ANGOLA

History

History

History

Early History

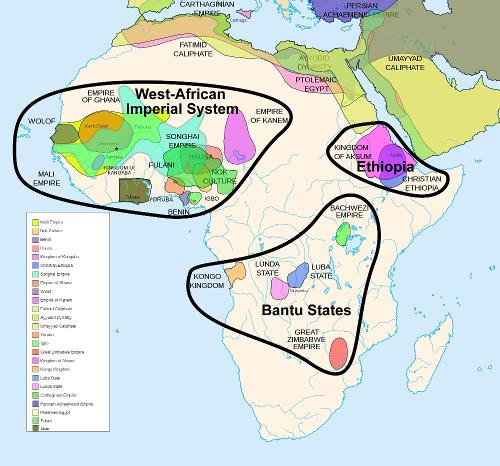

Little is known about the early history of the area now called Angola, although it is thought to have been inhabited by hunter-gatherers since the Lower Paleolithic. In the early 6th century, Bantu-speaking people came from the north who smelt iron and brought agricultural knowledge with them, and in the 10th century separate kingdoms began to form.

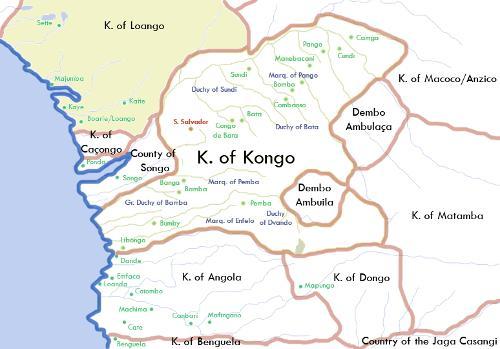

Most important of these kingdoms was the Kingdom of Kongo which expanded in the 13th and 14th centuries to the area from present-day Gabon to the Kwanza River, south of Luanda, and inland to the Cuango River. The Congo kings founded agricultural and fishing colonies at the mouth of the Congo River, divided the territory into smaller provinces, used shells as currency and even levy taxes. By the mid-15th century, the Congo Kingdom was the most powerful of a series of states along the African west coast.

Pre-colonial civilizations in Africa, 500 BC. - 1500 AD.Photo: Jeff Israel CC 3.0 no changes made

Pre-colonial civilizations in Africa, 500 BC. - 1500 AD.Photo: Jeff Israel CC 3.0 no changes made

First Europeans

The first European settlers arrived in 1482 when the Portuguese navigator Diogo Cão moored his caravels at the mouth of the Congo River. The Portuguese initially maintained peaceful relations with the Kongo tribes; the Manikongo (king) converted to Christianity and asked for missionaries and guns in exchange for slaves, ivory and other goods. Other expeditions followed and close trade-based relations were established between Portugal and the Kongo Kingdom. However, the Portuguese, who initially hoped to find gold, soon discovered that slaves were the most valuable commodity.

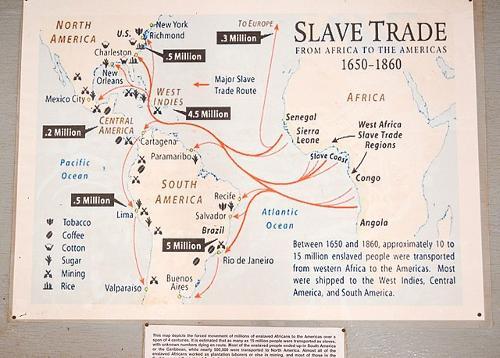

Portugal's greed for slaves slowly destabilized the kingdom as the settlers ignored the authority of the 'manikongos' and the slave traders became increasingly demanding and violent. By 1520 most of the missionaries had returned to Portugal. Fractions within the kingdom revolted repeatedly, driven by a desire to gain control of the lucrative slave trade, eventually culminating in an attack that drove the king, Álvaro I, into exile. The Portuguese, fearing not to lose their trading interests, responded by sending troops and eventually put an end to the revolt. They consolidated their position and occupied the area, extending their sphere of influence further south. During this period and up to 1850, the slave trade dominated Portuguese relations with Angola and an estimated four million slaves were transported, mainly to Brazil, where high demand for sugar stimulated labor demand, and to the rest of the Americas.

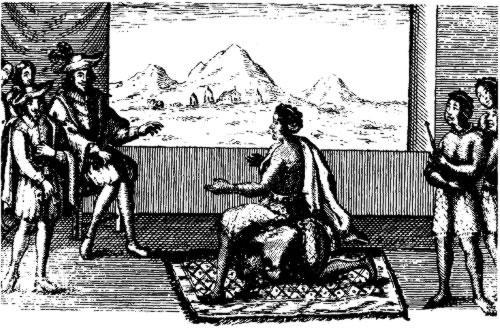

Angola Peace Negotiations Nzinga and PortuguesePhoto: Public domain

Angola Peace Negotiations Nzinga and PortuguesePhoto: Public domain

Portuguese Rule

In 1575, the Portuguese, led by the explorer Paul Dias de Novais, settled in Angola, in present-day Luanda. From this base on the coast, Portugal ran a thriving slave trade.

De Novais was a grandson of the famous Portuguese navigator Bartolomeu Dias who was himself an accomplished explorer, having first visited Angola in 1560. In 1571, King Dom Sebastião of Portugal sent him to Angola. He appointed him conqueror and captain-governor of the Kingdom of Angola and gave him and his descendants the right to 35 leagues of land south of the Kwanza River and everything he could grab inland. But on balance, the contract concluded with the king was little: he was only allowed to exercise his acquired rights for 12 years, he had to build three fortresses and establish a hundred families in the first six years. He was also not allowed to export slaves.

