VENEZUELA

History

History

Cities in VENEZUELA

| Caracas |

Popular destinations VENEZUELA

| Isla margarita |

History

Pre-Columbian Period

Pre-Columbian petroglyph in VenezuelaPhoto: Arnaldo Noguera Sifontes CC 4.0 International no changes made

Pre-Columbian petroglyph in VenezuelaPhoto: Arnaldo Noguera Sifontes CC 4.0 International no changes made

Around 14,000 years before Chr. the first people arrived in what is now Venezuela. Primitive nomadic peoples from that time populated the Venezuelan territory. However, Venezuela has never had an Indian people in its territory like the Aztecs and the Maya in Central America or the Incas in the neighboring Andes mountains. One of the reasons for this could be climatic conditions. In any case, they were not large political units as with the aforementioned peoples, because nowhere in the warm lowland forests of South and Central America has a high degree of organization been established. There were only small tribes, each with their own culture and language. Some were semi-nomadic, others were farmers. The size of the then indigenous population was small. And because nothing has been written down, very little is known about the first inhabitants of Venezuela.

Columbus discovers America and Spanish rule

Christopher Columbus, VenezuelaPhoto:Public domain

Christopher Columbus, VenezuelaPhoto:Public domain

The year 1498 is of course a turning point in history for the entire American continent. In that year Columbus landed on his third voyage on the eastern tip of Venezuela, the Paria peninsula. The outer mouth of the Orinoco and the island of Margarita were also explored. In 1499 Alonso de Ojeda and Amerigo Vespucci sailed off the current city of Maracaibo. Because of the stilt houses of the Indians, the region was called Venezuela, which means “Little Venice. In the year 1500, the first Spanish settlement in Latin America is established on the island of Cubagua. In 1508, Ojeda became the first governor of the area, but the Spanish failed to establish a permanent colony. The mission attempt by the Franciscan monks also failed for the time being.

It was not until 1521 that they succeeded in founding the first city on the South American mainland, Cumaná. Groups of Negro slaves were introduced on a modest scale, some of which can still be found on the north coast of Venezuela. In total, about 120,000 slaves ended up in Venezuela. The Indians were also transported as slaves to Cuba, Cubagua or Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic). In 1527, Venezuela is leased by Charles V to the German banking house Welser. In search of gold, they left a trail of misery among the Indian population. The Spaniards also continued to advance the Orinoco in search of gold. But they too had little success. In 1546 the lease with the Germans was terminated and the whole of western Venezuela was conquered by the Spaniards. More and more settlements were founded, many of which still exist today.

Diego de Losado founds Caracas, the capital of VenezuelaPhoto: Public domain

Diego de Losado founds Caracas, the capital of VenezuelaPhoto: Public domain

Caracas was founded by Diego de Losada around 1577 and the city was soon declared the capital of western Venezuela. In 1580 the population was hit by a smallpox epidemic and many Indians died of this unknown disease. In 1595, the English came onto the scene and Caracas was destroyed by Sir Francis Drake, the famous English pirate and explorer. The persistent rumors about gold treasures attract not only Spaniards and English, but also Portuguese, French and Dutch. Moreover, the political situation in Europe at that time also had an influence on the developments in South America. For example, the Dutch had a fort on the edge of the Corantijn with tobacco plantations. However, this fort was destroyed by the Spanish governor in 1613. In 1621, the Dutch returned under the leadership of the West India Company and inflicted some sensitive defeats on the Spaniards. It is, among other things, the time of the conquest of the Spanish treasure fleet by Piet Hein near Cuba in 1628.

In 1681, the “Indies Act” came into effect which revised all of the legislation governing the American colonies on the orders of Philip II. In order to tackle piracy and smuggling, the “Caracas Company” was founded in 1728, which was given full monopoly over trade and the economic development of the province of Caracas. The Spanish possessions in South America at that time consisted of a number of separate provinces ruled from Santo Domingo, currently the capital of the Dominican Republic. This did not change definitively until 1777 when six provinces, including Margarita, Caracas, Guayana and Trinidad, were merged and Venezuela was given its own administration under the leadership of a Spanish soldier. Venezuela had about 800,000 inhabitants at that time. Trinidad falls after some time and falls into English hands.

