ALGERIA

History

History

History

Prehistory and antiquity

Hundreds of millions of years ago, the Sahara was covered with large inland seas. Decades ago, the situation had changed completely and the Sahara was an even bigger desert than it is today. Evidence of human presence in present-day Algeria dates back to 1.8 million years ago;in 1992 the Oldowan hand tools were found near Ain Hanech in northern Algeria and fossils of a 700,000-year-old Homo erectus near Ternefine. Tens of thousands of years ago, the Sahara transformed into one large oasis with extensive forests, lakes and a pleasant Mediterranean climate. At the time, mainland Europe was experiencing an ice age.

Oldowan Implements, AlgeriaPhoto: Didier Descouens CC 4.0 International no changes made

Oldowan Implements, AlgeriaPhoto: Didier Descouens CC 4.0 International no changes made

The climate could have been the reason that 15,000-10,000 years ago different groups came together and a Neolithic (new stone age) culture with agricultural techniques and a (semi) permanent habitation arose. Petroglyphs and sculptures, found in Tassili n'Ajjer National Park, among others, are important sources that tell something about the way of life in those bygone times.

Sleeping Antelope, petroglyph found on the Tassili n'Ajjer Plateau, Southeast AlgeriaPhoto: Linus Wolf CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Sleeping Antelope, petroglyph found on the Tassili n'Ajjer Plateau, Southeast AlgeriaPhoto: Linus Wolf CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

It is believed that this Neolithic population is the origin of the Berbers, the original indigenous people of North Africa. By the time the Phoenicians, a seafaring people from what is now Lebanon, reached the coasts of what is now Algeria, the Berber tribes, made up of nomadic herders, hunters, and farmers, had settled permanently in Algerian territory.

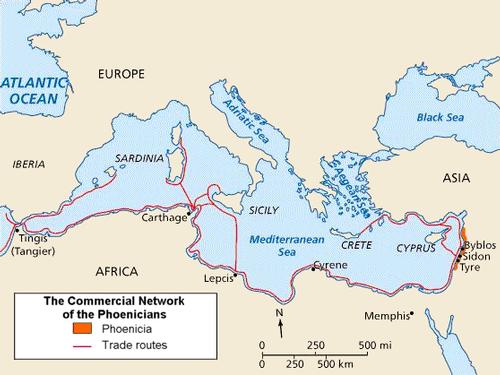

Around 1000 BC. attracted by the strategic location of the Algerian coastal area, the Phoenicians founded the first trading posts that engaged in trade to Spain, but did nothing to further develop the occupied Algerian territory. That did not happen until the 7th century BC. with the construction of permanent settlements such as Hippo Regius, Saldae and Cesare. Of much greater importance, however, would be the foundation of Carthage, located in present-day Tunisia, in 814 BC. to be. Within a few centuries, Carthage would grow into a powerful, independent trading empire, although the Phoenicians still established settlements on the Algerian coast. Around the 4th century BC. Carthage controlled the North African coast from Tripolitania (now Northwest Libya) to the Atlantic Ocean. Even now little attention was paid to the Berber hinterland, much more important to Carthage's interests were a series of safe havens and the protection of the trade routes. The Berbers were more or less forced to move to the mountains and the desert, pay taxes and serve in the Carthaginian army.

Phoenician trade routesPhoto: Yom CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Phoenician trade routesPhoto: Yom CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

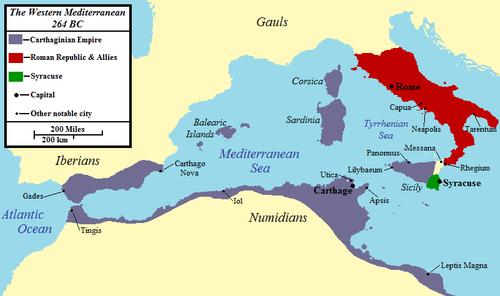

Carthaginian and Roman Empire in 264 BCPhoto: Jon Platek Besvo CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Carthaginian and Roman Empire in 264 BCPhoto: Jon Platek Besvo CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

At the time, the Roman Empire was on the rise, and Carthage was inevitably affected, ultimately resulting in the Punic Wars and the downfall of Carthage. In the First Punic War (263-241 BC) between Carthage and the Roman Empire, Carthage lost many naval battles, was forced to destroy Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, but managed to consolidate its position in North Africa for the time being. In 204 BC. a Roman army landed at Utica (now in Tunisia), Carthage capitulated and lost its fleet and all its overseas territories. The decline of Carthage increased the power of the Berber kingdoms, including the kingdom of Numidia in northeastern Algeria, which was founded in the 2nd century BC. from the capital Cirta Regia (now the city of Constantine) was led by King Massinissa. The severely weakened Carthage still somewhat held out against the attacks of Massinissa, but a new attack by the Romans in 146 BC. marked the end of the Carthaginian empire. Meanwhile, Massinissa was in 148 BC. died and the Berber kingdoms were left in chaos.