Bartolomeu Dias, first visited present-day Angola in 1560Photo:PH Parsons CC 3.0 no changes made

Bartolomeu Dias, first visited present-day Angola in 1560Photo:PH Parsons CC 3.0 no changes made

The Novais set out for Angola in search of precious metals, especially silver, which was rumored to be found in vast quantities at Cambambe on the Kwanza River. In February 1575, he arrived with his fleet of seven ships at Ilha, an elongated island a few meters from the current town of Luanda. As his contract dictated, he had brought 100 settler families, including merchants and priests, plus 400 soldiers; they camped on the Ilha. Forty Portuguese refugees from Congo and three thousand 'muxiluandas' (local residents) already inhabited the Ilha. The Ilha stretched for several miles, and combined with the bay it formed a safe harbor for his ships. Fresh water was readily available on the mainland, and the coastal plateau provided easy access to the interior and, he hoped, to the fabled silver deposits. But sandy Ilha had its drawbacks: it was unstable, difficult to defend and mosquitoes were a real scourge. So the Novais moved to the mainland the following year and established a settlement on the Morro de São Paulo, a low hill where the Fortaleza de São Miguel now stands. He encountered little opposition from the native Kongo tribes and fishermen and soon gained control of the surrounding area. The settlement would later become the village and then the (capital) city of São Paulo de Loanda (Luanda).

Loango Kingdom MapPhoto: Nerika CC 2.5 no changes made

Loango Kingdom MapPhoto: Nerika CC 2.5 no changes made

Dutch rule Luanda

The growing prosperity of Luanda attracted the interest of the greedy French, Spaniards and Dutch, who were bent on plundering raw materials and slaves from Africa. In August 1641, the Dutch WIC Admiral Cornelis Corneliszoon Jol (Scheveningen, 1597 - São Tomé, 31 October 1641), nicknamed "Houtebeen", invaded with his grand armada of 18 ships. The governor of Luanda gave the order to leave the city without a fight. The population fled north to one of the other fortresses that Paul Dias de Novais had built in Massangano. They took as much wealth and slaves as possible, but in the panic the government and city records were lost in the Bengo River. It is not known whether it was the mayor who dropped them in the river to lighten his load and facilitate his escape, or whether the Dutch later dumped them. Unfortunately, an important part of the city's history has been lost forever.

Loango-Angola coast in 1711Photo: Public domain

Loango-Angola coast in 1711Photo: Public domain

Earlier, in 1624, the WIC had already tried to capture the city of Luanda, where the largest slave depot of the Portuguese was located, but failed. The Loango-Angola coast became a colony of the West India Company (WIC) between 1641 and 1648 after the WIC conquered several towns and factories, settlements that acted as a base for overseas trade, from Portugal. In 1645 they made plans to build a canal from the River Kwanza in the south to bring much-needed water to the city. That plan came to nothing, however, as Salvador Correa de Sá e Benevides, sent by King Dom João IV of Portugal, successfully recaptured the city on the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin in August 1648. Salvador Correa de Sá e Benevides had done good things. in Brazil; he was an accomplished military man, both on land and at sea, and he was not a bad governor either.

João IV PortugalPhoto:Rick Morais CC 4.0 no changes made

João IV PortugalPhoto:Rick Morais CC 4.0 no changes made

The Dutch occupation of Luanda had cut off the supply of slaves to Brazil. Furious, Brazilian settlers raised money to mount a counterattack. In May 1648, Benevides set out with 1,200 men and 12 boats to recapture Luanda. Three or four months later he anchored his fleet at Kikombo, 15 km south of Sumbe. One of the ships had been lost in a storm, taking all 300 men with it. The anchor of that boat is in the Câmara Municipal in Sumbe. Undeterred by the loss of so many men, Benevides continued north as far as Luanda Bay. The Dutch mistakenly captured Miguel, making it easy for Benevides to take the fortress and the rest of the city the next morning. Benevides changed the name of the city from São Paulo de Loanda to São Paul da Assunção because 'Loanda' was too similar to 'Holanda'.

Fortaleza de São Miguel, AngolaPhoto: Erik Clevens Kristensen CC 2.0 no changes made

Fortaleza de São Miguel, AngolaPhoto: Erik Clevens Kristensen CC 2.0 no changes made

In recognition of his military success, Benevides was allocated large tracts of land and under his leadership began to repair the damage done by the Dutch. The Fortaleza de São Miguel, the Fortaleza do Penedo de Santa Cruz, several churches and the hospital were all restored. He also started the construction of the Cidade Baixa in Luanda in a more organized way. Other cities captured by the WIC were Benguela, Cabinda, Cambamba or Ensadeira Island, and Malembo; In addition, the J. van Roubergen, Corisco, Loango, Mayumba (also Majombo) and Soyo (also Mpinda) factories were opened, but these were abandoned in the course of time due to disappointing revenues.

19th and 20th century

Buoyed by their success against the Dutch, the Portuguese pushed further inland and conquered the states of Kongo and Ndongo. In the following centuries they expanded their control further east and unsuccessfully tried to gain complete control of the coast from Luanda to Cabinda. The slave trade was formally abolished by Portugal in 1836, but slavery continued in Angola, with slaves being used as laborers on coffee, cotton, and sugar plantations. Gradually slavery was replaced by forced labour, and this condition lasted until 1961.

