CAMPANIA

History

History

Popular destinations ITALY

| Campania | Lombardy | Sardinia |

| Sicily | Tuscany | Umbria |

| Veneto |

History

The History of Campania is broadly similar to that of the history of Italy described below.

Prehistory and Antiquity, Ligurians and Etruscans

Italy Graves EtruscansPhoto: NormanEinstein CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Italy Graves EtruscansPhoto: NormanEinstein CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

The spread of human habitations across Italy began earlier than in northern Europe. Since 2000 BC. several peoples settled on Italian territory. Around 1200 BC. the Ligurians and Italians entered Italy from the north. The Ligurians were Bronze Age settlers from southern France, and settled in central Italy, near today's Rome. The Italians came from the Danube region in Central Europe.

People from the Eastern Mediterranean explored the coast of Italy from about 5000 BC. The Phoenicians, at that time, founded Carthage in North Africa and trading posts in Italy. In the 8th century BC. the Greeks founded colonies in Sicily and southern Italy. These colonies, along with Syracuse, Agrigento, Crotone and Taranto, were called Magna Graecia (Greater Greece). In addition to trading activities, many philosophers, scientists and writers also moved to the Greek colonies in Italy. Large temples and open-air theaters were also built, including theaters in Agrigento and Paestum (near Naples).

While the Greeks colonized southern Italy and Sicily, Etruscans founded cities in Central Italy.

The Etruscans are still more or less a mystery and no one is sure where exactly they came from. Initially the Etruscans occupied the areas around the rivers Arno and Tiber and the mountains of the Apennines, later they moved to the Po Valley and towards Rome. A federation of twelve city-states, including Volterra, Fiesole, Arezzo, Perugia and Chiusi, emerged in Central Italy in the region we now know as Etruria.

The Etruscans became rich through the iron, copper, and silver mines and trade in the eastern Mediterranean. Their cities were perched and surrounded by fortifications. They also built bridges, streets and canals.

Rome and the Romans

The genesis of Rome is unclear. As the city became powerful, legends arose about the foundation and origin of the city and its empire. The "official" version became that Aeneas, son of Aphrodite, came from Troy to Latium. His son Ascanius founded Alba Longa. Finally, Romulus and Remus, twin sons of Mars and Rhea Silvia, daughter of the king of Alba Longa, founded the city of Rome. The founding year was 752 BC.

King's Age and Republic

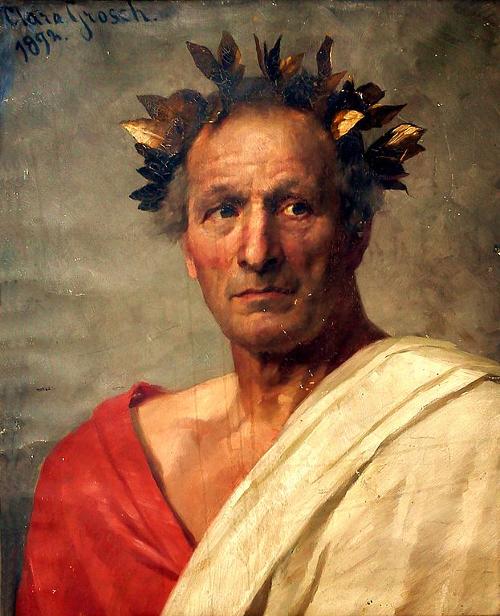

Italy Julius CaesarPhoto: Clara Grosch in the public domain

Italy Julius CaesarPhoto: Clara Grosch in the public domain

The official history of Rome starts with the merger of the Palatinus and the Quirinalis, the two oldest inhabited hills. However, this city soon came under Etruscan rule, so there was no Roman empire yet. After the exiled king Tarquinius Superbus in 496 BC. was finally defeated and the Romans and Latins made an alliance, which is considered, to some extent, as the beginning of the Roman Empire. There was also a struggle with the Volsci, the Sabines and the Aequi. An established fact of this period is the conquest of Veji by Camillus; this battle lasted from 405 BC. to 396 BC.

The invading Gauls halted the advance of the Romans in 387 BC. The neighboring peoples like the Etruscans and the Volsci also revolted against Roman rule. In 358 BC. the Latini and the Hernici capitulated while a treaty was concluded with the Etruscans. In the Second Samnite War, the Romans suffered a major defeat at Caudium in 321 BC. Yet they saw an opportunity to take over the power in Central and Southern Italy for good.

In the Third Samnite War (298-290 BC), rebellious Etruscans, Gauls and Umbrians were finally defeated at Sentinum. Due to the expansion of power in Campania and Samnium, Rome came into conflict with Taranto. The city of Taranto, even with the help of the Greek king Pyrrhus of Epirus could not prevent a defeat in 275 BC. at Beneventum.

Ultimately, peace reigned throughout Italy. The authority of the Romans was maintained by a sophisticated system of colonies and the roads that ran through them. Some cities were granted city rights and had a high degree of self-government. The only obligation they had was to provide soldiers for the Roman army.

Due to the conquests in southern Italy, the Romans met strong resistance from the Sicilians and the Carthaginians in North Africa. Three Punic Wars against Carthage took place in the period 264-146 BC. In the First Punic War (264-241 BC), Sicily became the first Roman province and Sardinia and Corsica were annexed. After the Second Punic War, Spain became a Roman territory and the Carthaginians' allies, the Macedonians, were defeated. Syria was also finnaly defeated by the Romans in 190 BC. and forced to make peace that severely curtailed its power. In the Third Punic War, Carthage was destroyed in 146 BC. and became a Roman province. In 168 BC. Perseus of Macedonia was defeated and his empire and Greece in 146 BC. were incorporated as a province. The great trade competitor Corinth was also devastated in 146 BC., and western Asia Minor was destroyed in 133 BC. and added to the expanding empire.

All these conquests created a completely different social structure in the Roman Empire. Tax leaseholders in the provinces became richer and more powerful, causing the peasant population to suffer greatly. The Senate, the most powerful body in the empire, soon lost control and the ruling class became deeply divided. This situation would eventually lead to a number of civil wars in the 90-30 BC period, and always the cause were disputes between generals, politicians and other interest groups.

The First Civil War (88-81 BC) was about supreme command of the army between Marius and Sulla. Marius was first expelled by Sulla but later Marius's supporters returned to power. In 82 BC. the supporters of the now dead Marius were defeated by Sulla, who restored the power of the Senate and put an end to the dictatorship.