Simón Bolívar and the Struggle for Independence

In 1806, Francisco de Miranda, influenced by the French Revolution, assembled an army of American volunteers who tried to make Venezuela independent. This attempt failed, but on April 19, 1810, a group of the wealthy Venezuelan elite seized power by establishing a Supreme Junta that convened the "First Congress." The First Congress met for the first time on March 2, 1811, and on July 5, 1811, Venezuela became the first American colony to declare independence and the so-called "First Republic" was established. The seven provinces of Mérida, Trujillo, Caracas, Cumaná, Barcelona, Margarita and Barinas then together form "La Confederacíon Americana de Venezuela". Francisco de Miranda is at that time the commander in chief of the revolutionary armed forces.

Statue of Simon Bolivar in Ciudad Bolívar, VenezuelaPhoto:Guillermo Ramos Flamerich CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Statue of Simon Bolivar in Ciudad Bolívar, VenezuelaPhoto:Guillermo Ramos Flamerich CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Under him, the later president Simón Bolívar serves. In 1812 the Spanish captain-general destroyed Monteverde via the royalist-minded south, the northern republican provinces. De Miranda is accused of treason by Bolívar and extradited to the Spanish. In December 1812, Bolívar embarks on a campaign against the supporters of the Spanish king. He strikes victory after victory and triumphantly enters Caracas in early August. Liberation is also launched from the east and the royalist troops are eventually defeated in the Battle of Bárbula and they withdraw to the fortress of Puerto Cabello. Bolívar is proclaimed liberator and commander in chief of the revolutionary armed forces.

However, the royalist forces led by their commander Boves fight back and eventually advance towards Caracas. The entire population fled with Bolívar to the east, but many are killed or killed by Boves' troops along the way. The Spaniards wanted to arrest Bolívar, but he had already left for Cartagena in Colombia where he is appointed commander-in-chief, conquers Bogotá and forms a government. Spain meanwhile sent a large army to Venezuela while the revolutionaries received military help from the British who mainly acted for economic reasons. Bolívar received more and more help, also from neighboring countries.

Margarita Island was liberated in 1816 and Guayana a year later. In 1819 Bolívar liberated Colombia and proclaimed the Greater Colombian Empire, which consisted of the present-day states of Venezuela, Panama, Ecuador and Colombia. He himself became the first president. The Spaniards, of course, fiercely resisted, but suffered a decisive defeat at the Battle of Carabobo on June 24, 1821. The Spaniards were also defeated in other countries in South America and after the lost Battle of Ayacucho in Peru, 300 years of Spanish colonialism in South America came to an end.

Venezuela is finally released by the Spanish in 1823. Independence, however, turned into a disillusionment as the individual countries of Greater Colombia quickly let self-interest prevail again. Corruption was rampant, slavery was not abolished as agreed and the fight for power broke out on all fronts. Not even Bolívar could keep the Greater Colombian Empire together and he died a disappointed man in 1830, but is still a legend in South America and is still called the “father of the country”.

Era of the dictators

From 1830, Venezuela went its own way and the era of the dictators started. The first was General Paéz who also became the first president of the Republic of Venezuela. During the reign of the second president, Monagas, slavery was officially abolished in 1854 and relations with Spain were restored. Due to internal infighting and political conflicts, a civil war (Federal War) broke out in 1858, which lasted until 1864. In that year the Federal Republic of Venezuela was proclaimed. Britain took advantage of this by adding a piece of Venezuela to British Guiana, something that is still disputed by Venezuela and is known on all maps in Venezuela as “Zona en adacíon”.