Slave trade from Africa (including Angola) to North and South America (1650-1860)Photo: Jbdodane CC 2.0 no changes made

Slave trade from Africa (including Angola) to North and South America (1650-1860)Photo: Jbdodane CC 2.0 no changes made

In 1883 the Portuguese occupied Cabinda and annexed the region of the old Kongo Kingdom. At the Berlin Conference of 1884, Angola's northern borders were drawn and a year later the kingdom of Simulambuco formally ceded Cabinda to Portugal.

Despite the formal treaties, Portugal controlled only a small part of its territory with many independent kingdoms hostile to the Portuguese. Intensive military campaigns were necessary to conquer the pockets of resistance. A major campaign saved a Boer settlement near Humbe from attacks by Mandume ya Ndemufayo, the last king of the Kwanyama kingdom, a region separating the borders of Angola and Namibia. Another, and one of the most difficult campaigns, was waged against the Dembos people, who were attacked by the Portuguese for three years; they subjugated it in 1917 and did not conquer it until 1919. Systematic campaigns to conquer the neighboring kingdoms followed, and it was not until 1930 that the Portuguese could confidently say that they had all of Angola under control. From 1932 to 1974, the Portuguese dictator Salazar ruled and anti-colonial movements were brutally suppressed.

In 1951, the colony was granted Portuguese Overseas Province status and also became known as Portuguese West Africa. High coffee prices brought enormous wealth to the immigrants who had settled there and who continued to make big profits from it until independence.

Route to independency

The first nationalist movement to demand independence, the United Struggle for Africa Party in Angola, emerged in 1953. A few years later, in 1955, the Angolan Communist Party (Partido Comunista Angolano) was founded, followed around 1956 by the Marxist-Leninist Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA). The MPLA was composed of a number of smaller resistance movements and would later become the dominant party, taking power at independence and remaining in power to this day. The MPLA received support from the USSR and was led by Agostino Neto from 1962 until his death in 1979.

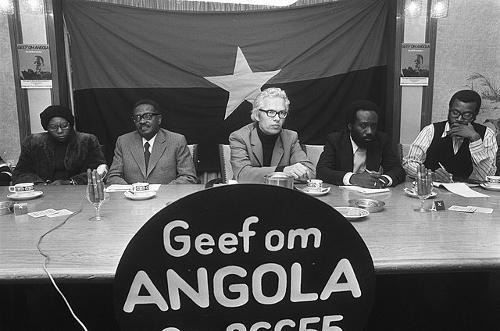

Agostinho Neto, president of Angolan liberation movement MPLA, in the NetherlandsPhoto: Rob Mieremet / Anefo in the public domain

Agostinho Neto, president of Angolan liberation movement MPLA, in the NetherlandsPhoto: Rob Mieremet / Anefo in the public domain

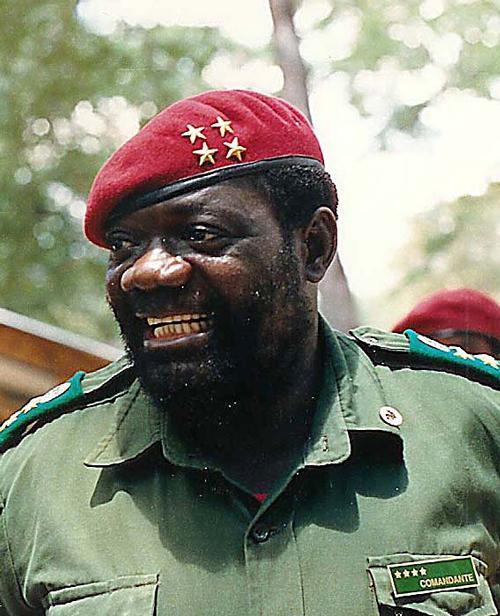

The second major movement, the Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola (FNLA), followed in 1961 and was supported by the Ovimbundu and South African apartheid regime. The leader was Holden Roberto, who was related by marriage to Mubutu Sésé Seko of Zaire. The movement would later disintegrate as Roberto refused to allow his organization to merge with other independence groups and is now a depleted political force. The last major player to emerge around 1966 was the União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (UNITA), backed by northern tribes and the anti-communist Western countries. After independence, UNITA waged a bloody war with the MPLA, which only ended after the violent death of its leader, Jonas Savimbi, in 2002. Almost immediately afterward, UNITA ended the violence and took part in mainstream politics. However, popular support was lacking and the party was crushingly defeated in the 2008 elections.

There were three factors that led to the beginning of the 30-year "Luta Armada de Libertação Nacional", the Angolan War of Independence; a major uprising of cotton workers in Malanje in January 1961; an attempt to free political prisoners from a prison in Luanda in February of the same year; and the brutal repression and massacre by the Portuguese in which thousands were killed or starved to death. Many others fled the violence and took refuge in Zaire. In the 1960s and 1970s, instability spread across Angola and independence groups became more organized, set up training camps, and sought foreign aid and finance. Their fatal mistake, however, was that while they had a common goal, Angola's independence, they were totally incapable of working together to achieve that goal. Personal power took precedence over the wider interest of independence and, as a result, internal bickering and tensions between different groups kept the guerrilla-level insurgency barely contained by the Portuguese army, with its superior firepower.