After Sulla's death in 79 BC. a battle arose over his succession. No one was able to seize power alone, and therefore the so-called "First Trinity" with Crassus, Pompey and Julius Caesar was created. Crassus was soon killed in 53 BC. and Caesar left in 58 BC. to northern Gaul, which he managed to subdue in eight years, and in this way also he managed to gain the confidence of the army. Pompey turned more and more towards the senate and in 52 BC. he had acquired so much power that he could almost be called dictator. A conflict between Caesar and Pompey was unavoidable and in the Second Civil War (49-45 BC) Pompey was defeated and killed.

Caear was now the sole ruler and began the reconstruction of the Roman state, laying the foundation for the future empire. In 44 BC. he was assassinated by republican senators. A confused time followed, culminating in the founding of the Second Trinity in 43 BC, which consisted of Octavian, Lepidus and Mark Antony. These "three men" divided the empire but Lepidus was soon put aside.

Anthony ruled the east and Octavian got the west. However, Anthony fell under the influence of the beautiful Egyptian Cleopatra and a Third Civil War in 31 BC. was the result. Antony and Cleopatra were defeated at Actium, and Egypt became a special domain of Octavian within the Roman Empire. This victory assured Rome a political supremacy in both the western and eastern Roman Empire.

Principate (31 BC - 284 AD)

Italy AugustPhoto: Till Niermann CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Italy AugustPhoto: Till Niermann CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

The Republic came to an end with Octavian, who called himself "princeps", which means the first, and the period that followed is called the "Principate" because his successors also were called "princeps". In 27 BC. Octavian deposited his proxies, but had them restored by the Senate, and then received the honorary title of Augustus. Under his leadership, the empire achieved order and prosperity and managed to consolidate natural borders.

Augustus was succeeded by his adopted stepson Tiberius who ruled from 14 to 37 AD. and faced somewhat over-zealous senators accused of high treason. Under his extravagant successor Caligula, disorder reigned in the empire that was restored under Claudius II (41-54). After this it went wrong again. Agrippina, the wife of Claudius, had him poisoned in order to put her son Nero on the throne who would rule from 54 to 68. At that time it was going well in Rome, but under Nero it was largely lost again due to his excessive behavior. He had, among other things, his own mother murdered and is said to have been responsible for the great fire of Rome. Then a revolt broke out and he was killed by a slave, bringing the Julian-Claudian dynasty to an end.

Nero's reign was followed by a Year of the Three Emperors with Galba, Otho and Vitellius. Vitellius was overthrown by Vespasian, the commander of the eastern legions. Under his rule, revolts arose in both the east and the west, also among the Jews in Jerusalem, crushed by Titus, and in the west by the Batavians, crushed by Civilis. Titus, the son of Vespasian, only reigned for a few years, dealing with the volcanic disaster that hit Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79. Titus was succeeded again by Domitian who reigned until 96. After Domitian's murder, no male successor was available and the senate chose Nerva as emperor. With him began a whole series of emperors who were supposedly chosen by adoption. Trajan was the first emperor not even born in Italy. It was he who went on the conquest again and conquered Dacia, later Romania, among others. Mesopotamia was also temporarily occupied by the Romans.

The Roman Empire was now at the height of its power but it soon became apparent that it was no longer controllable due to its size. Hadrian, for example, stopped his conquests in the east and was forced to fortify himself along all borders, including construction of the "Hadrian's Wall" in Great Britain. After Hadrian, two more emperors with the name Antonius followed and the line of emperors-by-adoption was closed. The reign of Antoninus Pius lasted until 161 and was characterized by calm throughout the empire.

Under his successor Marcus Aurelius, many problems arose, both at home and abroad, and the empire was ravaged by epidemics. His son Commodus and his successor Pertinax were even murdered. After some problems with the succession, Septimius Severus, an African, was able to get the rule in 193. He became known for limiting the influence of the senate and conquering a new province: Northern Mesopotamia.

Caracalla (211-217) and his successor Macrinus (217-218) were murdered. Alexander Severus reigned until 235 and was the last of the Severo-Syrian dynasty. Around this time, the senate regained its influence. But campaigns against the Sassanids in the east and Germans in the west did not end well, and Severus was eventually killed by a rebellious general. Under one of his successors, Decius (249-251), Christianity was fiercely contested, but the empire had long been threatened by other things, including the financially poor condition, the Germans who united and became increasingly dangerous. The differences between rich and poor also caused many internal tensions.

After 250 the chaos was complete. The Goths continued to advance and large parts of the immense empire were occupied and plundered by all kinds of peoples without much opposition from the Romans. Under Gallienus (253-268) there was some recovery and under his successor, the Goths who had already penetrated into Serbia, were defeated. A partial reconstruction of the empire followed under Aurelian. After the murder of Aurelian, another time of fighting emperors followed, which ended with Diocletian who was proclaimed emperor by his soldiers.

Dominate (284–476)

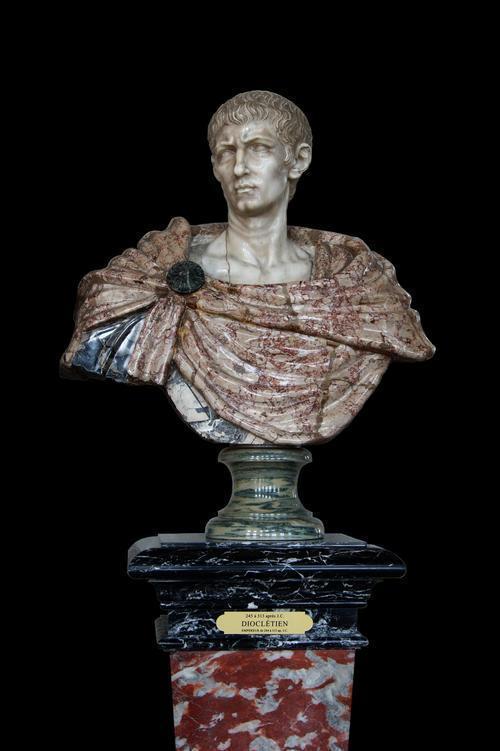

Italy DiocletianusPhoto: Jebulon in the public domain

Italy DiocletianusPhoto: Jebulon in the public domain

Diocletian was an absolute ruler/autocrat who deufued himself during his life and his title spoke for itself: "dominus et deus" (lord and god). On the other hand, he divided supreme authority among two Augusti (including himself), each of whom had two Caesares under him; one therefore speaks of the "tetrarchy". The special position of Italy as a whole came to an end and the empire was divided as follows: the east with Nicomedia as its capital under Diocletian; Italy and Africa with the capital Milan under Maximianus; Gaul, Spain and Britain with Trier as capital under Constantius Chlorus; and Illyricum and Greece with Sirmium as capital under Galerius.