Massinissa (c.239 - c.148 v.Chr.)Photo: Public domain

Massinissa (c.239 - c.148 v.Chr.)Photo: Public domain

After the takeover of Carthage, the Romans soon controlled the entire north of present-day Libya. and then turned west, where the Numidian ruler Jugurtha, the grandson of Massinissa, slaughtered a number of Romans who aided Adherbal, a Roman ally who defended the city of Cirta Regia against the Numidis. Jugurtha managed to fend off a number of attacks from the Romans, but was finally destroyed in 105 BC. betrayed by Bocchus I, king of the Berber empire of Mauretania. The newly acquired land, intended to function as the granary of the Roman Empire, was given to settlers by the Romans, and in 46 BC. Roman Emperor Julius Caesar defeated the last Jumidian king, Juba I. Bocchus II of Mauretania died in 33 BC. and left his empire to the Romans, who appointed Juba II, who was married to the daughter of Mark Anthony and Cleopatra, as ruler. After the murder of Juba's son, Ptolemy, the kingdom was divided in two, Mauretania Caesariensis, whose capital was Caesarea (now in Algeria), and Mauretania Tingitana, whose capital was Tingis (now Tangier, Morocco). From this time to the fall of the Roman Empire in the 4th century AD. the Algerian part was a stable and integral part of the Roman Empire and several settlements were founded, Tipasa (now: Tipaza), Cuicul (now: Djemila), Sitifis (now: Sétif) and Thamugadi (now: Timgad), the largest Roman settlement ever built in North Africa. In total, the Romans founded more than 500 settlements in Northern Algeria.

Location Mauretania Caesariensis and Mauretania TingitanaPhoto: Kazvorpal CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Location Mauretania Caesariensis and Mauretania TingitanaPhoto: Kazvorpal CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

However, this period of prosperity was at the expense of the Berbers, who lost agricultural land as well as more and more autonomy. The Berbers revolted regularly, and the Romans' response was the construction by Emperor Trajan (AD 53-117) of a number of fortresses to mark the southern border of the Roman area. The southernmost point of Roman Algeria at that time was Castellum Dimmidi (currently Messaad), some 250 km south of present-day Algiers. After the conversion in 313 of Emperor Constantine the Great (ca. 280-337) to the ever-expanding Christianity, many Romans but also Berbers in Algeria followed his example. At that time, Saint Augustine became bishop of Hippo Regius (now Annaba in Northeast Algeria). In the 4th century, one tribal uprising followed another, a faint sign that the end of Roman Algeria was approaching.

Roman ruins in Djémila, Northern Algarve Photo: Yelles CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Roman ruins in Djémila, Northern Algarve Photo: Yelles CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Middle Ages and the arrival of Islam

In the 5th century, Algeria was conquered by the East Germanic Vandals under the leadership of King Geiserik. In 429 Geiserik decided to move with the entire Vandal people from Spain to North Africa. He advanced to Hippo Regios and during the siege of that city Saint Augustine lost his life. Soon all of northeastern Algeria was in the hands of the Vandals, and by the middle of the century the western Mediterranean was practically wiped from the hands of the ships of Geiserik and the western Roman Empire.

The Vandal Geiserik conquers and loots Rome at June 455Photo: Public domain

The Vandal Geiserik conquers and loots Rome at June 455Photo: Public domain

North Africa was not really colonized by the Vandals, they were more interested in looting and more overseas conquests. Outside the fortresses of the Vandals, the Berber tribes took back control, rebelled and founded a number of kingdoms again. Meanwhile, the Byzantine emperor Constantine the Great had revived the Eastern Roman Empire and planned to reclaim the western half of the empire as well. The Roman general Flavius Belisarius (500-565) defeated the Vandals in 533, but in fact got no further than control of a number of coastal towns and some inland settlements. The Berbers continued to resist the invaders and Byzantium did not make itself popular by massively increasing taxes.

Vandals migration routesPhoto: Public domain

Vandals migration routesPhoto: Public domain

Lack of Byzantine control made it easy for Arab cavalry to take possession of North Africa. Egypt was conquered from Damascus in 640 by the soldiers of Amr ibn al-As, but under army leader Uqba bin Nafi al-Fihri, the Islamization of North Africa was only beginning to take shape. From 669 onwards, he moved west through North Africa, founded the first major Muslim city in the Maghreb, Al-Qayrawan, present-day Kairouan in Tunisia, and is said to have even reached the Atlantic Ocean. In 698 the last vestiges of Byzantine rule had disappeared and as early as 712 the entire region was removed from Andalucia in Spain to the Levant, an area in the west of the present-day Middle East, in the hands of the Umayyad caliphs. Uqba's successor, Abu al-Muhajir Dina, was responsible for introducing Islamic law in Algeria, converting the Berbers, and appointed Umayyad governors who ruled Eastern Algeria. Despite the Berbers' conversion to Islam, this people remained loyal to its own culture and resisted the Arabization of its area. The interior was again ravaged by Berber uprisings, the largest of which took place in 740 from Morocco and defeated the Umayyad armies west of Al-Qayrawan.