Headstone Antonio Guzmán Blanco, VenezuelaPhoto: Alex Coiro CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Headstone Antonio Guzmán Blanco, VenezuelaPhoto: Alex Coiro CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

The dictatorship of the infamous Antonío Guzmán Blanco (1870-1888) initially seemed to benefit the people. He separated state and church and managed to reduce the political influence of the powerful and wealthy families. However, it turned out to be an illusion because he was mainly out to fill his own cash and did not tolerate any opposition, for example. After the Guzmán Blanco period, the dictators succeeded each other in rapid succession. Cipriano Castro lasted the longest (1898-1908) and Juan Vincente Gómez would become the cruelest in Venezuelan history. More than 30,000 Venezuelans went to prison and at least as many fled abroad.

Despite the antipathy to the United States throughout South America, Gómez established relations with the Americans entirely out of self-interest after the discovery of oil. Investors poured in and the United States became the most important trading partner of Venezuela or Gómez and henchmen. In 1928 there were demonstrations by students (Generation 28) and workers against Gómez and his pro-American politics. Although the protests were crushed, these were the first steps towards political democracy.

After Gómez's death in 1935, there was even room for political parties. The Social Democratic Party would eventually join the junta in 1945 and a transitional phase between military dictatorship and democracy emerged. In 1945, the citizen and best-known Venezuelan writer Rómulo Gallegos was appointed president of the junta. He introduced universal suffrage but failed to get the military completely on the second plane.

From dictatorship to democracy

On the contrary, in 1947 there was another coup led by General Jiménez that would eventually become Venezuela's last dictator to date. His reign lasted until 1957. He was expelled amid growing popular protest and with the help of the army. From 1958, Venezuela was the first country in South America to change from a dictatorship to a fairly stable democratic state. After the first democratic elections in 1959, a cabinet of national unity was formed under the leadership of President Rómulo Betancourt.

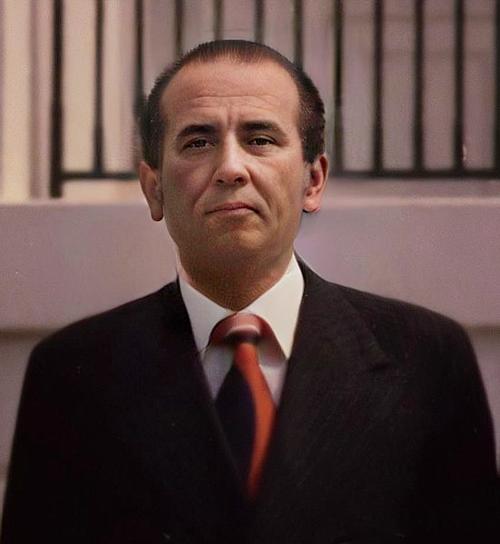

In 1961, the democratic system was constituted and Venezuela became a federal republic again. In 1960 Venezuela was one of the founders of OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries). However, only a small part of the population benefited from the tremendous oil revenues. The revolutionary ideas from Fidel Castro's Cuba soon spread to Venezuela, but due to the large growth in employment, especially in the metal sector, support from the population was not forthcoming. There has therefore never been a possible revolution in Venezuela. Venezuela began golden times under President Carlos Andrés Pérez (1973-1978). He turned the oil and steel industry into state-owned companies, leaving all revenues in Venezuela. With that money, the country was modernized, infrastructural facilities realized, the industrial sector expanded and agriculture got new impulses. The middle class of the population also benefited from these developments and Pérez was the new hero. However, it turned out that he had accumulated a billion-dollar debt and Venezuela was actually practically bankrupt.

His second term in office began in 1988 and was forced by the World Bank and the IMF to cut spending and restructure, particularly in the massive government apparatus. Business was privatized again, tariffs for water, petrol and foodstuffs, among other things, shot up. The people did not take it, resulting in looting and fighting with the police in 1989, resulting in hundreds of deaths and injuries, arrests and torture. It even got to the point where two coups were staged in 1992, but both failed.