Exercise Angolan liberation movement FNLA in Zaire in 1973Photo: Rob Mieremet (ANEFO) CC 4.0 no changes made

Exercise Angolan liberation movement FNLA in Zaire in 1973Photo: Rob Mieremet (ANEFO) CC 4.0 no changes made

In April 1974, a nearly bloodless coup d'état ended nearly 50 years of dictatorship in Portugal. The "Carnation Revolution" sidelined Prime Minister Marcello José das Neves Alves Caetano Caetano (1906-1980), who then went into exile to Brazil, and he was replaced by General António de Spínola (1910-1996). In July of the same year, Spínola heeded the call from his weary military colleagues and the Portuguese people for an end to the bloody and costly Angolan war. He began to divest Portugal of all its African colonies; Portuguese East Africa followed in June 1975 and became Mozambique at independence, Cape Verde was next in July and Angola closed the ranks in November 1975. In the months following the coup in Lisbon, military actions against the Angolan nationalists were halted and Portugal recognized Angola's right to self-determination. Admiral António Alva Rosa Coutinho (1926-2010) was appointed High Commissioner in Angola and charged with overseeing Angola's transition to independence. The government of Spínola in Lisbon sought reconciliation between the three main liberation movements.

In January 1975, the three main independence movements, the MPLA, UNITA and FLNA, met in Kenya and agreed to work together as equal parties in a new government. They agreed to exclude FLEC, the Cabindan separatists, because FLEC did not support territorial integrity. On January 10, 1975, the three groups met in the Portuguese city of Alvor and signed the Alvor Agreement, whereby Angola would become independent on November 11, 1975, following elections in October 1975. In the meantime, a transitional government was to be formed, led by the Portuguese High Commissioner Rosa Coutinho and with the participation of the MPLA, UNITA and FNLA.

The transitional government was inaugurated on January 31, 1975, and foreign governments lined up to get involved. The United States gave $300,000 to the FNLA; the Soviet Union supplied weapons to the MPLA; the United States retaliated by giving more aid to the FNLA and funded UNITA for the first time; and Cuba sent troops and military advisers to assist the MPLA. The peace and harmony between the old rivals was short-lived and within days major quarrels led to renewed rifts. By March 1975, the Alvor Agreement had disintegrated and fierce fighting broke out in the streets of Luanda and later in the north of the country between the FNLA and the MPLA. The fighting made peaceful cooperation impossible and the fledgling government collapsed in July. The MPLA expelled the FNLA and UNITA from the capital and in turn the FNLA expelled the MPLA from the northern provinces of Uige and Zaire. Cuban military advisers arrived to assist the MPLA and Zairian troops moved into northern Angola to support the FNLA.

Meanwhile, South African troops occupy the Cunene region on the border with Namibia. Not surprisingly, the Portuguese got nervous and arranged an airlift in July to repatriate Portuguese workers. UNITA formally declared war on the MPLA on August 1, 1975. Portugal suspended the Alvor Agreement on August 14 and dissolved the transitional government. In theory, the Portuguese High Commissioner Rosa Coutinho took over all powers until independence, but in reality the MPLA seized as much power as it could. In the same month, UNITA attacked and shut down the economically important Benguela railway until partial repairs were made in 1978. A month before independence, South African troops, along with UNITA and the FNLA, advanced from Cunene province in the south to 100 km from Luanda. Elsewhere, the MPLA took control of 12 of the provincial capitals with the help of Cuban troops.

While the FNLA and UNITA, supported by South African troops, advanced on Luanda and MPLA troops defended the city with the help of the Cubans, the Portuguese High Commissioner could not leave soon enough. Rather than stay for a dignified and formal transfer of power, he shamefully handed over power to the Angolan people instead of a transitional government and fled on a Portuguese frigate.

On November 11, 1975, Independence Day, the MPLA, supported by tens of thousands of Soviet and Cuban troops, proclaimed itself the new government of the People's Republic of Angola and its leader, Agostinho Neto (1922-1979), became its first president. . UNITA and the FNLA licked their wounds. With covert financial support from the Americans and troops, weapons, fuel and food from South Africa, they agreed to set up an alternative coalition government of the Democratic People's Republic of Angola in Huambo. However, the FNLA and UNITA continued to bicker and only managed to set up a government in December, which, however, did not receive international support.

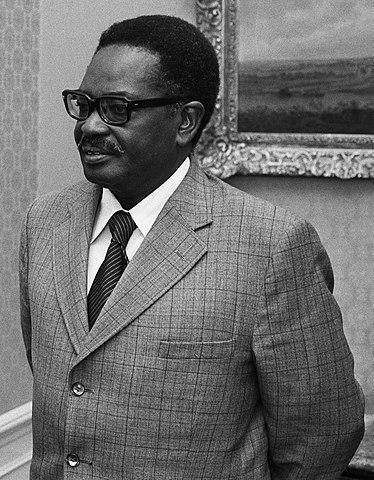

Agostinho Neto, first president of independent AngolaPhoto: Rob Mieremet / Anefo in the public domain

Agostinho Neto, first president of independent AngolaPhoto: Rob Mieremet / Anefo in the public domain

South Africa had become embroiled in Angola because the MPLA supported SWAPO (the South West African People's Organisation) in their struggle for independence in neighboring Namibia, while fighting communism in Angola, which became a common cause for South Africans .

By the end of a tumultuous year, more than 90% of white settlers had left Angola. With inappropriate behavior, they deliberately wrecked infrastructure as they left: wrecking plans, blowing up pumping stations, setting farms on fire, and even pouring cement down the drains of multi-storey buildings to render them uninhabitable. The struggle for independence from Portugal ended in 1975 and transitioned seamlessly into the Angolan Civil War.