Caliphate of the UmayyadsPhoto: Gabagool CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Caliphate of the UmayyadsPhoto: Gabagool CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In 750, the caliphate moved from the Umayyads in Damascus to the Abassids in Baghdad and the western Muslim area, North Africa and Spain, split from the eastern Muslim area. Eventually three Islamic kingdoms arose in North Africa, the Idirissids from Fez in Morocco (788-985), the Aghlabids from Kairouan in Tunisia (800-909) and the Rustamids from the Algerian province of Tiaret (777-909). From 761 to 909 much of Central and Northern Algeria was ruled by Abd al-Rahman ibn Rustum. The Rustamids were enlightened rulers of Algeria, they were deeply interested in art and science, were righteous and did not allow corruption. However, they forgot to build a strong army and were easily expelled by the caliphate of the Fatamids, followers of the Isma'ilite movement within Shia Islam, who ruled from 909 to 1171. In 969, the Fatamids marched with a Berber army into Egypt, conquered the then capital Fustat and founded a new capital al-Qahira, present-day Caïro. Before they moved to Egypt, power in North Africa was transferred to the Berber Zirids (972-1148), founders of Algiers, who made Algeria a regional power for the first time in history. As far as religion was concerned, they were anti-Shia and turned to the anger of the Fatamids to the Sunni direction of Islam. Tribes from Upper Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula were called upon to fight the Zirids and by 1148 Northern Algeria was fully Arabized.

Empire of the Fatamids at the peak of powerPhoto: Gabagool CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Empire of the Fatamids at the peak of powerPhoto: Gabagool CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In the 10th century the power of the Idrissids in Morocco (788-985) evaporated, but soon a new Berber power emerged from the Sahara. Inspired by the theologian Abdullah bin Yasin, an alliance of Berber tribes, the Sanhaja confederation, was formed. The Sanhaja Confederation started a series of wars in the Southern and Central Sahara to control the trans-Saharan (gold) routes threatened by the Zenata Berbers from the north.

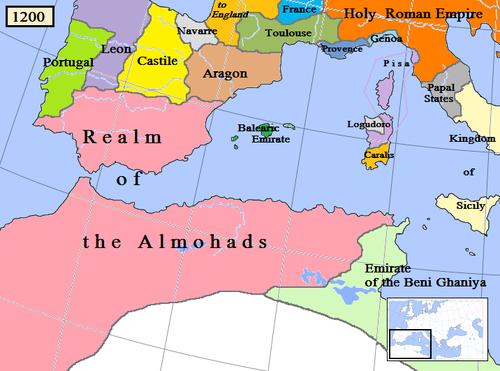

The Sanhaja were called 'al-mulathamin' because of their veils and 'al-murabitin' because of their fortresses, later known by the derived name Almoravids. In 1062, Almoravid leader Youssef bin Tachin, with Marrakesh as its capital, founded an empire that stretched at its peak from Senegal to Zaragoza in northern Spain and east to Algiers. Among the Almoravids, scientists and philosophers were highly regarded, other faiths were tolerated and women played an important role in society. Later still, the Almoravids allowed themselves more and more freedoms that were at odds with the principles of Islam. Another Moroccan dynasty, that of the Almohads, had had enough and in 1146 Marrakech was conquered from the Almoravids and the last Almoravid king, Ishaq ibn Ibrahim, was killed. Not long after, in 1160, the whole of Algeria was in the hands of the Almohads and eventually the Almohad Caliphate ruled the Maghreb and southern Spain.

Empire of the Almohads in ca. 1200Photo: Gabagool CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Empire of the Almohads in ca. 1200Photo: Gabagool CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

However, the success went too quickly and internal strife meant that the caliphate was almost over in 1244 at the hands of the Merinids, a Moroccan tribe of Zenata-Berbers. In Spain the Almohads were succeeded by the Nasrids, in Tunisia and parts of Libya by the Hafsiden and in Algeria by the Zianiden or Banu Abd al-Wad. The Zianids later formed a coalition with Granada in Spain, but had to bow twice to the power of the Merinids in the 14th century and were a puppet state of the Hafsids in the 15th century.

Ottoman Algeria

In 1492 the Muslims (Moors) were expelled from Spain and Spain became the leading nation in North Africa, aided by a series of fortresses or 'presidios' built along the coast to provide money from passing ships and from domestic tribes. In Algeria, such fortifications were founded in Mers el-Kebir (1505), Oran (1509), Tlemcen (1510) and Algiers (1510). The Spanish Fort of Santa Cruz still exists.