The Roman Senate was only a municipal council for Rome, which no longer even remained the capital of an empire and had to cede this function to Milan. The senators, however, remained a formidable economic factor because they were, together with the emperor, the largest landowners. By bureaucratising and militarizing the administration, the Romans managed to keep the Persians at a distance and could maintain unity within the empire. In 305, Diocletian and Maximian resigned and civil wars promptly broke out with at one point six Augusti vying for supremacy.

This was accompanied by the necessary massacres and it was not until Constantine the Great that a period (324-337) of one-man government began again. Under Constantine, Christians were again favored, and after the Edict of Milan in 313, religious freedom reigned in the Roman Empire. This was also done out of self-interest to gain support from both pagan and Christian sides for the policy of imperial unity, and the capital thus became Constantinople, at the intersection of cultures and routes to all parts of the empire.

The family struggle for supremacy after Constantine's death was won by Constantius II, who ruled from 353 to 361. Constantius was succeeded again by Julian, who had been proclaimed emperor by the army as the only surviving relative of Constantine. Julianus Apostata, the "Apostate" is said to be the last non-Christian emperor (361-363). His Christian successors Jovian and Valentian (364-375) were confronted with strongly divided Christians and danger from outside due to the great Germanic migration. Several family members had been appointed co-regents for the East, which inevitably led to a time of unrest and civil war.

This time of turmoil was brought to an end by Emperor Theodosius I who divided the empire among his two sons in 395. However, what was meant to be an administrative separation turned out in practice to result in a separation in two separate states. Arcadius got the east that was under regency from Rufinus. Honorius got the west under regency of Stilicho.

The impending doom of the Roman Empire was getting closer and closer. The western part of the empire fell apart after many wars in the 5th century. The Visigoths threatened to invade, after which the legions from the west were called back. This had a counterproductive effect because it allowed Germanic peoples to advance further and further.

After the murder of Stilicho, the Goths invaded Italy and even Rome was sacked in 410. In 415 the Visigoth Empire was founded in southern France, Spain and Africa, which was important to the Romans because it served as a granary. The empire was further weakened by the mutual jealousy of the generals. There was therefore no question of joint action against the advancing Huns led by Atilla de Hun. General Aëtius managed to stop Attila in 451, but a year later the Huns invaded Italy but were unable to get through to Rome. Aëtius was killed by the emperor and the emperor himself was murdered by a Germanic soldier, bringing the last imperial dynasty, the Theodosian, to an end.

In 455 the Vandals landed in Italy and took Rome in a very bloody way. Until about 476 emperors were appointed by the commander of the Germanic troops, Ricimer, and equally easily deposed. After the death of Ricimer, the German Orestes appointed his son as emperor. This Romulus was deposed by the Germanic Odoaker who in 476 called himself "king of the Germans in Italy". This marked the definitive end of the emperorship and the Roman Empire in the western part of the empire. The Eastern Roman Byzantine Empire flourished again and did not collapse until 1453 after the fall of Constantinople.

Middle Ages

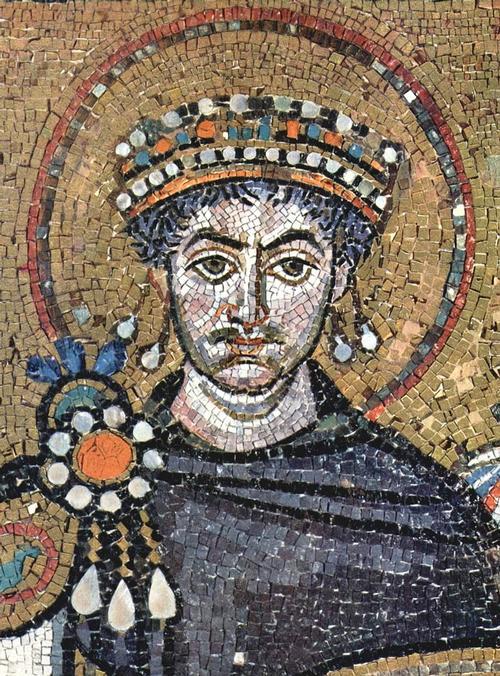

Italy Justinianus IPhoto: Public domain

Italy Justinianus IPhoto: Public domain

In 493 the (then) capital Ravenna was conquered by the king of the Ostrogoths, Theodoric the Great. He thereby also gained control of all of Italy, but his successors had no chance against the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, who occupied Italy in 535. In 568, northern and central Italy was conquered by the Lombards while the rest of Italy remained under Byzantine rule and Rome was entrusted to the authority of the bishop, i.e., the Pope.

The Longobards founded the kingdom of Pavia and the dependent duchies of Spoleto and Benevento. The regions under Byzantium were ruled by "duces", regional governors of the emperor.

Already at the end of the 5th century, Pope Gelasius I had claimed the primacy of the ecclesiastical over the secular authority; his successors, notably Gregory the Great, emphasized this even more strongly, which prevented Byzantium's military support against the Lombards. In the 8th century the popes sought support elsewhere against the threatening Lombards, and ended up with the Franks. These people first came to Italy around the mid-8th century and their rule quickly expanded. They placed the papacy under their protectorate and laid the foundations for the Papal State.

Charlemagne established himself as king of the Lombards (774) and was crowned emperor by Pope Leo III on Christmas night in Rome 800 AD, thus definitively linking the emperorship of the west to the papacy. This imperial support would last about two centuries and was desperately needed to fend off all kinds of opponents and enemies. In 887, Charles the Fat lost control of Italy and large areas of southern Italy were lost to the Saracens. In Northern Italy, a number of rulers fought for hegemony.