Civil war

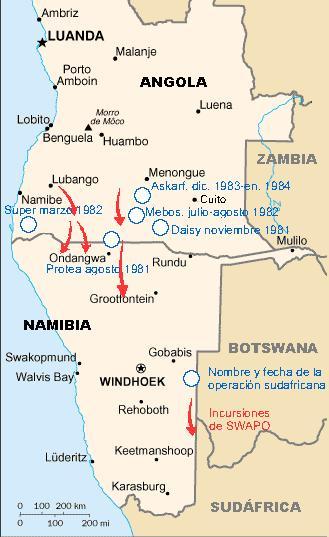

In January 1976, the MPLA was aided in its attacks on UNITA and its South African allies by Soviet airlifts of equipment and up to 12,000 Cuban troops. By February, the MPLA recaptured Huambo, Benguela, M'Banza Congo, Cabinda and Soyo. Under international pressure, South Africa withdrew its troops and the United States withdrew its financial and technical assistance. The Organization of African Unity recognized the MPLA as the legitimate government of Angola, along with the United Nations, Portugal and more than 80 other countries, but not the United States. In 1978, believing that a SWAPO training camp was operating in Cassinga, Huíla Province, South Africans carried out a deadly attack, killing hundreds. In August 1981, they again invaded southern Angola to pursue SWAPO insurgents. In February 1984, Angola and South Africa agreed on a ceasefire, the withdrawal of South African troops and the removal of SWAPO from the border area. The execution lasted more than a year, but the agreement was short-lived and in 1985 South African forces invaded again. In 1986, the United States began providing covert military assistance to UNITA as part of its global strategy to support anti-communist movements. This assistance enabled UNITA to extend its guerrilla warfare to over 90% of the country.

Operations of the SWAPO and the South Africa Defense Force in Angola and Namibia, 1981-1984Photo: Ceresnet CC 2.5 no changes made

Operations of the SWAPO and the South Africa Defense Force in Angola and Namibia, 1981-1984Photo: Ceresnet CC 2.5 no changes made

In July 1987, the Angolan army, with the help of the Cubans and the Soviets, launched a major offensive against Jonas Savimbi's UNITA forces in Cuando Cubango Province. The aim was to destroy UNITA's base in Jamba and drive the South Africans out of Angola. When the offensive began to succeed, the South Africans, who controlled the lower parts of southwestern Angola, intervened, as they had to ensure that UNITA maintained control of the areas bordering Namibia, as this would prevent SWAPO guerrillas from gaining access. springboard in southern Angola from which they could launch attacks in Namibia. The MPLA called for help and the response was tremendous. The Cubans sent hundreds of tanks, artillery, anti-aircraft guns, planes and nearly 50,000 men. The Russians contributed with military advisers, ships and transport. From 1987 to 1988, the small garrison town and air base of Cuito Canavale and nearby Mavinga had the dubious honor of being the largest tank battle since World War II and the bloodiest of the entire Angolan Civil War. Government losses are estimated at 4,000 killed and wounded. Cuito Cuanavale was the battle no one won, though both sides claimed victory. However, it was a turning point in the civil war and eventually led to the departure of Cuban, South African and other foreign troops from Angola.

In June 1989, after a meeting of 17 African countries, President Dos Santos of the MPLA and Jonas Savimbi of UNITA met under the auspices of Zairean President Mobutu Sésé Seko and agreed a ceasefire, but this ceasefire fires collapsed within two months and the war resumed.

Jonas Savimbi AngolaPhoto: Savimbi CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Jonas Savimbi AngolaPhoto: Savimbi CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

In the course of 1990 several rounds of talks between the government and UNITA took place in Lisbon and in May 1991 the Bicesse Agreements were signed in the Portuguese seaside resort of the same name. This latest peace deal sparked mass hope and optimism as a new multi-party constitution, a merger of the MPLA and UNITA armies, and elections were proposed. The very first elections were held from September 29 to 30, 1992 and were declared generally free and fair by the United Nations. In the presidential election, MPLA candidate José Eduardo dos Santos won 49.6% of the vote while UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi took 40% of the vote.

Presidential election results in Angola (1992)Photo: Felipe Rey CC 4.0 no changes made

Presidential election results in Angola (1992)Photo: Felipe Rey CC 4.0 no changes made

In the parliamentary elections, the MPLA won 129 out of 220 seats; UNITA won 70 and ten smaller parties divided the remaining 21 seats. However, as neither party had obtained the required 50% of the vote, a runoff was held. Savimbi resigned on charges of electoral fraud and irregularities and returned to war. In the following month, fierce fighting erupted in Luanda and nearly wiped out UNITA's leadership in the capital. The country was once again thrown into violent fighting and within months UNITA had taken control of much of the interior. During the next two years of fighting, about two million people were displaced from their homes and more than 20 million land mines were laid. In January 1993, UNITA took the strategically important oil city of Soyo, leading to the intervention of the private military company Ececutive Outcomes, on the side of the government. That same year, the siege of Huambo in the center of the country began, lasting 55 days and claiming tens of thousands of lives.

By the end of 1993, UNITA controlled about 70% of the country and 1,000 people were starving to death every day. In November 1994, President Dos Santos and Jonas Savimbi signed a new peace agreement, this time in the Zambian capital Lusaka. Two days later, a formal ceasefire was declared.