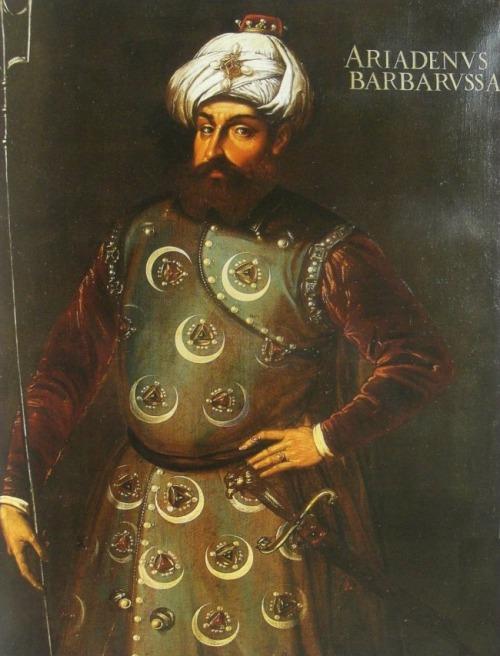

At the same time, the Turkish pirate Barbarossa and his brother Arudj were allowed to settle on the Tunisian island of Djerba. Arudj conquered Algiers from the Spaniards from Djerba in 1515, but Algiers was recaptured in 1518 and Arudj did not survive. Barbarossa then decided to unite with the Ottoman Turks in order to better defend his possessions. And indeed, with the help of the Ottomans, Barbarossa managed to control the entire Algerian coast, from Oran to Constantine. Clever as he was, he offered Algiers to the Ottomans, and received Algiers as a reward for being appointed governor there by the Ottomans. Later he was also appointed admiral of the Ottoman fleet. Algiers, meanwhile, had become the main base of support for the Ottomans in North Africa.

Barbarossa Khair ad-Din Pasha (ca. 1475-1546)Photo: Public domain

Barbarossa Khair ad-Din Pasha (ca. 1475-1546)Photo: Public domain

The Spaniards tried hard to break the increasing power of the Ottomans, but in 1551 Tripoli fell to the Ottomans, in 1574 Tunis suffered the same fate. Together with Algeria, these three provinces were governed by a pasha, assisted by a 'dej', an administrative governor, and a 'bej', a military governor and commander-in-chief of the Janissaries, or 'ojaq', soldiers. In Algeria, real power was in the hands of the dej, the pasha had more of a ceremonial function. The dej's power in Algeria disappeared in 1671, when the last dej appointed by the Ottomans was assassinated. During the Ottoman period, Algeria was divided into three provinces with the capitals Constantine, Médéa (south of Algiers) and, since 1791, Oran. Inland, Berber tribes retained a certain autonomy. In retrospect, the entire Ottoman rule did not amount to much, for Algeria, Tunisia and Tripolitania acted as they saw fit and often even fought among themselves. Barbary piracy was also still flourishing and played a major role in the local economy. European powers often tried to do something about this, but that still ended in failure.

Ahmed I (1590-1617) established a trade relationship between Algeria and the NetherlandsPhoto: Public domain

Ahmed I (1590-1617) established a trade relationship between Algeria and the NetherlandsPhoto: Public domain

French Algeria

The French presence in North Africa began in 1830 with a blockade and attack on Algiers. The reason for this would have been that the Algerian dej would have insulted the French consul, but the real reason was most likely that King Charles X (1757-1836) needed military success to disguise his weak position in France. Within three weeks of the landing of over 30,000 French troops, Algiers was captured and a period of murders, rapes and mosques destroyed. Algeria was officially annexed by France in 1834 and the colony was from that time ruled by a 'régime du saber' (government of the sword) headed by a military governor-general. In 1832 Oran and in 1836 especially the bej van Constantine revolted against the French. Constantine managed to defeat the French, but a year later the French conquered Constantine again.

Great man in the conflict with the French, and later proclaimed a national hero, was Abdelkader ibn Muhieddine, a sharif (descendant of Mohammed's daughter Fatima), who was recognized in the Treaty of Desmichels (1834) and took control of Western and Central Algeria. However, this got out of hand, because at the end of 1838 two thirds of Algeria was under Abdelkader's control. As it were, a separate state emerged with its own legal and administrative system.

Abdelkader ibn Muhieddine (1808-1883)Photo: Etienne Carjat in the public domain

Abdelkader ibn Muhieddine (1808-1883)Photo: Etienne Carjat in the public domain

France did not let this go by itself and by 1840 there were already more than 100,000 French troops, led by the French General Thomas-Robert Bugeaud, in Algeria, about a third of the entire French army. In the six-year battle between Bugeaud's and Abdelkader's troops, the latter was forced to flee to Morocco in 1844, where he enlisted the help of Sultan Abd ar-Rahman. That help came but did not affect the outcome of the battle, in 1846 the Algerian/Moroccan army was defeated at Isly. Abdelkader surrendered to the French and in return the promise that he could live somewhere in the Middle East. However, he spent until 1852 in a number of French prisons, after which he was allowed to leave and settled in Damascus. In 1847 Bugeaud had conquered most of Algeria and was proclaimed Governor General, but it was not until 1871 that Northern Algeria was defeated after fierce resistance from the Berbers in the Kabylie region. In 1848, Algeria was officially considered part of France. Also further south, the French conquered more and more land, mainly from the Tuaregs, and in 1902 Algeria's current borders were established.

Meeting between General Bugeaud and some Algerians in 1846 Photo: Public domain

Meeting between General Bugeaud and some Algerians in 1846 Photo: Public domain

During the first fifty years of the French occupation, besides French, many Italian, Maltese and Spanish colonists (colons), and even Sephardic Jews, settled in Algeria. And this was all at the expense of the native population and its culture. A poignant example was the transformation of the Djemaa el-Kebir mosque in Algiers into the Saint Philip cathedral. This created more and more frictions between the French government and the so-called 'pied-noirs', descendants of the colonists mentioned above.