Carlos Andrés Pérez, VenezuelaPhoto: Public domain

Carlos Andrés Pérez, VenezuelaPhoto: Public domain

In March 1993, President Pérez was charged with corruption and expelled for three months and placed under house arrest. This house arrest was lifted in 1996. In the presidential election at the end of 1993, an independent candidate, Rafael Caldera, won the most votes for the first time in history. He kept the army in check and had no choice but to continue the austerity program that had been started. In 1994, Venezuela entered a banking crisis and the Venezuelan government took over 18 of 40 private banks. Rising exports caused the economy to recover somewhat in 1995. Due to the increase in crime and violence, many civilian protests followed in 1996. In 1996, for the first time in 20 years, foreign companies were allowed to compete again for exploitation rights to extract oil and a new economic recovery program was announced by President Caldera. As a result, there was again a slightly growing economy.

In July 1997, a powerful earthquake (6.7 on the Richter scale) in central and eastern Venezuela killed at least 59 people and injured more than 300. The cities of Cumana and Cariaco were hit the hardest. In August 1997, riots at El Dorado Prison in Bolivar State, Venezuelan, killed 42 inmates and injured 22. The year 1997 was again marked by much social unrest and riots with the riot police. In March 1998, five major oil-producing countries, including Venezuela, decided to drastically cut their oil production. The countries hoped to bring the oil price, which had reached an all-time low, back to normal through production restrictions. As of July 1, Venezuela started to deliver 125,000 barrels less daily. The agreements applied for the remainder of 1998.

Hugo Chavez at the military academy, VenezuelaPhoto: Government of Venezuela CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Hugo Chavez at the military academy, VenezuelaPhoto: Government of Venezuela CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In 1998, the presidential elections were surprisingly won by Hugo Chávez Frias (44 years old) who had launched another failed coup d'état against the Pérez government in 1992 (in 1994 he received amnesty after two years in prison). He received a lot of votes from the slums because he had made many promises, especially to the poor. Chavez received almost 60% of the vote, his opponent, the 62-year-old entrepreneur Henrique Salas, about 35%. In January 1999, Chavez was welcomed back to the United States (so far he was never granted a visa because of the failed 1992 coup and he was suspected of dictatorial tendencies). On February 2, 1999, Chavez was sworn in as president of Venezuela. A week after being sworn in, Chavez declared a "social emergency". He wanted parliament to give him powers of attorney to reorganize government spending in order to reduce the funding deficit. Furthermore, hhe reformed the tax system and announced that the military would assist in farm work, road repair and health care, the "Bolivar 2000" plan. He also wanted to remediate the corrupt political system and combat poverty. His plan to dissolve parliament was most criticized. In early February, he issued a decree requiring a legislative assembly to write a new constitution. The population should be allowed to comment on the desirability of this. In the city of Cumana, some 500 kilometers east of the capital, Caracas, serious student riots broke out around March 1 and lasted for three days.

At the end of April, the Venezuelan people voted in a referendum for amendment of the 1961 constitution. In doing so, the population massively supported the "peaceful revolution" announced by President Chavez. Approx. 88% of voters voted in favor of forming an "Asamblea Nacional Constituyente", an assembly to revise the constitution. 82% also agreed with the conditions set by Chavez for the appointment of that assembly. Opponents of Chavez feared that through the new constitution he wanted to seize executive, legislative and judicial powers. This was confirmed one more time after Chavez's unconstitutional promotion of 34 soldiers. After criticizing this, he openly threatened to dissolve parliament: "I am at war with you, there is no place for both of us in this country. Your days are numbered".

At the end of July, the left-nationalist government of Chavez won an overwhelming victory in the election of a constituent assembly, which was to draft a new constitution within six months. 119 of the 131 seats were occupied by Chavez supporters, giving him the opportunity to break the power of the traditional parties.

A few weeks later, the Constituent Assembly took all power and declared a state of emergency before Venezuelan courts, Congress and other institutions. This state of emergency enabled the Assembly to intervene in public institutions as it saw fit, as required by the special Constituent Assembly to tackle corruption in those institutions. In protest, the president of the Venezuelan Supreme Court, Cecilia Sosa, resigned on August 24.

