MADAGASCAR

History

History

History

First inhabitants

Although Madagascar is relatively close to the African mainland, it remained uninhabited until some 1,500-2,000 years ago. The first inhabitants did not come from Africa, but from Malaysia and Indonesia, 6400 km away. The vast majority of the population is descended from these people. It is suspected that these people eventually ended up in Madagascar via East Africa. They also brought their own food, which is why rice is still the main food for the Madagascan today. After a turbulent history, the population has been divided into 18 tribes, the main tribe being the Merina. Monument in Antsirabe, Madagascar, with the head of a zebu, the names of the 19 tribes that make up the Malagasy populationPhoto: Aviad2001 CC 4.0 International no changes made

Monument in Antsirabe, Madagascar, with the head of a zebu, the names of the 19 tribes that make up the Malagasy populationPhoto: Aviad2001 CC 4.0 International no changes made

The first Europeans arrived under the Portuguese flag in Madagascar in the year 1500. The existence of Madagascar was recorded by Marco Polo and by Arab cartographers long before these Europeans arrived. In the centuries that followed, the Portuguese, Dutch and English often tried in vain to settle permanently on the island. Pirates who had their base in Madagascar from the end of the 17th century were successful.

Sixteenth to eighteenth century

Three little kingdoms gradually emerged in Madagascar: Menabe in the west, Zana-Malata in the east and Merina on the central plateau. At the end of the 16th century, the Menabe conquered large tracts of land north along the coast. The eastern highlands were also occupied under King Andriamisara I. His successor Andriandahifotsy wanted to put the entire south and east of Madagascar under his rule, but this was not entirely successful. Later, during the reign of Andriamandisoarivo (1685-1712), his disinherited son founded the kingdom of Boina which lasted until the early 19th century. At the beginning of the 18th century, Ile Sainte Marie became the headquarters of the pirates.

Ratsimilaho, son of an English pirate and Madagascan princess, managed to merge the Zana-Malata and some rival tribes into the realm of Betsimisaraka. In 1750, Ratsimilaho's daughter Bety married a French corporal, Jean-Onésime Filet. As a wedding gift they received the island of Ile Sainte Marie. After the death of Ratsimilaho, Bety ceded the island to the French. Her son Zanahary took over the kingdom from her, but it soon fell apart under his rule. At the end of the 18th century, a Hungarian-French slave trader, Maurice-Auguste Comte de Beniowski, settled in Antongila and proclaimed himself Emperor of all Madagascar. Count Maurice de Benyovszky, MadagascarPhoto: User: Qpeezee CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Count Maurice de Benyovszky, MadagascarPhoto: User: Qpeezee CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In 1786 he was deposed by French troops. In 1787 Chief Ramboasalama ruled the Merina tribe and succeeded in bringing all members of the tribe into line. He called himself Andrianampoinimerina (full name: Andrianampoinimerinandriantsimitoviaminandriampanjaka = The Hope of Imerina) and thus the Merina became the leading tribe of Madagascar who at that time controlled half the island.

Nineteenth and twentieth century

His son Laidama succeeded his father after his death in 1810 and called himself Radama I. With the help of a 35,000 strong army, he gradually conquered and occupied all of Madagascar. He got the kingdom of Menabe by marrying the daughter of the king. In doing so, he fulfilled his vow that “my kingdom shall have no bounds except the sea”. He directly established relations with the European powers. For example, a French sergeant was appointed commander of his army, and an Englishman became his personal adviser. In 1820, a treaty was concluded with the English who from that time regarded Madagascar as an independent state under Merina rule. From that time on, the first missionaries also came to Madagascar to convert the population to Christianity. The first schools were also built and the Madagascan language was written down. The first Bible in Madagascan was printed in 1835. Tomb of Radama I at the Rova of Antananarivo in MadagascarPhoto: Lemurbaby CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Tomb of Radama I at the Rova of Antananarivo in MadagascarPhoto: Lemurbaby CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Radama died in 1828 and was succeeded by the xenophobia Ranavalona I who immediately declared Christianity illegal. Many missionaries fled or were killed. In 1861, Ranavalona died and was succeeded by her son, Radama II. He was much more progressive than his mother. This gave the population freedom of religion, modernized the legal system and opened Madagascar again to foreigners. When the Europeans were allowed to re-enter, Christianity soon became more or less the official religion.