Symbol of the Pied NoirsPhoto: Public domain

Symbol of the Pied NoirsPhoto: Public domain

In 1871, the Kabyli an uprising that spread across the country. The French hit back hard, taking more tribal lands, even higher taxes, and military oppression even more oppressed. Algerians were also imprisoned without trial and education for the Algerian children barely got off the ground. However, a small number of upper-class Muslim children were sent to French universities, the so-called 'volués'. France later regretted this, because these students soon began to wonder why the freedoms that applied to France did not apply to their own country, Algeria. From this group of highly educated critical students a nationalist movement would grow. And the more than 170,000 Algerians who fought for the Allies in World War II also had increasing doubts about the French occupation of Algeria. One of the popular leaders at the time was Khaled ibn Hashim (1875-1936), a grandson of Abdelkader ibn Muhieddine, the former military and religious leader of Algeria. He had also studied in Paris, had been an officer in the French army and had fought in the First World War.

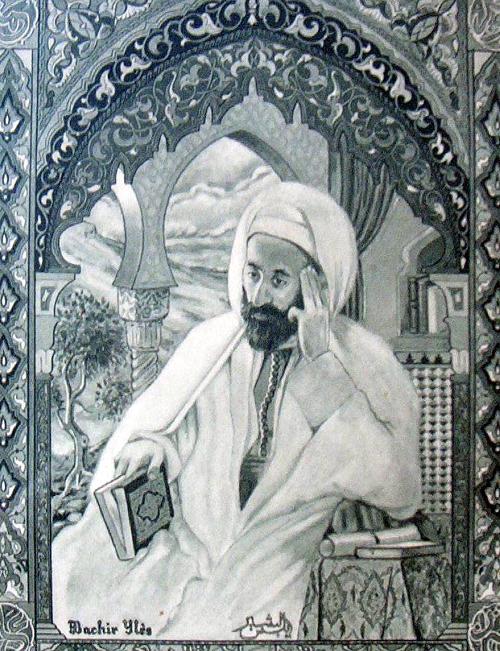

The call by mostly young Algerians for independence and at least a much greater autonomy was getting louder and there were cautiously also formed some nationalist groups. In France, this culminated in 1937 with the foundation of the Parti du Peuple Algérien under the leadership of Messali Hadj (1898-1974), demanding full independence, followed by the establishment of the Association, previously founded by Sheikh Abd al-Hamid ben Badis. des Uléma Musulmans Algériens, a more religiously oriented alliance, in Algeria.

Abd al-Hamid Ben Badis (1889-1940)Photo: Yelles, M.C.A CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Abd al-Hamid Ben Badis (1889-1940)Photo: Yelles, M.C.A CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Algeria has also suffered from World War II, and was also important in that the headquarters of Charles de Gaulle's free French and the British and American war planners from Algiers devised their plans of attack. Winston Churchill and the American General Eisenhower were often to be found in Algiers from 1943. The port of Annaba was often bombed by the Germans in the period 1942-1943. At the start of the war, many French battleships lay in the naval port of Mers el-Kabir of Oran. When France capitulated to the Germans in 1940, the British attacked the French ships to prevent them from falling into German hands. However, this cost the lives of about 1,300 French sailors.

Anti-aircraft gun during a German air strike on AlgiersPhoto: Public domain

Anti-aircraft gun during a German air strike on AlgiersPhoto: Public domain

Algerian War of Independence (1954-1962)

Both secular and Islamic nationalist groups were popular in Algeria, but would later face each other. After World War II, French repression continued in Algeria, even though the President of France, Charles de Gaulle, decided to give certain groups of Muslims French citizenship. However, this was considered far from enough, and an uprising ensued near Sétif, killing more than a hundred Europeans. Bloody reprisals from the French followed, more than 45,000 Algerian Muslims (according to historians it would be 'only' about 6,000 dead) were killed by the French. In 1947, all Algerian Muslims were given French citizenship and the right to live and work in France. For the French, however, independence was still too far.

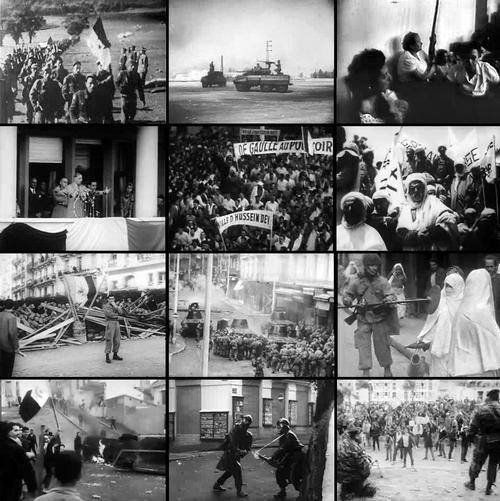

On November 1, 1954, a number of Algerian guerillas or 'maquisards' founded the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), with the aim to overthrow the French government in Algeria by military means and get the world community behind it through foreign diplomacy. Attacks on French government institutions followed and an appeal was made to all Algerians to join the fight "according to the principles of Islam." The answer of the French Minister of the Interior, the future President François Mitterand, was clear, 'the only negotiation is war'. The Algerian War of Independence was a fact at that time.