In 962, the German king Otto the Great was crowned emperor of the Holy Roman-German Empire, raising the papacy to greater prestige. However, he made it subordinate to politics, but laid the foundation for the later power of the church. In the meantime, the history of southern Italy developed according to its own pattern. Dukes, mostly representatives of the Byzantine bishops and Saracens, ruled, and at the beginning of the 11th a number of city republics (including Gaeta, Naples and Amalfi) became very powerful. In 1016 the Normans infiltrated Italy after being used in the fight against the Saracens. In 1071, the Norman Robert Guiscard conquered Bari, ending Byzantine power in Italy. By the year 1200, almost all of the southern Italy was Norman territory and Sicily was also conquered from the Saracens.

In the Investiture Controversy (the conflict between Pope and Emperor over the Church in the Roman Empire that lasted from 1075 to 1122), the whole of Italy had taken sides. After the Concordat of Worms (1122), the struggle was shifted from ideological to purely political territory: fellow players were the Pope, the Emperor and the Normans in the south.

All this led to the increasing power of the northern and central Italian cities. However, the Hohenstaufen retained Sicily as an important point of support because Emperor Henry VI married the heiress of Sicily, Constantia d'Altavilla. Sicily therefore remained a threat to the papacy. Imperial authority in Italy disappeared with Emperor Frederick II making a failed attempt to evade papal authority. In the course of the 13th century, more and more city-states emerged in the north of Italy, where military personnel held power. In 1268, the Pope awarded the Sicilian Empire to Charles of Anjou, who then became King of Naples and Sicily. This could happen after the death of Frederick II's successor, Manfred. It was soon clear that Charles wanted to have dominion over all of Italy, but the Pope managed to break his power. And after the Sicilian Vespers (= the uprising that broke out in Palermo in Sicily on March 31, 1282 and from there spread all over the country) he even lost Sicily that was assigned to the Spanish Aragón. After the "Babylonian" captivity, the worldly power of the Pope came to an end.

In the 15th century, the struggle for power took place between Florence, Venice and Milan. German and French rulers, as well as smaller city republics in Italy themselves, took sides. In the south, Aragón decided the battle against Anjou and southern Italy as the kingdom of Naples fell to Alfons V of Aragón, who was already king of Sicily at that time. Around 1450, what appeared to be an Italian equilibrium between north and south emerged, but various mutual wars showed a very shaky balance.

In the cultural field, Italy took a tremendous lead in the Renaissance and had a profound influence on the rest of Europe.

From the End of the Middle Ages to Unification

Italy Catherine de MediciPhoto: Public domain

Italy Catherine de MediciPhoto: Public domain

At the end of the 15th century, a decline begun and Italy became a toy of the great European powers, with the battle between Habsburg and Valois mainly fought in Italy. In 1494 Charles VIII of France entered Italy because he believed he could claim Naples. After all, he was the heir to the House of Anjou. Aan unholy alliance with the Pope, the Emperor, Milan and Venice, among others, meant that Charles had to withdraw from Italy as early as 1495. Charles's successor, Louis XII, embarked on the same adventure and claimed Milan in addition to Naples.

This city was occupied in 1499 and Naples was conquered with the help of Ferdinand II of Aragón. In 1505, however, the French withdrew from this coalition, making the entire kingdom of Spanish Aragón. The French tried again, and now Venice was besieged in 1508. Again, they were forced to withdraw because allies turned against the French king (1513). In 1556 Milan came to Spain as a feef from the German Empire. In Florence, the Medici family came to power, although entirely dependent on the Habsburgs. In 1559, France recognized Spanish possessions and influences at the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis. At that time only the Republic of Venice remained independent.

In addition to the major political changes, the cultural boom of the Renaissance also came to an end. In addition, the Counter-Reformation led to a reform of the Church in Europe that eliminated the Catholic Church from participating in the struggle for secular authority, but instead concentrated on becoming the world's religious and moral superpower. Yet the Roman Catholic Church remained a power of significance by making alliances with Roman Catholic powers and powerful monastic orders such as e.g. the Jesuits.

At that time, Italy was economically ruined by, among other things, wars and the shift of world trade to the coasts of the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Due to the decline of Germany as an economic hinterland, Northern Italy was hit hard. In fact, only the Republic of Venice survived these harsh economic times.

In the 17th century, the political rise of Savoy was an important development, as it would become the strongest state in Italy in all respects by the 18th century. After the War of the Spanish Succession, Duke Victor Amadeus was assigned Sicily and immediately assumed the title of king. In 1720 he acquired Sardinia in exchange for Sicily, which was ceded to Austria. The War of the Spanish Succession also caused changes in the south of Italy. Austria got Sardinia and Naples and in 1738 these two areas were given to a representative of the Spanish House of Bourbon. The condition was that the southern Italian empire would never again fall to the Spanish king. Milan had already passed into Austrian hands in 1713 and the united duchies of Parma and Piacenza had belonged to the Spanish House of Bourbon since 1748. It is clear that in the 18th century there was little left of any Italian political or military power except Tuscany. In 1768 Corsica, a long Genoese possession, was transferred to France. The only positive thing was that Italy was able to recover in the cultural field, a development that would also occur in political and social fields in the 19th century.

In 1796, Napoleon entered Italy and took with him the ideas of the French Revolution. Politically Italy was completely turned upside down,

Savoy (with Piedmont) was annexed to France; in the Po Valley, the Cis and Transpadan Republics were united to form the Cisalpine Republic; Genoa became the Ligurian Republic; the Papal State became the Roman Republic; Naples (without Sicily) became the Parthenopean Republic and Venice was added to Austria. Papal status was restored in 1799 and a Bourbon king returned to Naples. In 1801, Tuscany was made the Kingdom of Etruria and the Cisalpine Republic into the Italian Republic. In 1805 the Italian republic, enlarged with Venice, was proclaimed Kingdom of Italy under Napoleon I Bonaparte; Naples became a French vassal kingdom under Joseph Bonaparte in 1806 and replaced by Joachim Murat in 1808; Genoa and Parma were annexed to France. In 1807 France also annexed Etruria and in 1808 the Papal States.