At the end of August, parliament was deprived of its last rights by decree, after a week earlier the rights in the area of legislation had been severely curtailed. At the time, the Constituent Assembly was, in fact, the highest authority in Venezuela. In mid-September, Congress was allowed to resume its usual duties with the exception of exercising legislative power.

In early November, the Constituent Assembly agreed to the controversial extension of Chavez's term, as well as lifted the blockades that stood in the way of the president's re-election. In theory, this amendment allowed him to remain in power until 2012.

On December 15, the new constitution was passed with 71% of the votes. In this, citizens get more rights and more influence. Referendums make it possible, for example, to send bad representatives of the people home. furthermore, Chavez got a much stronger grip on the economy and the position of the president and the army was strengthened and the Senate was abolished. From now on, the president could also dissolve parliament if he deemed it necessary.

Shortly after the referendum, Venezuela was hit by a natural disaster of unprecedented magnitude. Floods and mud avalanches caused at least 20,000 deaths and 140,000 people were made homeless. The military was cast in a bad light after reports of beatings, looting and even executions. However, there was no hard evidence for this.

21st century

At the beginning of January 2000, the minister of infrastructure, Julio Montes, resigned out of dissatisfaction with the militarization of the government. Chavez then announced to replace more members of his cabinet with military personnel. Elections for the president, Congress, governors and local councils, scheduled for the end of May, were canceled because the computer system that would count the votes turned out to be unreliable. At the end of July, Chavez was elected president for six years, but was unable to get a two-thirds majority in parliament. Chavez himself received about 60% of the vote, his opponent Francisco Arias Cardenas got about 38% of the vote. In August, Chavez paid a controversial visit to Iraq, where he met Saddam Hussein. It was the first visit by a foreign head of state to Iraq since the 1991 Gulf War. The United States in particular reacted furiously, but Chavez did not care either.

Hugo Chavez, VenezuelaPhoto: Dilma Roussef CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Hugo Chavez, VenezuelaPhoto: Dilma Roussef CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

In mid-October, about 35,000 workers in the Venezuelan oil industry ended their strike. The strike had broken out a few days earlier after the government refused to give a wage increase of nearly $ 10 a day. The strikers reached an agreement with the national petroleum company PDVSA. In late October and early November, Cuban President Fidel Castro paid a visit to Venezuela with the intention of buying oil at a bargain price. They succeeded and it was agreed that Venezuela would deliver 53,000 barrels of crude oil to Cuba daily in exchange for Cuban goods and medical services. The Venezuelan opposition was furious because about 80% of its own population lived well below the poverty line. On November 7, the National Assembly gave President Chavez an unprecedented position of power by allowing him to enact laws on oil and banking by decree for one year. On November 13, 63-year-old oil minister, Ali Rodriguez Araque, was elected Secretary General of OPEC. In early December, Chavez was heading for a victory in a referendum on the formation of new unions. Many voters said "yes" to plans to overthrow traditional leaders. According to the opposition, Chavez was expanding his dictatorial power even further.

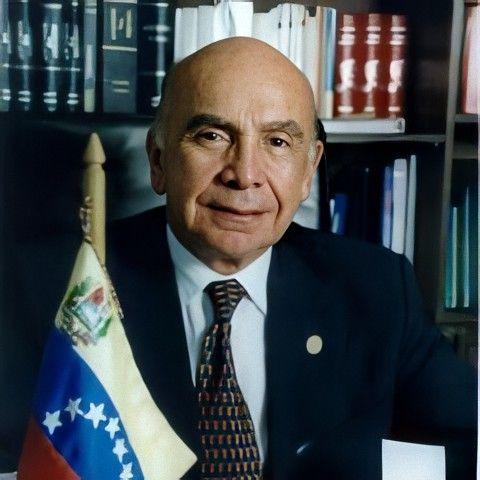

Pedro Carmona, VenezuelaPhoto: Zcriptz CC 4.0 International no changes made

Pedro Carmona, VenezuelaPhoto: Zcriptz CC 4.0 International no changes made

On April 11, 2002, a mass demonstration took place in Caracas demanding Chávez's resignation. Fighting broke out and killed 15 people, and the Venezuelan president was held responsible by the media and opposition. Chávez was then forced to resign by a group of rebel soldiers and Pedro Carmona was appointed interim president. Although even the media talked about the president's “resignation”, a coup d'etat did take place on April 11.