Algerian War of Independence Photo CollagePhoto: Public domean

Algerian War of Independence Photo CollagePhoto: Public domean

In addition to the French army as its opponent, the FLN also had to deal with cruel vigilante-like groups in the countryside, whose actions caused hundreds of thousands of 'colons' to flee to the capital Algiers. In an attempt to quell the revolt, De Gaulle decided to send Jacques Soustelle to Algeria as governor-general with favorable economic proposals for the ordinary Algerian. However, this gesture came too late, almost at the same time the FLN massacred 123 French civilians in August 1955 at Philippeville (near Constantine). The reaction of the French was again disproportionate: about 12,000 Algerians were killed and all-out war broke out. From 1956 the FLN was supported by Nasser's Egypt, in addition to the support of the former French colonies of Morocco and Tunisia. In response, the French built a barbed wire fence and watchtowers on the borders with Morocco and Tunisia. In the same year, the FLN launched guereilla tactics in Algiers and other cities, followed in 1957 by a national strike and hundreds of often night-time lightning strikes and ambushes on both military and civilian French targets. The 400,000-strong French army, but also about 150,000 'harkis', France-loyal Muslims, reacted, as always, with great violence. Torture was commonplace and entire villages and families were harshly punished and forced to relocate if they were suspected of sympathy for the FLN, with more than two million Algerians evicted from their homes.

Independence Day is still celebrated in AlgeriaPhoto: Public domain

Independence Day is still celebrated in AlgeriaPhoto: Public domain

In 1958, the colons appealed to De Gaulle for even tougher measures and this seemed to be successful. In 1959, France had Algeria under military control, but in France itself support for the struggle in Algeria fell somewhat, and several other colonies in Africa were on their way to independence. As a result, the colons gradually got the idea that Algeria was also on the way to independence and now saw their previous hero De Gaulle as a traitor. In a last attempt to turn the tide, De Gaulle faced two coups and the terrorist Organization de l'Armée Secrète (OAS) caused a lot of unrest with a number of attacks. But the genie was definitely out of the bottle, and in May 1961 negotiations were held between the French government and the FLN. The first result was a ceasefire from 19 March 1962 and a referendum among the Algerians with a predictable outcome: six million Algerians for independence, only 16,000 against. There was now no going back. De Gaulle proclaimed independence on July 3, which became official on September 25, 1962. Immediately a great exodus of French colonists began. The sad result of the war was about 1 million Algerian dead, 18,000 French soldiers killed and 10,000 dead Europeans from other countries.

Algeria independent

Ahmed ben Bella, one of the leaders of the Algerian uprising who had represented Algeria mainly abroad during the war of independence, became the first president of the independent Republic of Algeria and stood for a socialist Arab-Islamic state. Despite the euphoria about independence, old feuds and rivalries soon flared up again and years of war left the country in organizational chaos. Ben Bella came under severe pressure and was deposed as early as 1965 by the Secretary of Defense and FLN Commander, Colonel Houari Boumédienne.

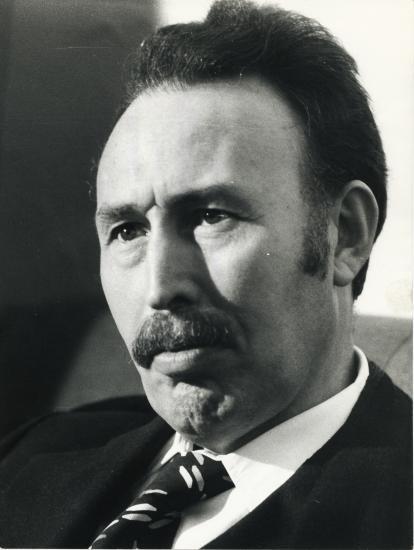

Boumédienne immediately dissolved parliament, suspended the constitution and installed a military council, headed by himself. Ben Bella was exiled, lived on in Switzerland, and did not return until 1990 to lead his party, the Mouvement pour la démocratie en Algérie (MDA). Boumédienne was a cautious and above all pragmatic man, who focused mainly on improving the economic situation of the country. That economy had suffered enormously from the departure of, in particular, many skilled European administrators and technicians. Another major problem was the very high unemployment rate, which meant that many Algerians took refuge in France for a job. Politically almost nothing changed under Boumédienne, the FLN was the only political party. A new constitution was not introduced until 1976. Algeria officially became a party state and Boumédienne president. Algeria's economic situation was eventually saved after the discovery and exploitation of oil and gas fields in southern Algeria, although the large amount of money that was made in doing so did not really end up by the common man.