In 1862, the capital Antananarivo was hit by a mysterious contagious disease. Deep disagreements arose between the elite of the Merina tribe, and all this resulted in the death of Radama II, murdered by the Prime Minister's brother. He was succeeded by his wife, who from then on called herself Rasoherina. She married, according to tradition, the Prime Minister. However, her power was limited by an agreement that stipulated that she could only make decisions with the consent of the ministers. Then the Prime Minister's brother, Rainilaiarivony, comes back into the picture. He organizes an uprising against his brother, occupies his ministry and marries his wife Rasoherina! Rasoherina therefore remained on her throne until 1868.

She was succeeded by Ranavalona II, who married Rainilaiarivony again. Ranavalona II died in 1883 and was succeeded by Ranavalona III. Meanwhile, due to the construction of the Suez Canal in 1869, the English were no longer as interested in Madagascar as a political and strategic foothold in the Indian Ocean. In 1890 France and Great Britain signed a treaty in which Madagascar came under the influence of France and Zanzibar under that of Great Britain. In 1894, the French demanded that Queen Ranavalona III abdicate. Statue of Ranavalona III, MadagascarPhoto: Heinonlein CC 4.0 International no changes made

Statue of Ranavalona III, MadagascarPhoto: Heinonlein CC 4.0 International no changes made

She refused and France sent an army to Madagascar. Despite great losses from disease, the French captured Antananarivo on September 30, 1895. He tried to eliminate the Merina aristocracy by banning the Madagascan language, among other things. All British influences were also suppressed. French became the official language and in 1897 the French managed to depose Ranavalona and she was exiled to Algeria. The French immediately tried to further develop the country by investing in the economy, transport, construction and education. These developments soon created a French-oriented Madagascan elite. Most Madagassians didn't like it, and nationalist groups quickly emerged among the Merina and Betsileo tribe. They organized many strikes and demonstrations.

During World War II, Madagascar was under the pro-German Vichy regime of Marshal Pétain. The British soon conquered Madagascar because they feared that the Japanese would use the island as a base. Madagascar, however, was returned to the "Free French" of General Charles de Gaulle in 1943. After the war, national feelings flared up again, ultimately resulting in an uprising in 1947 that was bloody down by the French (80,000 dead is estimated). Political parties were first formed in the 1950s. The most important party was Philibert Tsiranana's Parti Social Démocratie (PSD). In 1958, the Madagassians voted in a referendum in favor of autonomous republic status as part of the French overseas territories. President Tsiranana meets the West-German chancellor Willy BrandtPhoto: Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-F013783-0033 / Wegmann, Ludwig / CC-BY-SA 3.0 no changes made

President Tsiranana meets the West-German chancellor Willy BrandtPhoto: Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-F013783-0033 / Wegmann, Ludwig / CC-BY-SA 3.0 no changes made

Independence

Not long afterwards, the declaration of independence followed in 1960 and Tsiranana became the first president. He allowed the French to retain control of trade and banking. France could also hold military bases. In fact, this meant that the French still ruled Madagascar. The Merina tribe increasingly resisted continued French "domination" and sought more and more support from the Soviet Union and communism. Tsiranana was strongly against this and focused more on South Africa. Tsiranana's popularity declined rapidly, however, as the economy deteriorated in Madagascar in the 1960s.