That became clear when Carmona immediately unleashed a real manhunt on Chávez supporters and dissolved parliament. As a protest against this, the often poor Chavez sympathizers took to the streets en masse to demand the resignation of Carmona. Part of the army sided with Chávez and that was the signal for Carmona to flee. On the night of April 13, Chávez returned to the presidential palace.

The United States, declared opponent of Chávez, was obviously not happy with his return. They still feared that Chávez, a friend of Cuban leader Fidel Castro, would one day cut oil supplies to the United States.

A week after the failed coup d'état, all coup plotters were free again, raising the question of whether there had been a coup. In any case, it was very remarkable that the commander in chief of the army and one of the coup plotters, Lucas Rincon, were reappointed. Pedro Carmona denied before a parliamentary inquiry committee that he would have prepared the coup together with the army. He stated that he had been asked by the military to fill the 'power vacuum'.

In late April 2002, three Venezuelan military leaders filed for political asylum in the United States. They had already fled to the Bolivian embassy after the failed coup. Carmona was eventually allowed to leave for neighboring Colombia, where he was granted political asylum.

The month of May was also the scene of demonstrations, in which tens of thousands of Venezuelans took to the streets. In July, former United States President Jimmy Carter made an unsuccessful attempt to mediate between President Chávez and the Venezuelan opposition demanding the president's resignation.

In early August, four senior military officers were acquitted for lack of evidence who had taken part in the brief coup d'état against President Chávez. Anger at this statement prompted further demonstrations by Chávez supporters, with further deaths and injuries. Carlos Andrés Pérez, the former president, openly advocated replacing Chávez with a military junta. He predicted a coup that would again cause a lot of blood.

Since the Supreme Court's dubious ruling on the coup attempt, Venezuela has been split between supporters of Chávez, who believed he stood up for the rights of the poor, and opposition members, who felt he was actually driving a wedge between the different classes.

On October 11, about one million people in Venezuela demonstrated against President Chávez's nationalist government, calling for new elections. Protesters from different cities marched to the capital, Caracas. The opposition was supported by employers, trade unions, all traditional political parties, most media, churches and student organizations. The largest union threatened a general strike and gave the president a few days to step down. Several days later, hundreds of thousands of supporters of the Venezuelan president marched through the streets of Caracas in response to the opposition demonstration. Chávez had called them to this.

At the end of October, a massive general strike shut down part of Venezuela. Factories and shops were closed, domestic flights were canceled. Rumors even circulated about a possible coup, and shootings with the police took place in several places. In the center, the army had parked tanks in front of the presidential palace.

A day later, fourteen senior army officers on Venezuelan television called the population to civil disobedience. The fourteen felt that the president no longer represented the voice of the people. Some of them were also involved in the April coup, and have not held active positions since then. In the end nothing happened.

In early November, supporters of Chávez clashed with opposition members. At least sixteen people were injured. The president's supporters tried to prevent the opposition from offering two million signatures to parliament. Trade unions and opposition members wanted the signing campaign to ensure that a referendum on early elections would be held on December 4. Several days later, Chávez asked the Supreme Court to annul parts of the Venezuelan electoral law, which would stop the electoral council. can operate on a legal basis. The opposition then threatened a general strike.

In mid-November, the army of Venezuela took over the duties of the police in the capital Caracas. The takeover by the army would be intended to restore peace to the police. "The police have fallen into anarchism," Chávez said. Part of the metropolitan police has been on strike since October against Mayor Alfredo Peña, a staunch opponent of Chávez. He also accused Chávez of the president's own police strike in order to push a new, loyal government commissioner down the throat of the capital.