Houari Boumédienne (1932-1978)Photo: Public domain

Houari Boumédienne (1932-1978)Photo: Public domain

Colonel Boumédienne died in December 1978 and Colonel Chadli Bendjedid was internally elected by the FLN as Algeria's third president. During the Bendjedid reign, which lasted twelve years until 1992, social tensions increased further. Berber students flocked to the ongoing Arabization of government and education. The government made some small pledges to the students, but this sparked furious protests from conservative, straightforward Islamists, who took to the streets to express their displeasure. The police intervened hard, but on the other hand, new mosques were opened and the rights of women were further limited as a remedy. The measures that Bendjedid took to improve the sad state of the economy were also viewed with great suspicion by the old FLN mastodons. The bastion of socialist economic control, a central planning authority, was disbanded and companies and banks were given much more freedom to do business. In 1988, massive strikes resulted in riots in Algiers, and subsequently in cities such as Annaba, Blida and Oran. The violence in the 'October riots' or 'Black October' claimed the lives of about five hundred people. However, the government stood its ground and liberalized society from 1989 onwards. There was more freedom of the press and the political system was also shaken up by the constitutionally permitting political parties other than the FLN. Abassi Madani and Ali Belhadj founded the Front Islamique du Salut (FIS), or Islamic Rescue Front, in 1989, which quickly gained popularity and started winning local elections.

On December 26, 1991, the first free parliamentary elections were held in which several political parties were allowed to participate. The FIS caused a landslide by winning 188 of the 231 parliament seats to be won, the FLN only won 15, even ten less than the Front des Forces Socialistes (FFS), a Berber party with a lot of support in the Kabyli region. However, this went way too far and the army intervened hard. Parliament was dissolved in early 1992, Bendjedid was forced to resign, the second round of the elections was canceled, a state of emergency was declared in February 1992, and the FIS was banned. FIS leaders Madani and Belhadj were arrested and other leaders fled abroad.

Third President of Algeria: Chadli BendjedidPhoto: Public domain

Third President of Algeria: Chadli BendjedidPhoto: Public domain

Bendjedid was initially replaced by a five-person Haut Conseil d'Etat (HCE) headed by President Mohammes Boudiaf. However, Boudiaf was murdered after six months under very suspicious circumstances by a 'lone wolf' who allegedly had religious motives, but it was more likely that Boudiaf had fallen victim to his efforts to eradicate institutionalized corruption in his country. to deal with. Boudiaf was succeeded on July 2, 1992 by FLN hardliner Ali Kafi (1928-2013), who in turn was replaced on January 31, 1994 by a former general, Liamine Zéroual, who took office as Algeria's ninth president in a period that Algeria was on the brink of civil war.

The civil war, already referred to as the 'second liberation war' by militants, had already claimed the lives of more than 3000 people in April 1994, including quite a few foreigners. The guerrillas, united in groups such as Groupes Islamiques Armés (GIA) and the Mouvement Islamique Armé(MIA), mainly targeted police officers, mayors, judges and Francophile intellectuals. The government responded to the violence of these groups with massive arrests of suspects and the setting up of paramilitary death squads to retaliate against guerrilla activities. President Zéroual was unable to reduce the violence, however, as a GIA-set bomb exploded in the Paris metro in July 1995 and an Air France plane was hijacked in Algiers in December of that year. Constitutional reforms were promised in November 1996, but the situation worsened. More than 300 people were murdered in the first two weeks of Ramadan, often through ritual massacres.

Liamine Zéroual, ninth president of AlgeriaPhoto: Reda Kerboush CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Liamine Zéroual, ninth president of AlgeriaPhoto: Reda Kerboush CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

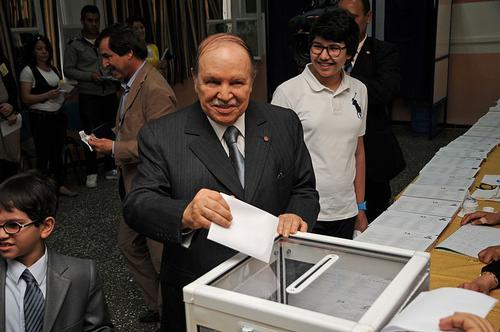

In 1998, President Zéroual was forced to resign and the military appealed to former Foreign Minister Abdelaziz Bouteflika to become president. Bouteflika 'won' the 1999 elections, there were seven candidates who, however, withdrew on election day, and he announced a policy of reconciliation and nationall unit. A number of Islamist fighters were even offered amnesty if they surrender their weapons and he corrected the image that in the civil war so far 'only' 26,000 would have been killed according to official government position. Bouteflika admitted that there had been at least 100,000, and in addition, for the first time ever by the government, he admitted that the 1992 electoral cancellation had been an 'act of violence' against the FIS.

In June 1999, Bouteflika received a guarantee from the leader of the FIS that the guerrilla branch, the GIA, would no longer turn against the government, and asked other terrorist groups to do the same. A split is beginning to emerge in the GIA, with some members looking to participate in the peace process. These signs of optimism are reinforced when a number of Muslim terrorists want to grant amnesty. In July 1999, on the 37th anniversary of an independent Algeria, some 5,000 prisoners were released.

In a September 1999 referendum, Bouteflika received strong support for his plans to end the civil war: Approximately 85% of Algerians entitled to vote took part in the referendum and 98% voted in favor of the president's plans.

In 2004, President Bouteflika was re-elected for a second term and continued his program of national reconciliation, reform of the national economy and opening abroad. That second term was only possible due to a change in the constitution regarding the maximum number of terms of office for a president.

Even in his second term as president, Algeria continued to suffer from high unemployment, a housing shortage, electricity and water problems and an inefficient and corrupt civil service.