The Lusaka Protocol, as it has come to be known, contained a series of measures to end the civil war. It called on UNITA to demobilize and give up areas under its control, establish a national army, and establish a Government of National Unity and Reconciliation (GURN). In return, UNITA would take the 70 seats it would have had had it accepted the 1992 election results and Savimbi would become vice president of Angola. United Nations peacekeepers were deployed, but they were ineffective. But this deal also broke down due to mutual mistrust. While the government generally adhered to the protocol's obligations, the demobilization was delayed and Savimbi was hesitant to give up the diamond-producing areas under his control that provided him with the money to continue fighting. In 1995, a United Nations Security Council resolution approved the deployment of a 7,000-strong peacekeeping force, the United Nations Angola Verification Mission (UNAVEM), to monitor the implementation of the Lusaka Protocol, in particular the demobilization of the troops on both sides. This included the gathering of UNITA troops in cantonment areas and the selection of 26,300 UNITA troops to join the Angolan Armed Forces.

In April 1997, the MPLA-dominated GURN was installed, transforming UNITA from a military group into a political party and holding four ministerial posts. Other political parties, both within and outside the National Assembly, were numerous and exercised very little influence. The GURN was, to a large extent, a rubber stamped government, only reluctantly challenging the executive. In June 1997, the United Nations Security Council dissolved UNAVEM and replaced it with a civilian observer mission, the Mission d'Observation des Nations Unies en Angola (MONUA). MONUA was given a seven-month mandate to monitor compliance with the obligations of the Lusaka Protocol. UNITA reacted very slowly and the Security Council imposed sanctions against them in 1997.

In the years that followed, the guerrilla war continued, punctuated by conversations, agreements and misunderstandings, reproaches and mutual and deeply felt mistrust. UNITA moved with impunity in the countryside, controlling about half of Angolan territory, while the MPLA controlled the cities. In January 1998, the United Nations Security Council approved an extension of the mandate of the UN peacekeeping mission in Angola. Several more extensions followed, but after the last one expired in February 1999, MONUA was withdrawn as there was no longer a credible peace process for them to oversee.

21th century

In 1998, the MPLA mounted a major offensive against UNITA, and in February 2002, it finally came to an end when Jonas Savimbi, UNITA's charismatic and brutal leader, was killed by government forces during a commando raid in Moxico province. The following month, the government announced a ceasefire and proposed plans for amnesty, demobilization of UNITA troops and rehabilitation of UNITA into a mainstream political party. Nearly 30 years of bloody conflict came to an end for most Angolans. However, the uprising in Cabinda continued until a memorandum of understanding was signed with part of the Cabindan separatist movement, Frente para a Libertação do Enclave de Cabinda (FLEC). Nearly 30 years of bloody conflict came to an end for most Angolans.

Proposed flag for the Republic of CabindaPhoto: AsthmaGuy CC 4.0 no changes made

Proposed flag for the Republic of CabindaPhoto: AsthmaGuy CC 4.0 no changes made

First free elections since 1992

New electoral laws were introduced in April 2005 and elections were promised for 2006, but these were repeatedly postponed as mines had to be cleared and roads and railways repaired to allow more people to vote. In the run-up to the election, there was a widespread belief that the political scene had evolved a lot since the last failed election and that all parties had truly committed themselves to peace, and no one really believed that a return to war was possible. Elections were finally held in September 2008, the first since September 1992, and for many Angolans it was the first election they had ever participated in. The elections were peaceful and, despite some administrative difficulties, were widely accepted by the international community.

Landmine Victim, AngolaPhoto: Ton Rulkens CC 2.0 no changes made

Landmine Victim, AngolaPhoto: Ton Rulkens CC 2.0 no changes made

UNITA complained of harassment from its members. She also expressed concern about the logistical arrangements made for the elections and the unequal access to funding and publicity for opposition parties. The MPLA received 81.6% of the vote and won a convincing majority of 191 of the 220 seats in the National Assembly. UNITA was crushingly defeated by just 10.3% of the vote and only 16 seats, significantly reducing its representation in the National Assembly from the 70 seats it previously held, and is struggling to redefine itself as a credible political side.

The lead-up to the August 2012 elections was marked by a series of protests in Luanda, including in neighborhoods popular with expats such as Miramar, Maianga and Cidade Alta, as well as in other cities. Many of the factors that sparked popular uprisings in the Arab world in 2011 and 2012 were present in Angola: an alleged kleptocracy, corruption, an oppressive regime, wealth unequal distribution, poor social conditions and censored media. Encouraged by news reports and exaggerated in countless text messages and social media sites, a series of unprecedented and furious protests took place, especially in Luanda, but also in other cities.

Protesters openly questioned the legitimacy of former President dos Santos, anti-establishment rappers were beaten up and Luaty Beirão, a famous rapper and activist, was arrested in Portugal on what is believed to be a trumped-up drug charge. The authorities' response included violent clashes, arbitrary arrests and beatings of detainees. The authorities targeted journalists and made it very difficult for the independent media.