At the end of November, the Supreme Court ruled that a previously announced referendum on the early presidential election on February 2, 2003 should not go ahead. A general strike against Chávez's rule followed on December 5. This strike brought the Venezuelan economy, and especially the oil sector, to a standstill. In response, Chávez ordered the army to intervene to secure oil supplies abroad. At that point, all-out civil war didn't seem far away.

When the strikes had not ended after a week, Chávez threatened to declare a state of emergency. On December 9 it was announced that the Venezuelan government no longer ruled out elections as a solution to the resulting crisis. This announcement came after negotiations between Chávez, the opposition and the Secretary General of the Organization of American States (OAS), César Gaviria. It was unclear whether Chávez actually wanted to cooperate.

Meanwhile, the strikes entered their second week, and Chávez threatened to declare a state of emergency in the country. All oil facilities in the country were occupied by the military to avoid sabotage. Characteristic of the hopeless situation was the cessation of the activities of the Supreme Court for 'political intimidation'.

On December 13, the United States urged Chávez to hold early elections, and on December 16 hundreds of thousands again marched in the capital, Caracas.

A day later, opposition leaders called on the population to further sharpen actions against the government. Fierce clashes between protesters and riot police resulted. All the cautious approaches and the pressure from the outside had had no effect at all.

On December 19, the Venezuelan court ordered the oil industry workers to return to work. However, most of the strikers ignored the Court's order and continued on strike unabated. The controversial head of state then threatened to dismiss all strikers at the state oil company Petreleos de Venezuela.

On January 3, the police had to intervene violently to prevent protesters from storming a military base near the capital. A crowd of tens of thousands of protesters had gathered in front of the barracks complex to demand the release of a general placed under arrest for mutiny. About 100 officers had joined the strike movement, but most military commanders remained loyal to the head of state.

On January 14, the police of the capital Caracas were disarmed by the Venezuelan army. Chávez accused police of attacking supporters of his regime during demonstrations. On January 17, representatives of the countries of Mexico, United States, Brazil, Chile, Spain and Portugal established a 'Group of Friends of Venezuela'. They wanted to try to find a solution to the political crisis in the country.

In early February, the general strike was ended by Chávez's divided opponents. The oil sector was still partly on hold, but it was clear that Chávez had survived the 64-day crisis. The attempt to force Chávez to resign through strikes had been totally unsuccessful. A few weeks later, the Venezuelan government and the opposition reached an agreement against violence, peace and democracy. However, this agreement was again called into question when Carlos Fernández, leader of the opposition and chairman of the employers' association Fedecamaras, was arrested; however, it remained quiet in the country.

At the end of February, Venezuela was startled by attacks on the Spanish embassy and the Colombian consulate in the capital Caracas. Chávez supporters were identified as the perpetrators because Spain, Colombia and other countries had tried to mediate between the president and the opposition.

In mid-April, the Venezuelan government and opposition reached an agreement to hold a referendum on the premature end of Hugo Chávez's presidency. According to the constitution, the referendum could take place after August 19, halfway through the presidential term. However, this did not happen and in mid-September the Venezuelan Electoral Council even rejected the petition calling for a referendum on Chávez's position due to procedural errors.

In early December, more than 3.6 million Venezuelans signed a petition calling for a referendum to end President Chávez's tenure. That number was significantly higher than the 2.4 million signatures required by the constitution to hold a plebiscite.

March 7, 2004: Hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets in the Venezuelan capital of Caracas to protest against President Hugo Chavez. In the biggest rally this year, they demanded a referendum on the deposition of the left-nationalist Chávez and expressed displeasure at the way police and military "brutally repressed" previous demonstrations.

Since the end of February, clashes between opposition members, supporters of the government and police and military have killed at least nine people. According to the opposition, authorities arrested about 400 protesters and injured 1,650 people in the violence. In August 2004, President Chávez was challenged again when the Venezuelan people, in a referendum proposed by the opposition, were able to decide whether to finish his term in office.