In 2006, the Groupe Salafite pour la Prédiction et le Combat (GSPC), an offshoot of the GIA, joined Al-Qaeda and changed to January 25, 2007 its name in Al-Qaïda au Maghreb Islamique (QMI), which is characterized as a terrorist organization in the United States, Canada and Great Britain, among others.

In 2007 there are many QMI bombings and kidnappings in Algeria targeting the government and Western individuals and interests in Algeria.

In June 2008, President Bouteflika appointed Ahmed Ouyahia as new prime minister. Ouyahia became Prime Minister of Algeria for the third time, from December 31, 1995 to December 15, 1998, from May 5, 2003 to May 24, 2006, and from June 23, 2008 to September 3, 2012.

In November 2008 Parliament passed a constitutional amendment paving the way for a third term for Boutaflika, who clearly won the presidential election in April 2009 and could begin his third term as president.

Ahmed Ouyahia, Prime Minister of AlgeriaPhoto: Magharebia CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Ahmed Ouyahia, Prime Minister of AlgeriaPhoto: Magharebia CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

During the 2010-2012 period of the Arab Spring, protests continued throughout Algeria from December 28, 2010, inspired by similar protests in the Middle East and the rest of North Africa. Causes of these demonstrations included unemployment, housing shortages, increasing food prices, corrupt government, restrictions on freedom of expression and poor living conditions. Local protests were commonplace long before 2010, but the wave of demonstrations and riots, fueled by a sudden rise in food prices, were unprecedented so far. The government quickly intervened by cutting food prices, but the genie was already out of the bottle and the situation escalated with a number of self-immolations for government buildings. Despite the declaration of a state of emergency, opposition parties, trade unions and human rights organizations began to hold weekly demonstrations without the permission of the government. The government suppressed these demonstrations as much as possible, but lifted the state of emergency. Protests by unemployed young people against high youth unemployment, oppression and infrastructure problems were still scattered across the country on an almost daily basis inmajor cities.

In 2011, in response to the Arab Spring in Tunisia and Egypt, for example, the Algerian government proposed political reforms, such as ending the 19-year state of emergency and increasing the number of women who worked for the government. In October 2011, the second metro in Africa went into operation in Algiers.

On 3 September 2012, Abdelmalek Sellal was appointed Prime Minister by President Bouteflika to succeed Ahmed Ouyahia. Parliamentary elections in May 2012 and provincial elections in November 2012 were won by the FLN, while Islamist opposition parties performed poorly. foreign workers. An Algerian security guard and 38 foreigners were killed before elite forces of the Algerian army recaptured the complex.

In April 2013, Bouteflika was nursed in France after suffering a stroke. Political protests from the population were limited in 2013, except for some violent socio-economic demonstrations by various groups.

In July 2014, Bouteflika returned to Algeria, where he ran for another presidential election in 2014 and was re-elected for a fourth term in April. He received help from Sellal, who briefly stepped down as prime minister and acted as campaign leader for Bouteflika during the election period. His replacement was Youcef Yousfi, on April 28, 2014 Sellal resumed his position as Prime Minister. With a turnout of 51.7%, Bouteflika obtained a large majority with 81.53% of the votes. Its main competitor Ali Benflis received only 12.8% of the vote.

Abdelmalek Sella, Prime Minister of AlgeriaPhoto: Rama CC 2.0 France no changes made

Abdelmalek Sella, Prime Minister of AlgeriaPhoto: Rama CC 2.0 France no changes made

In September 2014, the kidnapped French tourist Hervé Gourdel was beheaded by Muslim extremists from the Jund al-Khilafa (Soldiers of the Caliphate) group. Gourdel was kidnapped in the Djurdjura Mountains, southeast of the capital, Algiers. In February 2015, it was announced that there are two Algerian universities in the new ranking of the best universities in the Arab world. The Djillali Liabes University of Algiers was ranked 12th, the University of Bejaia 27th. Less attractive was that in the same month it was announced that Algeria was one of the twenty countries that dumped the most plastic waste in the sea. Algeria was ranked 13th in the top marine pollutants ranking by the University of Georgia and the Massachusetts Sea Education Association. In September 2015, President Bouteflika fired Mohammed Mediene, who has been the head of the security service for 25 years. In February 2016, parliament will implement reforms, Berbers will be given official status and the president may only be elected for 2 terms. In May 2017, the government will retain its majority after parliamentary elections. In January 2018, the traditional New Year of the Berbers will become a national holiday. In April 2019, Bouteflika will resign after continuing street protests. Abelkader Bensalah speaker of parliament will become interim president and succeeded in December 2019 by Terboune. Abdelaziz Djerad becomes the new Prime Minister. He will be succeeded by Ayman Benabderrahmane on 7 July 2021.

Sources

Agada, Birgit / Algerien : Kultur und Natur zwischen Mittelmeer und Sahara

Trescher

BBC - Country Profiles

Beker, Michel / Algerije

KIT Publishers/Oxfam Novib

CIA - World Factbook

Elmar Landeninformatie

Ham, Anthony / Algeria

Lonely Planet

Kagda, Falaq / Algeria

Marshall Cavendish

Oakes, Jonathan / Algeria

Bradt Travel Guides

Copyright: Team The World of Info