unions, politicians and soldiers managed to persuade the president to resign López Rega. On March 24, 1976, Isabel Perón was deposed and arrested by the military. She was released in June 1981, after which she too went into exile in Spain.

Videla's military rule, 1976-1983

A junta of three soldiers came to power, Emilio Messera and Orlando Agosti and General Videla as president. The plans for reconstruction and the fight against "terrorism" soon turned out to be empty talk. Anyone who had some left-wing or progressive ideas was suspect, could just be arrested and his life was no longer safe. In this fairly short period, according to human rights organizations, about 30,000 people disappeared; in 1984 an official commission of inquiry documented the abduction by military personnel of 8,960 people.

In 1978, the Montoneros were defeated in the so-called "dirty war" (guerra sucia) and the united resistance was broken. In 1978, when the FIFA World Cup was held in Argentina, the "Foolish Mothers" of the Plazo de Mayo made their name for the first time. They soon became world famous and still walk in the square to get more information about their missing children or family. The leader of one of the human rights organizations, Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1980.

The military had a plan to get the economy back on track, but it failed completely. The many loans taken out by the government made the external debt too high. The international economy continued to decline and the pressure on government increased. On March 29, 1981, Videla was succeeded by General Roberto Viola, but already on December 22, 1981, the extreme nationalist General Leopoldo Galtieri took over the presidency.

It was also he who declared war on England in March 1982 on the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas). This archipelago had been conquered by the English from the Argentines since 1833 and has been a point of contention ever since. The Argentines expected no response from the British, but the British government decided to send an expeditionary force. On June 16, 1982, the Argentine commander in the Falkland Islands, General Mario Menéndez, surrendered. Approx. 800 Argentine and 200 British soldiers were killed in the war. Due to disastrous economic policies and the defeat in the Falkland Islands, General Galtieri resigned as President and Commander in Chief of the Army and was succeeded on June 22, 1982 by General Reynaldo Bignone, who was tasked with arranging the return to civilian rule.

Period Alfonsín

The general election of October 30, 1983 was won by the Radical Civil Union of Raúl Alfonsín, who was installed as the new civilian president on December 10. After nearly eight years of oppression and terror, the population had high hopes for the new president. However, he was unable to keep his promise of "a hundred years of peace and prosperity", also because Argentina was in an economically dire situation. The investigation into the thousands of disappeared persons, entitled "nunca mas = never again", was also very difficult. Generals like Videla and Galtieri were convicted, but not everyone was arrested. Alfonsín was under heavy pressure from the military, who wanted absolutely no massive convictions and were always ready to commit a new coup.

In the Alfonsín period, the economy went badly, inflation soared and the World Bank demanded the borrowed money to be paid back. In addition, the president had to deal with a bureaucratic civil service that consumed almost the entire budget. In 1985 Alfonsín announced a price freeze, combined with severe budget cuts. Furthermore, the peso, the national currency, was replaced by the austral, but all these measures barely worked. The criticism of Alfonsín increased rapidly and it was therefore not surprising that he lost the presidential election of May 14, 1989 with flying colors. The elections were won by ex-governor Carlos Menem of the province of La Rioja and member of the Partido Justicialista, the Peronist party. In April 1987 and in January and December 1988 some army units revolted, but this ultimately had no serious consequences

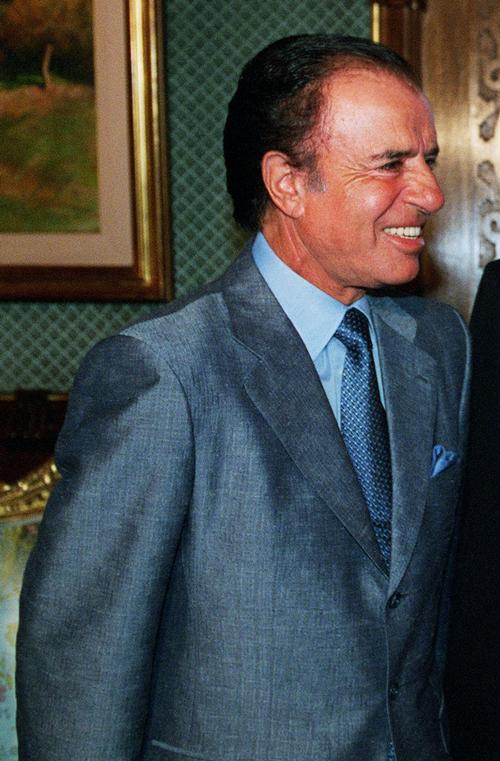

Period Menem

Under Carlos Menem, Argentina's economic recovery was somewhat better. The cuts worked out well and the hyperinflation came to an end. Military pressure was greatly reduced by granting amnesty to suspected soldiers. That the Peronist principles were largely abandoned was taken for granted by the population. For example, the free market economy was embraced and the peso, the national currency, returned. Furthermore, import restrictions were sharply reduced and many large state-owned companies were nationalized. In the early 1990s, Argentina and Great Britain restored diplomatic relations, although the Argentine did not give up claims to the islands. In December a mutiny of a number of soldiers was put down by pro-government troops. In Dec. In 1990 Menem granted amnesty to the members of the former juntas and some other senior officers and civilians, who were sentenced in 1985 to long prison terms for human rights violations during the military dictatorship. They included ex-presidents Videla and Viola.

From 1994 there was no more inflation and the country became more and more economically stable. Unfortunately, it was mainly the rich who benefited from this, while the weak groups in society continued to suffer from great poverty, also due to the increasing unemployment as a result of the privatization of state-owned companies. In 1995, the Argentinean economy was hit by the financial crisis in Mexico, but Argentina recovered quickly from this situation, achieving very high economic growth year after year.