The outcome of the referendum indicated that 58% of the Venezuelan population was in favor of Chávez's remaining president. The OAS and the Carter Center, which acted as independent observers to the referendum, confirmed that no evidence of fraud or harassment had been found, even though suspicions persisted. The opposition, made up of the radical anti-chávistas of the Democratic Bloc and the more moderate mainstream parties, has since divided. The ad hoc coalition "Coordinadora Democrática" has disintegrated and in fact there is no longer any significant opposition, except in a few states and municipalities where local parties and personalities are exceptions to the trend. This was evident in the parliamentary elections in December 2005, in which President Chávez's "Movimiento Quinta Repú blica" (MVR) and her coalition partners from the "Bloque de Cambio" secured all 167 seats according to the preliminary results. The opposition parties AD, COPEI and "Primero Justicia", who saw defeat coming, had withdrawn shortly before the elections and called on the people to stay at home. The turnout rate of 25% was a historic low (in 2000 the turnout was 57%). The EU observer mission did not identify any irregularities. She noted that there is no confidence in the electoral system in Venezuela and made a number of recommendations in this area.

President Chávez has interpreted the results of the referendum and subsequent elections as strengthening his revolutionary mandate. A true proliferation of legislation would help to further strengthen the government's grip on society and also to shape the principles of the Bolivarian revolution. In December 2006, President Chávez is elected for a third term. In December 2007, Chávez lost for the first time a referendum calling for more power and an acceleration of the socialist revolution. In 2008, Chávez became explicitly involved in the Colombian conflict with the FARC, and he got a number of hostages released.

Relations with Colombia become tense after a chase by the Colombian army on the FARC on Venezuelan territory. In July 2008 the relationship relaxes again after the liberation of Ingrid Betancourt. President Uribe visits Chávez. In November 2008, the opposition gains slightly in local elections. In February 2009, voters agreed to abolish the number of terms a politician can be re-elected. This could pave the way for Chávez to be re-elected after 2012 as well. At the end of 2009, tensions with Colombia are running high, partly because of an extension of the contract between the US and Colombia on the use of military bases. In March 2010, the central bank announced that the economy had contracted by 5.8% in the last three months of 2009. In September 2010, President Hugo Chávez retained the majority in parliament, but the opposition managed to prevent the party Chávez once again gains a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly. In June 2011, President Chavez begins cancer treatment in Cuba. In October 2012 he won the presidential election for a fourth time. In December 2012, Chavez returned to Cuba for further treatment and appointed Nicolas Maduro as his successor while he was ill. Hugo Chávez dies on March 5, 2013 in the capital Caracas.

Nicolas Maduro, VenezuelaPhoto: Valter Campanato/ABr CC 3.0 Brazil no changes made

Nicolas Maduro, VenezuelaPhoto: Valter Campanato/ABr CC 3.0 Brazil no changes made

In April 2013, Nicolas Maduro is narrowly elected as president. In December 2013, his party strengthened its position in local elections. In February 2014 there have been disturbances in Caracas, the government says the opposition is looking for a coup. In December 2015, the opposition wins congressional elections after 16 years of socialist dominance. In February 2016, President Maduro announced measures to combat the economic crisis, including a monetary devaluation and an increase in gasoline prices. The years 2016 and 2017 are dominated by mass protests against the belead from Maduro. In January 2018, Aruba, Bonaire and Curacao will face an export ban and a sea, air and land blockade of the islands by Venezuela. In januaty 2019 opposition leader Juan Guaidó declares himself interim president, appeals to military to oust President Maduro on the grounds that the 2018 election was rigged. Since then, Guaido has been trying to oust Maduro from power and he is recognized by some 50 countries worldwide as interim president. However, he never succeeded in removing military-backed Maduro from power. In December 2020, Maduro wins the elections boycotted by Guaidó.

Sources

Dydyñski, K. / Venezuela

Lonely Planet

Ferguson, J. / Venezuela : mensen, politiek, economie, cultuur

Novib

Launspach, W. / Reishandboek Venezuela, Margarita

Elmar

Morrison, M. / Venezuela

Chelsea House Publishers

O’Bryan, L. / Venezuela, Isla Margarita

Gottmer

CIA - World Factbook

BBC - Country Profiles

Copyright: Team The World of Info