In September 1972, after massive demonstrations, Tsiranana resigned and handed over power to the Army Chief of Staff, General Gabriel Ramanantsoa. Ramanantsoa immediately introduced fundamental changes. French military bases were closed, agricultural collectivization began, and diplomatic relations with South Africa, Israel and Taiwan were frozen. Relations with China and the Soviet Union strengthened. The departure of the French soon made it clear that Madagascar was very dependent on their development money and technical aid. Soon heated discussions followed about the path they had taken. Bust of President Richard Ratsimandrava in the high school amphitheater, MadagascarPhoto: LycéeGallieniAndohalo CC 4.0 International no changes made

Bust of President Richard Ratsimandrava in the high school amphitheater, MadagascarPhoto: LycéeGallieniAndohalo CC 4.0 International no changes made

In February 1975, after several coup attempts, General Ramanantsoa was forced to resign and replaced by Colonel Richard Ratsimandrava. However, this was shot after just one week and power was taken over by a number of officers from the army. These officers were soon called back by a number of officers loyal to the murdered Ratsimandrava. A new government was appointed under the leadership of Didier Ratsiraka, previously minister of foreign affairs. Due to these developments, exports had stagnated, all schools were closed and there were hardly any other economic activities. Ratsiraka tried to get things going again with radical political and social reforms. He mainly focused on communist countries. Economically he was a bit more pragmatic. All banks were nationalized and a number of public organizations were set up to deal with different sectors of the economy. Didier Ratsiraka, former president of MadagascarPhoto: Cerveau KOTOSON CC 4.0 International no changes made

Didier Ratsiraka, former president of MadagascarPhoto: Cerveau KOTOSON CC 4.0 International no changes made

In 1981-1982 another serious economic crisis followed, forcing Ratsiraka to loosen the reins a little. As a result, he also received more money from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. As a result of this foreign aid, the economy recovered somewhat, albeit temporarily. In March 1989 Ratsiraka was re-elected for another seven years after dubious elections. Riots killed six and injured dozens. Months of demonstrations and strikes against the Ratsiraka regime followed in 1991, causing the already fragile economy to cease functioning. New riots followed and 30 people were killed. France exerted heavy pressure and demanded new elections.

In October 1991, Ratsiraka signed an agreement with the opposition calling for new elections. These elections were won by the doctor Albert Zafy, who was trying to make Madagascar a democracy. In this way, parliament was given far-reaching powers, including the removal of the president with a two-thirds majority. Despite all the good intentions, this experiment also ended in complete chaos. Within three years, eight cabinets fell and a new prime minister was elected three times. The economy also collapsed and the population became poorer. After those three years, Zafy demanded his power back. Albert Zafy (left), former president of MadagascarPhoto: Yvannoé CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Albert Zafy (left), former president of MadagascarPhoto: Yvannoé CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Parliament immediately tried to impeach him, but he refused. He did, however, call new elections that were won by the former president, Ratsiraka. Ratsiraka was now trying to make Madagascar a federal state like the United States. Madagascar is already divided into autonomous self-governing provinces. There is also a strong focus on economic growth and the reconstruction of education and health care. The French are also welcome investors again. Ratsiraka quickly organized a referendum asking the people to return power to the president. The people voted in favor by a large majority, tired of the unstable political conditions of the past decades. The 1998 elections were again won by Ratsiraka's party. Pascal Rakotomavo became prime minister. After the 1999 municipal elections, pragmatic, often non-party businessmen came to power in almost all major cities.

21th century

Presidential elections were held on December 16, 2001, with former president Ratsiraka and Marc Ravalomanana, the mayor of the capital Antananarivo as the main candidates. Soon after the elections, strong rumors of irregularities circulated. With massive popular support, the mayor of Antananarivo proclaimed himself head of state and appointed his own "government". He claimed victory because he would have received 52% of the vote, while no candidate would have more than 50% of the vote, according to the election commission, which meant a second round was needed. The official result put Ravalomanana in front of the incumbent president, Didier Ratsiraka with 46% against 41% of the vote. Marc Ravalomanana, former president of MadagascarPhoto: Mogens Engelund CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Marc Ravalomanana, former president of MadagascarPhoto: Mogens Engelund CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

This was followed by a period of peaceful protests in the capital by mass demonstrations and strikes, on a scale unprecedented. The crisis marks a major change in the country's political relations, where Ratsiraka's Arema party appeared to be heading for an easy victory. Ravalomanana is backed by the united opposition, which is located in different parts of the country and includes diverse social and ethnic groups. Even after the elections, the opposition has managed to maintain its unity. Arema, however, does not have a majority in the country, but has so far maintained its position due to the fragmentation of the opposition and the willingness of some opposition leaders to hold positions in government or to support government policies such as economic reforms. Ratsiraka has not been able to properly assess support for the opposition. He declared martial law, a tactic that failed as the security forces proved unwilling to take sides in the conflict. In the eyes of the military, the army is at the service of the state and not individual politicians.