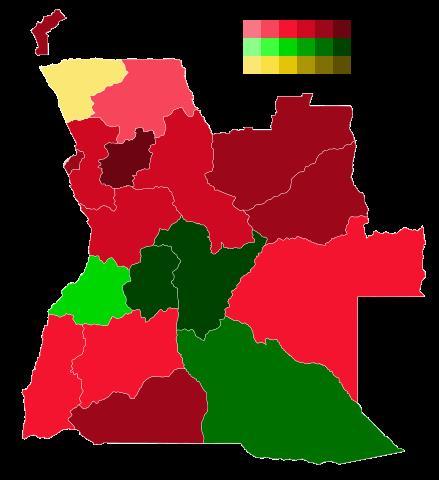

Angola general elections in 2008 in 2012 were won in all provinces by the MPLAPhoto: Felipe Rey CC 4.0 no changes made

Angola general elections in 2008 in 2012 were won in all provinces by the MPLAPhoto: Felipe Rey CC 4.0 no changes made

The National Commission (CNE) itself became controversial over the qualifications and impartiality of its head, who was eventually impeached, and over the accreditation of international observers. It was therefore not surprising that there was a lot of confusion on the day of the vote, as many votes were rejected because they were not on the lists, or because they were told to vote at polling stations many hours away . There were delays in opening and closing polls and a large polling station in the Luandese suburb of Viana did not open at all, depriving all voters of the right to vote.

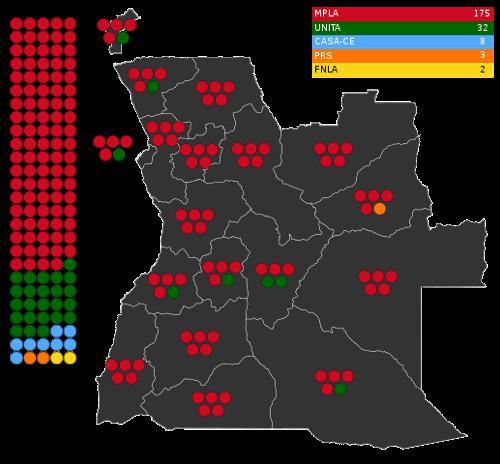

International observers gave the election an overall unqualified verdict, saying it was free and credible and pointing out the logistical challenges the CNE was facing. The results were no surprise. The ruling party MPLA received 71.8% of the vote, 10% less than in 2008, but still a large majority, which translated into 175 seats in parliament. UNITA won 18.66% of the vote, which equated to 32 seats, a marked improvement on the previous election.

Newcomer CASA-CE, which was founded just six months before the elections, won a very respectable 6% of the vote and 8 seats. Turnout was about 63%, down almost 20% from 2008, due to widespread cynicism towards the ruling party and the electoral process. After the 2010 constitutional amendment, the leader of the winning party automatically becomes head of state and the second is named vice president. José Eduardo dos Santos was thus elected president with former Sonangol head (Angolan state company involved in oil and gas extraction) Manuel Domingos Vicente as his deputy,

Dos Santos and Lula, AngolaPhoto: Wilson Dias CC 3.0 no changes made

Dos Santos and Lula, AngolaPhoto: Wilson Dias CC 3.0 no changes made

he 2012 elections were widely expected to culminate in President dos Santos' last term in office, given his age and reportedly ongoing health problems. Dos Santos intended to use this final four-year term to legitimize his rule and then transfer power to Vicente, while still retaining significant influence and protecting his family's interests. However, in the second half of 2014, global oil markets began to tilt. In June 2104, the OPEC reference basket for oil averaged $107.89 per barrel. This was a disaster for Angol, which relies on oil sales for a quarter of its GDP and more than 90% of its total exports. Inflation and unemployment rose, construction projects came to a standstill, there was a shortage of US dollars in Luanda and many members of the oil industry lost their jobs. The rest had to work for months without pay due to the shortage of US dollars, and the companies found it increasingly difficult to repatriate their profits.

The oil price crash clearly showed how poorly diversified the Angolan economy was, despite all the talk about the growth of the non-oil sector after a similar price shock in 2008-2009. With Sonangol on the brink of bankruptcy, confidence in Vicente began to crumble. To make matters worse, in June 2016, President Dos Santos appointed his daughter, Isabel dos Santos, head of Sonangol, amid widespread public outcry.

Manuel Domingos Vicente, vice-president of Angola (2012-2017)Photo: Michel Temer CC 2.0 no changes made

Manuel Domingos Vicente, vice-president of Angola (2012-2017)Photo: Michel Temer CC 2.0 no changes made

n 2016, it became clear that the Central Committee of the ruling MPLS had no intention of letting President Dos Santos resign on his own terms or imposing his successor on the party. After much backroom negotiation, João Lourenço was named vice president in August 2016. Lourenço, a soldier with strong credentials in the liberation struggle, has been defense minister since 2014.

A drought in 2016 caused southern Africa's worst food crisis in 25 years, affecting 1.4 million people in seven of Angola's 18 provinces. Food prices rose and acute malnutrition cases doubled, affecting more than 95,000 children.

In the early 2000s, when President Dos Santos first flirted with the idea of retiring, there was talk of him taking over the presidency. Lourenço's open interest in the top job, however, did not please the then president, who as a result forced him to spend nearly a decade in the political wilderness. It took a long time, but Lourençco got back into the fray in time for the 2017 parliamentary elections. Just before agreeing to his resignation, Dos Santos pushed his legislation through the National Assembly that would secure the jobs of top military, police and intelligence officials for eight years in a bid to prevent his successor from removing his supporters. once he was in power. This was a prescient attempt to maintain control, given what was to come.

The elections took place on August 23, 2017, with Lourenço at the head of the MPLA's list. The MPLA won easily with 61.1% of the vote, followed by UNITA with 26.7% and CSA-CE with 9.5%. However, it was not all good news. Voters were dissatisfied with the state of the economy. The MPLA's votes had fallen by 10% since 2012, causing the party to lose 25 seats in the 220-seat parliament.

More worryingly, the ruling party lost its majority in Luanda for the first time, taking only 48% of the vote. Opposition groups cried out and took their complaints about the handling of the elections to Angola's Constitutional Court, but to no avail. President Lourenço was sworn in as Angola's third president on September 26, 2017.