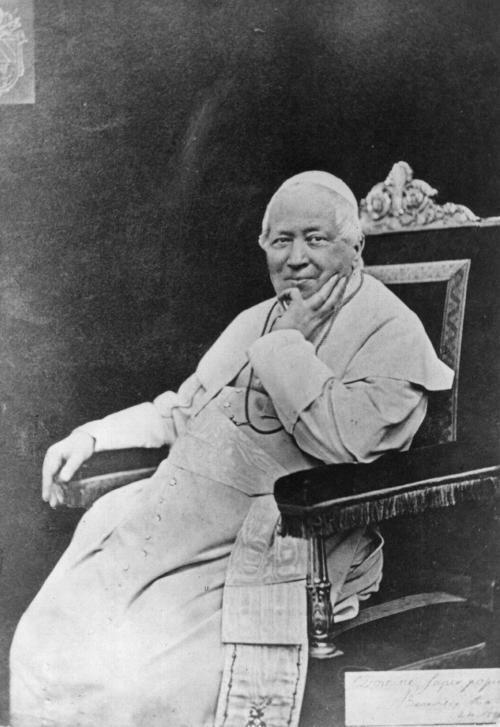

Italy Pius IX Photo:Public domain

Italy Pius IX Photo:Public domain

In 1815, the Restoration also began in Italy and the political division then became as follows: the kingdom of Sardinia / Genoa, Tuscany, Modena, Parma and Lucca (in fact Austrian vassal states), the Lombard-Venetian kingdom under direct Austrian sovereignty, the Ecclesiastical State, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the Principality of Monaco and the Republic of San Marino. Lucca joined Tuscany in 1847. In all these states, the old or new rulers adopted a strict regime of repression and reaction. The French institutions were cleaned up and the ancien régime was restored to its full extent. However, the development that had started under the influence of the French ideas and institutions could no longer be stopped. Resistance to the existing order continued and soon gained an ideological basis in liberalism. Expulsion of all non-Italian rulers and the formation of a single national Italian state on a modern basis became the common ideal and this movement was called the Risorgimento. In 1820 and 1821 there was actual resistance from, among others, the Carbonari, a number of societies that played a major role in the struggle for freedom in Italy, but also in other countries.

In 1830 the July Revolution made its mark in Italy and the status quo could only be restored with the help of Austrian weapons.

In 1846, the liberal Pope Pius IX was elected, and many placed their hopes in him. In the revolutionary year of 1848, constitutions were promulgated in Naples, Tuscany, Sardinia and the Papal States, and revolutions broke out in Milan and Venice, after which Charles Albert of Sardinia declared war on Austria. However, the Sardinians lost at Custozza in July 1848 and an armistice was signed. The revolution in Naples had meanwhile been suppressed. Shortly thereafter, the radicals successfully seized power in the Papal State. Pius IX had to flee and February 9, 1849, the Roman republic was proclaimed. In March 1849, Charles Albert resumed the fight against Austria, but after the defeat at Novara he resigned for his son Victor Emanuel II, who made peace with Austria on 9 August. In April, meanwhile, the French had launched an attack on the Roman republic in favor of the Pope. By the end of August 1849, the old order had been restored everywhere in Italy. Constitutions were abolished everywhere, except in Sardinia (with King Victor Emanuel), where Cavour came to the fore, who, both supported and thwarted by Garibaldi, achieved that on March 17, 1861, the independent kingdom of Italy could be proclaimed. The kingdom encompassed all of Italy, with the exception of San Marino and Venice and the core area of the Papal States. Monaco was separated from the Italian territory by the area distance of Sardinia from France in 1860.

The young state and its problems

Italy Victor Emanuel IIIPhoto: Public domain

Italy Victor Emanuel IIIPhoto: Public domain

Venice-Lombardy was not relinquished by Austria in 1859 due to the opposition of the French emperor Napoleon III, and in Rome French troops took Pope Pius IX into protection, who would not relinquish secular authority over the Papal State. The Italians took control of Venice by alliance with Prussia against Austria in 1866, even though the Italian troops were defeated in this war.

After the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Napoleon III withdrew his troops from Rome, so that territorial unity could be completed with the annexation of the capital in September 1870. Pius IX refused to accept the loss of his territory and afterwards relations with the Italian government remained difficult. It was not until 1929 that a concordat was established, recognizing the kingdom of Italy and papal sovereignty over Vatican City. Around that time, Italy became bicameral with a Senate appointed by the king and an elected Chamber. For the first decades, the authority of the government was undermined by the strife between the political parties - the liberals and the radicals - and the personal scandals of politicians. The most important political figures at this time were Agostino Depretis and Francesco Crispi. The financial policies of the various governments turned out badly because of he bad economic situation. Industry developed in the north, but the social conditions were terrible; the large landholdings in the south created a deep divide between the poor part of the population and the rich. It was therefore not surprising that many Italians emigrated, especially to the United States. This situation was a perfect breeding ground for the flourishing socialism and anarchism. King Umberto I, who had succeeded his father Victor Emanuel II, who died in 1878, was assassinated by an anarchist in 1900, after which Victor Emanuel III ascended the throne.

It was also during this era that Italy acquired its colonial possessions that appeal to the imagination: Eritrea (1882–1890), Italian Somaliland (1899–1905) and, after a war against Turkey, the Dodekánesos, and Libya. An attempt to subdue Abyssinia (Ethiopia) ended in a shameful defeat at Adoea in 1896. Relations with France were not very cordial at first, and Italy sought to link up with Austria and Germany. In 1882 Italy concluded the so-called Three-fold Covenant with these countries. Nationalist Italians, however, were not satisfied with the boundaries reached and claimed some areas inhabited in part by Italians: the French Nizza (Nice) and Savoy, Trent, Istria with the city of Trieste and Fiume, present-day Rijeka. This endeavor was called the "Italia irredenta". (Irredentism is the pursuit of annexation of areas under the sovereignty of a neighboring country but inhabited by a population closely related to the native community.)

When the First World War broke out, Italy initially remained neutral, because the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria had a defensive character. Nationalists, irredentists and republicans, however, preferred to cooperate with England and France. After the Allies pledged generous territory expansion by the Treaty of London, Italy declared war on Austria in May 1915 and on Germany in August 1916. There were actually no military successes to report, but in the peace of Versailles, Italy was rewarded with Istria and Trieste, Zara (Zadar) in Dalmatia and the whole of South Tyrol, which from then on would remain a point of contention between Italy and Austria. Initially declared a free state, Fiume was arbitrarily occupied in 1919–1920 by the poet Gabriele d'Annunzio.