In response to Ravalomanana's takeover in the capital, Ratsiraka granted new powers to the governors of the six provinces. They also belong to the Arema party. One of the provincial governors distanced themselves, but the other five sided with Ratsiraka, who installed an alternative government in the port city of Toamasina (aka Tamatave). However, this situation was not further substantiated by Ratsiraka himself. Emblem of the Democratic Republic of MadagascarPhoto: Thommy CC 1.0 no changes made

Emblem of the Democratic Republic of MadagascarPhoto: Thommy CC 1.0 no changes made

Several African mediation attempts followed to find a solution to the crisis. The main aim of the mediation efforts in the conflict by representatives of the AU (African Union) has been to prevent the division of Madagascar's national unity. Ultimately, this mediation attempt resulted in a recount of the votes. Ravalomanana received more than 50% of the vote and was proclaimed president in May 2002. New presidential elections are scheduled for April 2007. At the end of 2007, parliament will also be elected. In September 2007, President Ravalomanana's party won 106 out of 127 parliamentary seats.

At the end of January 2009, dozens of people were killed in violent protests. The riots started in the capital Antananarivo, but soon spread. The protesters demanded the resignation of President Ravalomanana. It angered the opposition by shutting down a TV station of its political rival Andry Rajoelina, the mayor of Antananarivo. Protests in the capital of Madagascar, Antananarivo (2009)Photo: Fanalana_azy CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Protests in the capital of Madagascar, Antananarivo (2009)Photo: Fanalana_azy CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

In March 2009, Ravalomanana resigns and hands over power to the military. In April 2009, new president Andry Rajoelina issues an arrest warrant against his rival Ravalomanana, announcing his return to Madagascar. In June 2009, Ravalomanana was sentenced in absentia to 4 years in prison. In February 2010 Rajoelina announces elections in May. This is repeatedly delayed. In June 2010, the EU decided to suspend development aid due to insufficient progress in the democratic process.

From 2011 to 2013 there are always elections to be held. Ultimately, those elections will be held and in January 2014 Hery Rajaonarimampianina will become the new president. In 2015, the parliament wants to initiate an impeachment procedure against the president, the constitutional court disapproves. The senate will be elected in December 2015, after it was dissolved six years ago. Hery Rajaonarimampianina, former president of MadagascarPhoto: Chatham House.CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Hery Rajaonarimampianina, former president of MadagascarPhoto: Chatham House.CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

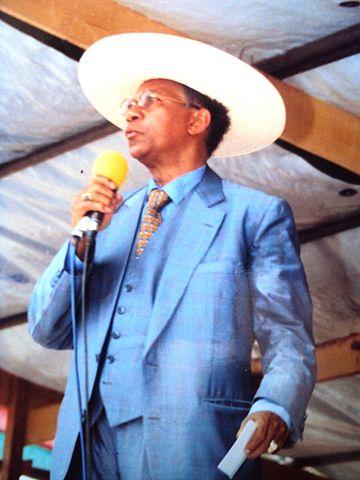

In January 2019 Andry Rajoelina wins presidential election, defeating President Rajaonarimampianina and his long-standing rival Marc Ravalomanana. President Rajoelina meets United Nations secretary-general Ban Ki-MoonPhoto: Jeannot Ramambazafy CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

President Rajoelina meets United Nations secretary-general Ban Ki-MoonPhoto: Jeannot Ramambazafy CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Sources

Bradt, H. / Madagascar

Bradt

Greenway, P. / Madagascar & Comoros

Lonely Planet

Lanting, F. / Madagascar : een wereld verdwaald in de tijd

Fragment

Rozeboom, A. / Madagaskar: mensen, politiek, economie, cultuur, milieu

Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen/Novib

Stevens, R. / Madagascar

Chelsea House Publishers

CIA - World Factbook

BBC - Country Profiles

Last updated February 2026Copyright: Team The World of Info