When President Lourenço took office, he faced a difficult task: an economy in crisis, a citizen who lost confidence in the ruling party and widespread, large-scale corruption. Many political commentators believed that he was not in a strong position to make radical changes, that he stood for continuity rather than change. His first year in office proved them wrong.

Three weeks after his appointment, President Lourenço ordered a major overhaul of the Angolan oil industry, in consultation with the country's multinational oil companies. He also announced a new competition law to dismantle many of the monopolies that stunted the growth of Angolan's economy, and appointed the internationally respected José de Lima Massano as head of the Central Bank of Angola. Almost immediately there was talk of calling in the IMF to help with Angola's dire financial situation and reduce their reliance on opaque Chinese oil-backed loans.

Isabel dos Santos, head of SonangolPhoto: Nuno Coimbra CC 4.0 no changes made

Isabel dos Santos, head of SonangolPhoto: Nuno Coimbra CC 4.0 no changes made

Less than two months after taking office, on November 15, 2017, President Lourenço fired Isabel dos Santos as head of Sonangol. This resignation sent a strong signal to vested interests within the government and was particularly popular in Angola, where Isabel's earlier appointment was regarded by her father as an example of nepotism. Isabel was not the only prominent displaced person: What has been described as a political purge to cement his power and diminish the influence of the Dos Santos family, Lourenço subsequently fired the head of the national police, Ambrósio de Lemos, and the head of the intelligence agency, Apolinário José Pereira. Both were considered allies of former President Dos Santos. In August 2020, José Filomeno dos Santos, son of Angola's former president, was sentenced to five years in prison for fraud and corruption. In the months that followed, members of the old regime continued to fall, earning Lourenço the nickname "Buldózer" in the domestic media. and "Terminator".

President Lourenço clearly intended to do things differently than his predecessor. There was a sharp contrast in his engagement with the Angolan people. Stories circulated that in October 2017 he had been spotted queuing at KFC, and that in June 2018 he was seen on a beach near Luanda with First Lady Ana Dias (himself an economist with experience at the World Bank and the IMF). among the public.

A drought in 2016 caused southern Africa's worst food crisis in 25 years, affecting 1.4 million people in seven of Angola's 18 provinces. Food prices rose and acute malnutrition cases doubled, affecting more than 95,000 children.

The relatives of former president Dos Santos were not happy with this turn of events and publicly spoke of being targeted because of their last name. On January 8, 2018, President Lourenço responded directly to these concerns in a public speech: "We are not prosecuting individuals, but situations that have been proven to be harmful to the public interests of the state." Three days later, he fired José Filomeno dos Santos ("Zenú"), who had been appointed chief of Angola's prosecutors and had opened a fraud investigation against Zenú, in connection with illegal transfer of $500 million from the sovereign wealth fund while he was under his leadership. was standing. In his most important step to limit the future influence of the dos Santos family in Angola, Lourenço took over the presidency of the MPLA on September 8, 2018, which José Eduaro dos Santos had held even after his resignation.

President Lourenço's fight against corruption was accompanied by efforts to reform the Angolan economy. Emphasis has been placed on more effective integration into the Southern African Development Community (SADC), as well as following IMF guidelines to move away from oil dependency. New visa rules were introduced in May 2018 to make it much easier for foreigners, especially other SADC citizens, to visit Angola. On August 20, 2018, Angola's Ministry of Finance announced that it would request a $4.5 billion bailout program from the IMF to help implement their Macroeconomic Stabilization Program (PEM) by 2022. In the past, these IMF support packages have been actively avoided as they come with significant transparency obligations. Once again, President Lourenço sent a clear message that this time it would be different.

In August 2020, José Filomeno dos Santos, son of Angola's former president, was sentenced to five years in prison for fraud and corruption.

João Lourenço, president of AngolaPhoto: Jérémy Barande CC 2.0 no changes made

João Lourenço, president of AngolaPhoto: Jérémy Barande CC 2.0 no changes made

n 2021, as a result of the revision of Article 100 of the Constitution of the Republic of Angola, the Banco Nacional de Angola obtained the status of an independent monetary authority. The next parliamentary and presidential elections are expected to take place in August 2022.

Angola plans to run a metro in the capital Luanda. German transport company Siemens Mobility will build the light rail, which is expected to start construction in 2022, as part of a public-private partnership. The route is estimated to be 149 km long and cost approximately $3.5 billion.

Angola received the first shipment of vaccines against Covid-19 in March 2021, 624,000 doses of the vaccine developed by Oxford/Astrazeneca, produced in India and donated under COVAX, a World Health Organization (WHO) initiative.

With the vaccines, Angola has become the third African country, after Ghana and Ivory Coast, to receive the COVAX shipments. Angola has so far, July 17, 2022, counted 1,900 deaths and 99,761 cases of covid-19 since the start of the pandemic in 2020.

José Eduardo dos Santos, once one of Africa's longest-serving rulers, who for nearly four decades as president of Angola fought the continent's longest civil war and made his country a major oil producer, but also one of the world's poorest and most corrupt nations, died on Friday, July 8, 2022. He was 79 years old and died in a clinic in Barcelona, Spain.

Sources

BBC - Country Profiles

CIA - World Factbook

Elmar Landeninformatie

Oyebade, Adebayo / Culture and customs of Angola

Greenwood Press

Stead, Mike / Angola

Lonely Planet

Copyright: Team The World of Info