Fascism and Mussolini

Italy MussoliniPhoto: Public domain

Italy MussoliniPhoto: Public domain

The end of the war, as elsewhere in Europe, brought Italy to the brink of collapse due to a weak liberal government and poor economic conditions. As a result, discontent grew and strikes and disturbances broke out and communist workers occupied a number of factories. The communists clashed with the fascist movement of Benito Mussolini, founded in 1919. In October 1922, the fascists organized a march to Rome, after which Mussolini was appointed Prime Minister by King Victor Emanuel. Mussolini initially headed a coalition cabinet, but in late 1924 he eliminated the opposition and has ruled like a real dictator ever since.

The government of the Fascist party, the Great Fascist Council, was given far-reaching powers, but rarely if ever met. Mussolini, who allowed himself to be called "duce" (= leader), had great influence on the composition of the Council. Authority was thus imposed from above, both economically and socially.

Mussolini wanted to make Italy a great power and therefore invaded Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935, which was annexed to the Italian colonial empire in May 1936. The League of Nations imposed some economic sanctions as a punishment, but they amounted to little. In the Spanish Civil War, Mussolini sided with the rebellious General Franco. With the allied regime of Adolf Hitler that came to power in Germany in 1933, the relationship was initially cool, sometimes even tense, because of German aspirations towards Austria. As a result of the war in Abyssinia, however, a rapprochement arose and in October 1936 a cooperation agreement was concluded, the "Axis Rome-Berlin". In the spring of 1939 Albania was occupied and annexed by Italy. Mussolini used his influence to acquiesce the British and French at the Munich Conference in 1938 in German demands against Czechoslovakia, but when the Germans also invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, his mediation was ineffective. On June 10, 1940, when the French army had already been defeated, Italy declared war on Britain and France in the hope of realizing its claims to Nice, Corsica and Tunisia. During the war itself, the Italian army turned out to be of dubious quality again and the war against Greece, which started at the end of 1940, could only be settled in April 1941 thanks to German help. In East Africa the Italians were no match for the British and the capital of Ethiopia, Addis Abeba, fell April 6, 1941. In Libya the Italians were still helped by the German field marshal Rommel, but the British won under Montgomery after the Battle of El Alamein in October 1942. On July 10, 1943, the Allies landed in Sicily with the United States, and on July 25, Mussolini was deposed by the Great Fascist Council. His successor, Marshal Badoglio, signed an armistice with the Allies on September 3 and declared war on Germany on October 13, 1943. On September 8, 1943 the Allies landed at Salerno. The battle for Italy was completely taken over by the Germans, who were slowly pushed back to the north, after which Rome was liberated on June 4, 1944. In Northern Italy, Mussolini, who was freed from captivity by the Germans on 12 Sept. 1943, proclaimed the Italian Social Republic, and he returned to the extreme socialist politics of his early years. On April 29, 1945 the German armies capitulated; Mussolini had fled the day before but was seized by resistance fighters and murdered. Italy remained officially occupied by the Allies until January 1, 1947. In the peace ratified on February 10, 1947, the country lost its colonies and had to cede Dalmatia, Fiume, Istria and part of the province of Venice to Yugoslavia and Greece received the Dodekánesos. The zone of Trieste, placed under international administration, returned mostly to Italy on October 25, 1954, and a final agreement was reached with Yugoslavia in 1976.

The Italian Republic

Italy De GasperiPhoto: Publc domain

Italy De GasperiPhoto: Publc domain

After the war, the big question was again of Italy should become a monarchy or a republic. Victor Emanuel III, compromised by his positive attitude towards fascism, tried to save the throne by abdicating on May 10, 1946 in favor of his son Umberto II, but the Italians spoke in a referendum on June 2 1946 by 12 to 10 million votes for the republic. On the same day, a constitutional assembly was elected, in which the left and right received about the same number of seats. The Christian Democrat De Gasperi, who had formed a government with socialists and communists (PCI) in December 1945, remained prime minister.

In May 1947 the left parties left the government and the communists under Togliatti together with the left socialists under Nenni (PSI) united to form a Popular Front, which, with the support of the trade unions, shook the government through strikes and disturbances. The April 1948 parliamentary elections, thanks in part to the stance of the Vatican and the United States, yielded an absolute majority for Democrazia Cristiana (DC), ensuring the continued existence of a democratic and closely linked regime and affiliation with NATO and the European Community could be realized.

In the 1953 elections, the Democrazia Cristiana lost its absolute majority and relied on the support of coalition partners on both the right and left. This, of course, came at the expense of political stability and led to rapidly alternating cabinets led by right-wing and left-wing Christian Democrats. The 1958 elections brought gains to the Christian Democrats and the Nenni Socialists (named after party chairman of the socialist party Pietro Nenni), but this did not change the confusing situation.

Changing coalitions

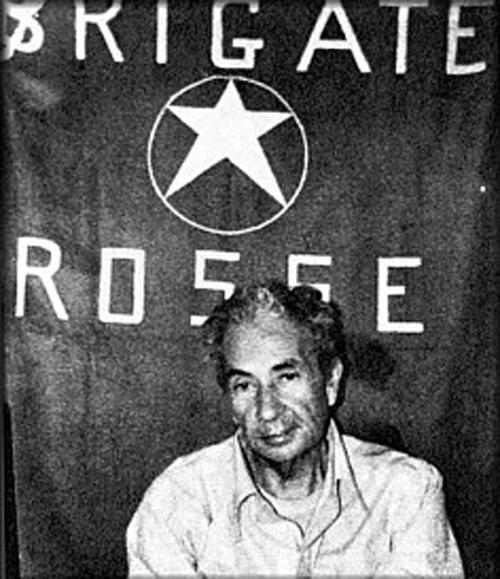

Italy Aldo MoroPhoto: Public domain

Italy Aldo MoroPhoto: Public domain

The 1963 elections brought some clarity. The Christian Democrats lost considerably while the Communists won more than a quarter of the vote. The Christian Democrats were now forced to open to the left to keep the communists out of government. This became possible after the Nenni socialists severed their ties with the communists for good.

In 1963, the party secretary of the Christian Democrats, Aldo Moro, managed to form a coalition government between the Christian Democrats, the Social Democrats, the Nenni Socialists and the Republicans. This coalition remained in power until the elections of May 1968, but was not followed up because the socialists lost many votes to the communists and entered the opposition. There was no other solution but to form a minority cabinet that, however, already resigned in November of that year.