Menem was involved in many scandals during his first reign, including corruption through the appointment of friends and acquaintances to important posts. He also managed to push through a constitutional amendment that made it possible to get a second term as president. The May 1995 presidential elections were still won by Menem, but the 1997 midterm elections for half of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies were lost by the Peronists and they lost the majority in parliament at that time. In 1998 Menem stated that he would not run for the 1999 presidential election.

Fernando de la Rúa, the Alianza candidate, defeated the Peronist candidate Eduardo Duhalde in the primaries. At that time he was mayor of Buenos Aires. In the simultaneous elections held for half of the seats in the House of Representatives, the Alianza obtained 63 seats and the PJ 50. The coalition of De la Rúa obtained 127 of the 257 seats in the House of Representatives as a result of this election result, while the Peronists went back to 101 seats.

Period De la Rúa

On December 10, 1999, De la Rúa was sworn in as president, and he pledged to tackle corruption and give more attention to social policy. The problem, however, was that the new governing coalition did not have a majority in parliament.

Due to the ongoing economic malaise and ongoing street protests, De la Rúa was forced to resign on December 20, 2001. A very restless Christmas period followed with three interim presidents, successively Ramón Puerta, Adolfo Rodriguez Saá and Eduardo Caamaño. Parliament intervened and appointed Peronist Eduardo Duhalde to complete De la Rúa's term of office until the elections of March 30, 2003.

Period Kirchner

The presidential elections of that day were won by former president Carlos Menem, but with too few votes to immediately become president again. In the following polls, Menem fell far behind his competitor Nestor Kirchner. Menem then decided to withdraw, after which Kirchner became the new president of Argentina on May 25, 2003.

President Kirchner's popularity is high, not least due to the unexpectedly favorable economic recovery that occurred during his presidency. President Kirchner cashed in on his popularity in parliamentary seats in the October 2005 congressional elections, but clashed severely with his previous patron Duhalde when he took over from Duhalde's Peronist party apparatus in Buenos Aires Province (40% of voters) .

The political cards are being shuffled in view of the upcoming elections in October. This again shows that politics is more focused on the personality of a leader than on a party. Attempts to support or stop the current president Kirchner lead to all kinds of alliances that cause parties to split up and merge. For example, part of the “radical” party, the UCR, supports President Kirchner (Peronist) they are called the “K” Radicals. Also within the same party are the “L” Radicals of former economy minister Lavagna who was fired by President Kirchner in 2006 and is now one of the main rivals in the upcoming presidential election. There is another split-off within the “radical” party, the “R” Radicals, who support neither President Kirchner nor Lavagna. This split-off is headed by the general secretary of the UCR, Margarita Stolbizer. The “R” Radicals are now trying to form an alliance with the center-left Alternativa para una República Igualitaria (ARI), a party that split in 2001 from the UCR.

The divisions within UCR and also within the other opposition parties ensure that President Kirchner is the favorite in the run-up to the elections. President Kirchner, however, still has doubts about whether he will actually run for election. It is also possible that his wife, Senator Cristina Fernández, also popular, will join him instead.

Period Fernandéz

Argentina Cristina FernandézPhoto: Presidencia de la N. Argentina CC 2.0 no changes made

Argentina Cristina FernandézPhoto: Presidencia de la N. Argentina CC 2.0 no changes made

In October 2007, Cristina Fernández won the elections and in December 2007 she was appointed president of Argentina. In July 2009, President Fernandez's Peronist party loses the absolute majority in parliament. At the end of 2009 and in February 2010, the row between Great Britain and Argentina continues over the control of sea areas, partly as a result of a British plan to drill for oil. In 2011, Cristina Fernández wins the elections again, due to strong economic growth. In July 2012, Videla was sentenced to 50 years in prison. In 2013, Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Buenos Aires is elected Pope of the Roman Catholic Church. He is the first South American to hold this position. In November 2013, President Fernández made changes to her government squad. 2014 was dominated by the debt crisis, Congress decided to restructure in September.

Period Macri

In November 2015, Mauricio Macri, the conservative mayor of Buenos Aires, wins the presidential election of Peronist Daniel Scioli. He will take office as the new president in December. In February 2016 Argentina enters into a debt payment agreement to a US hedge fund, thus regaining access to the international credit market. In October 2017, the coalition around Macri wins the parliamentary elections, which is seen as a test of his reform policy. In November 2017, the court sentenced 48 defendants for their role in torture and disappearances during the Videla regime. At the same trial, Julio Poch, the Argentinian / Dutch pilot who was held in custody for 8 years for alleged involvement in death flights, is acquitted. In May 2018, the government is raising interest rates in an effort to stop the fall of the Peso. Alberto Ángel Fernández, president of ArgentiniaPhoto: Argentina Presidency of the Nation CC 2.5 Argentina no changes made

Alberto Ángel Fernández, president of ArgentiniaPhoto: Argentina Presidency of the Nation CC 2.5 Argentina no changes made

Period Fernández

In August 2019, Macri unexpectedly loses the preliminary round of the presidential election to center-left candidate Alberto Ángel Fernández, who also wins the presidential election later in October of that year and is the new president since 10-12-2019.

Sources

Argentinië

Van Reemst

Doef, P. van der / Argentinië

Elmar

Encarta Encyclopedie

Holtwijk, I. / Argentinië : het land van Máxima

Bert Bakker

Thielen, J. / Argentinië : mensen, politiek, economie, cultuur, milieu

Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen ; Novib

CIA - World Factbook

BBC - Country Profiles

Last updated January 2026Copyright: Team The World of Info