Another cabinet of Christian Democrats, Republicans and Socialists followed under Mariano Rumor, which led to the fall of the cabinet in July 1969 after a split in the Socialist Party.

This was followed by a democratic minority government and a center-left coalition again under Rumor, which fell after only a few months.

His successor and fellow party member Colombo faced widespread social unrest, growing extremism and terrorism and was forced to resign in January 1972 due to the continuing disagreement between the coalition partners. The prime minister of an interim cabinet, Giulio Andreotti, decided early elections and a government of Christian Democrats, Social Democrats and (conservative) liberals led by Andreotti was established in June 1972. In July 1973 the center-left coalition under Rumor was restored. In November 1974, after enduring two cabinet crises, Rumor's government had to make way for a Moro cabinet made up of Christian Democrats and Republicans.

In June 1975 the communists received almost 39% of the vote in the parliamentary elections as a result of the many corruption scandals among the other parties. International relaxation between East and West ensured that the communists came back into the picture. At that time, however, it was impossible to form coalitions between the different parties and in July 1976 Andreotti was forced to form a minority government that was tolerated by all parties. However, the communists continued to strive for government responsibility.

In early 1978 Andreotti was forced to resign, after which the crisis was resolved by Aldo Moro. He ensured that the communists would in fact co-rule, but would not formally participate in the government and a Catholic-communist form of cooperation actually emerged. However, this soon came to an end on March 10, 1978 after the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro by the left-wing terrorist organization Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse). Catholic-communist cooperation then continued until January 1979, when the government was forced to resign.

It became increasingly clear to the communists that their compliant attitude in recent years has meant that they have lost more and more votes. Early elections were again held in June 1979, with the communists losing 4%. Two cabinets followed under Cossiga and Forlani, with varying combinations between Christian Democrats, Republicans, Liberals, Social Democrats and, since 1980, the Socialists.

These parties were eventually united in the "pentapartito", a five-party coalition. In 1981, the Christian Democratic Party had to relinquish its premiership under the influence of a scandal surrounding the Freemason Lodge P2.

Declining influence of Christian Democrats

In July 1981, Republican Italy's first non-Christian Democratic head of government, Spadolini, came to power. He would lead the government until November 1982. In July 1983, Bettino Craxi came to power and his government would become the longest-serving in post-war parliamentary history from July 1983 to March 1987. After the early 1987 elections, the situation basically remained the same and existing government cooperation continued. Up to and including June 1992, four cabinets succeeded each other in rapid succession.

Corruption and mafia

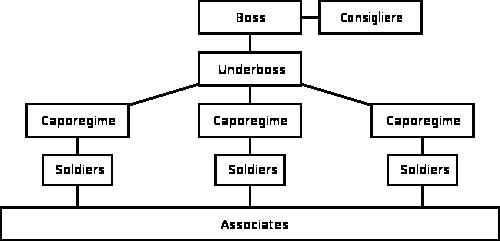

Italy Structure MafiaPhoto: Public domean

Italy Structure MafiaPhoto: Public domean

Giuliano Amato's new government took office in June 1992, but had to resign in April 1993 due to corruption. Well-known politicians involved in the dirty practices included Socialist leader Bettino Craxi and Minister of Justice Carlo Tognoli, all of whom had to resign. It was positive during this period that the mafia was tackled harder and harder and with success.

For example, the leaders of the Neapolitan Camorra and the chief of an important group of Sicilian mafia clans, Carmine Alfieri and Salvatore Riina respectively, were arrested. The latter was sentenced to life.

At the end of September 1995, the trial began against former Prime Minister Andreotti, who was also accused of having links with the Mafia. Meanwhile, in a referendum in 1993, the people had already decided to change the electoral system in order to reduce corruption.

The political spectrum expanded to include media mogul Silvio Berlusconi's party, Forza Italia, and the Lega Nord movement, which sought secession of the prosperous North. Berlusconi won a major victory in the March 1994 elections, but his government resigned at the end of 1994. He was increasingly associated with corruption and bribery practices and did not want to separate his business from his political activities. There were also several lawsuits against him and his business empire Fininvest.

The Lega Nord movement emerged in 1996 when their leader Bossi who proclaimed the independent state "Padania", an action that obviously could not be taken seriously. After several major defeats in midterm elections, Bossi backed down and announced that he did not want to secede unilaterally.

In 1998 Berlusconi was indicted and sentenced to prison terms, but due to lengthy appeal procedures and parliamentary immunity, there has been no actual imprisonment so far.

In June 1998, twelve politicians were convicted and imprisoned, including former Prime Minister Arnaldo Forlani and Lega Nord leader Umberto Bossi.

Center-left cabinets

Italy ProdiPhoto: Roosewelt Pinheiro/ABr CC 3.0 Brazil no changes made

Italy ProdiPhoto: Roosewelt Pinheiro/ABr CC 3.0 Brazil no changes made

Italy was in a serious economic trouble around that time. The Dini government, which pursued a successful austerity policy, was succeeded in May 1996 by a center-left coalition government, the so-called Olive Coalition, led by the progressive Christian Democrat Prodi. For the first time in post-war history, a center-left government came to power.

He immediately made a big effort by coming up with far-reaching proposals for constitutional reform and budget reform. He also pursued rapid entry into the European Monetary Union (EMU) through far-reaching austerity plans and restructuring proposals. The latter was successful and Italy was allowed to join the EMU on 1 January 1999.

The political reforms did not get off the ground because of disagreements within the special parliamentary committee in which both the Senate and the House of Representatives were represented.

Prodi led a minority government but was regularly abandoned by the radical communist PRC, and even often remained in power thanks to the opposition. In October 1998, the government was sent home by parliament after the PRC rejected the new budget proposals.

Prodi was succeeded by PDS leader Massimo d'Alema, who concluded a coalition agreement with, among others, the old Olive coalition. The Prodi line was continued, but soon there was division within the coalition about the course to follow. In March 1999 Prodi was appointed President of the European Commission. However, he continued to interfere in Italian politics and in October 1999 made D'Alema a proposal to resume cooperation. Cossiga's center-right UDR would then be discharged and the Democrats' participation in the government could create a more stable coalition. D'Alema wanted to, but did not dare to risk a vote of confidence in parliament.

In December, D'Alema resigned and formed a new cabinet (with the Democrats and without the UDR), which gained the confidence of parliament on December 23.

21st century

Midterm regional elections in April 2000 yielded a major victory for the right-wing parties, further weakening D'Alema's position. He again offered the resignation of his government, and on April 26, Giulio Amato was asked to form a new government based on the same coalition. This coalition received parliamentary approval on 28 April.

Amato made a name for itself by implementing rigorous privatizations in 2000, including the airline Alitalia, Telecom Italia and the Banca Commerciale Italiana. However, divisions within the center-left coalition continued and new parliamentary elections were held on May 13, 2001. These elections were gloriously won by Silvio Berlusconi's Freedom Alliance and lost by Francesco Rutelli's Olive Coalition. On June 11, 2001, Berlusconi was sworn in as prime minister and deputy prime minister became post-fascist Gianfranco Fini. The leader of the Lega Nord protest party, Umberto Bossi, was also given a ministerial post.

At the end of December 2002, Prince Vittorio Emanuele returned to Italy after 56 years of exile. The Italian government gave the last king's son permission to set foot on Italian soil in November. The members of the House of Savoie have lived in Switzerland in recent years and have often tried before the Court of Strasbourg to obtain permission to return on the basis of human rights. The family was exiled in 1946 because Vittorio's father had collaborated with the fascist regime.

The parliamentary elections held in early April 2006 were won by Romani Prodi. An attempt by the Berlusconi government to enforce a recount of invalidated votes failed. The Court of Cassation ruled that no irregularities had been found in the elections that affected the result. Prodi eventually won the election with a narrow majority of 25,224 votes (out of a total of more than 38 million voters).

Thanks to a bonus arrangement for the center-left coalition, the win secured a fairly comfortable 64-seat majority in the House of Representatives. In the Senate, Prodi had only two more seats than the center-right. Finally, the government fell on January 24, 2008 after the small party Udeur (3 seats in the Senate) led by Minister Mastella withdrew its support. With this, the government could no longer fall back on a majority in the Senate and Prodi had to offer his resignation to President Napolitano.

President Napolitano decided, after failing to form an interim government, to call elections for April 2008.

Italy BerlusconiPhoto: Ricardo Stuckert/PR CC 3.0 Brazil no changes made

Italy BerlusconiPhoto: Ricardo Stuckert/PR CC 3.0 Brazil no changes made

After the fall of the Prodi government, the right-wing bloc was still headed by Silvio Berlusconi.

The left-wing bloc was led by Walter Veltroni, ex-mayor of Rome, and party leader of the Partito Democratico (PD). A real game to the left of the middle, which should replace Ulivo. The consituent parts of the PD (including the largest such as DS and Margherita) have committed themselves to a merger into the new PD.

On the center-right side, a new large party has also emerged, in which Forza Italia and Alleanza Nazionale, among others, have merged. Led by Silvio Berlusconi, Il Popolo della Libertà took on Veltroni's PD in the 2008 parliamentary elections. Berlusconi won these elections by a big lead over Veltroni. He is now the new Prime Minister of Italy for the third time. In November 2008 Italy fell into recession due to the credit crisis. In April 2009 there was a major earthquake in Abruzzo. In March 2010 Berlusconi won the regional elections.

Italy Georgio NapolitanoPhoto: Roberto Ferrari CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Italy Georgio NapolitanoPhoto: Roberto Ferrari CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

In the years 2011 and 2012, Italy is sinking deeper economically. Several lawsuits are pending for corruption against Berlusconi. When he is finally convicted in December 2012, his party pulls the plug on the coalition government led by the technocrat Mario Monti. Giorgio Napolitano decided to stand for re-election after the election of a new president in April 2013 ended in an impasse. His re-election was confirmed by an absolute majority. Enrico Letta takes office as prime minister of a coalition. In December 2013, the mayor of Florence Matteo Renzi becomes the new strongman of the center left party. In February 2014, Letta leaves the field for Renzi, who says he will help Italy out of the economic problems. Giorgio Napolitano resigns in January 2015, Sergio Mattarella succeeds him. Many refugees will arrive in Southern Italy in 2015 and 2016. In November 2016, Renzi resigns after his constitutional reforms were voted down in a referendum. He will be succeeded by coalition partner Paolo Gentiloni. In October 2017, residents of wealthy Veneto and Lombardy voted for more autonomy in a non-binding referendum.

Italy Giuseppe ContePhoto: Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri CC 3.0 no changes made

Italy Giuseppe ContePhoto: Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri CC 3.0 no changes made

Giuseppe Conte was sworn in in June 2018 as prime minister of Western Europe's first populist government, whose aim was to cut taxes, boost welfare spending and overhaul European Union rules on budgets and immigration. Mr Conte, a law professor, was the choice of the far-right League and the radical 5-Star Movement, which formed a governing coalition and ended three months of political deadlock following inconclusive elections.

In August 2019, League leader Matteo Salvini withdrew from the government in the hope of triggering early elections and boosting his party's position in parliament.But the 5-Star Movement and centre-left Democratic Party frustrated this plan by agreeing a new coalition without the League, with Giuseppe Conte retaining his position as prime minister. In 2020 Italy was severely hit by Corona with devastating effects on the already troublesome economy.

Mario Draghi, ItalyPhoto: World Economic Forum CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Mario Draghi, ItalyPhoto: World Economic Forum CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Conte will step down in January 2021 and is succeeded in February by the non-party former president of the Central European Bank, Mario Draghi, who will lead a cabinet of national unity with many technocrats in his cabinet. His main task remains to lead the fight against the pandemic.

Italian presidential election is being held since 24 January 2022. The President will be elected by a joint assembly composed of the Italian President and regional representatives. The election process started on 24 January 2022, and is expected to take multiple days. Despite not standing for re-election, Sergio Mattarella agreed to another term as president at the express request of the government.

Giorgia Meloni became Italy's female prime minister in October 2022 at the head of a coalition including her right-wing populist Brothers of Italy party, the far-right League and ex-prime minister Silvio Berlusconi's Forza Italia.

Sources

Elmar Landeninformatie

Wikipedia

CIA - World Factbook

BBC - Country Profiles

Last updated February 2026Copyright: Team The World of Info