SOUTH AFRICA

History

History

Cities in SOUTH AFRICA

| Cape town | Johannesburg |

History

Oldest inhabitants

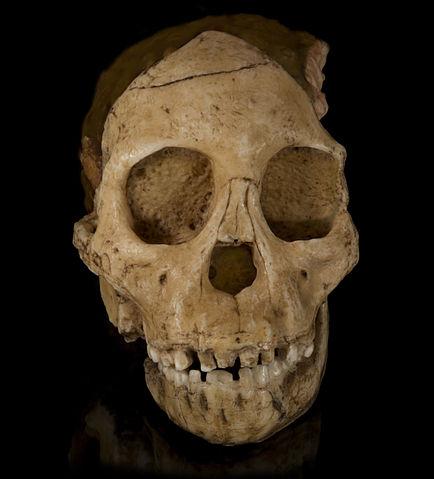

People lived in South Africa more than two million years ago. They were Stone Age hunters. Bones found at Taung in the North Cape and Sterkfontein near Johannesburg are evidence of this. These hunters left over the years or died out around the year 200.New groups came to the original inhabitants of South Africa, the San (collectors) or Bushmen and Khoikhoi (herders) or Hottentots, who came from the Great Lakes region in Central Africa. Together the two peoples were called the Khoisan and they are often considered to be the oldest inhabitants of South Africa.

Skull of Taung-child, South AfricaPhoto: Didier Descouens CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Skull of Taung-child, South AfricaPhoto: Didier Descouens CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Centuries later, the Nguni descended to Southern Africa. They were the ancestors of black peoples like Xhosas and Zulus, both Banto people. These peoples, mainly livestock farmers and arable farmers, stayed in one place for much longer and were therefore able to develop better and soon expanded their residential area at the expense of the Khoisan.

With the arrival of Europeans in the 17th century, not much remained of the Khoisan; among others due to smallpox epidemics. The Hottentots live on in tribes like the Nama and the Griekwa, while the Bushmen live in Botswana and Namibia, near the Kalahari Desert.

Portuguese and Dutch

In 1488 the Portuguese Bartholomeu Diaz was the first European to sail around the Cape Peninsula and in 1498 the famous Vasco da Gama followed. The Portuguese used the Cape as a place to stock up on fresh water and food. At the end of the 16th century, the first Dutchman rounded the Cape, Jan Huygen van Linschoten. In the early 17th century, many ships of the United East India Company (VOC) followed. They also used the Cape as a resting point on their way to the east. The first permanent residents were those on board the ship "Haarlem", which was wrecked in Table Bay in 1648. After a year they returned to Holland.

The Dutch East India Company decided in 1651 that a permanent oil change station should be built on the Cape and sent the ship's doctor Jan van Riebeeck on the road. On April 6, 1652, he founded an infirmary and a station at the Cape of Good Hope where provisions could be taken. Grains, vegetables and fruit were also grown and some cattle were kept.

Jan van Riebeeck, founded the first European tradingpost in South AfricaPhoto: Public domain

Jan van Riebeeck, founded the first European tradingpost in South AfricaPhoto: Public domain

After the Van Riebeeck period, the area was governed by some thirty commanders, governors and commissioners, the best known of whom were Simon van der Stel (1679-1699) and W.A. van der Stel (1699-1707). From 1657, civil servants but also farming families from Holland were allowed to settle as "free citizens" at the Cape. Many Dutch peasant families took advantage of this and, stimulated by favorable conditions, a prosperous agricultural colony was created. However, South Africa has never been a colony in a formal sense. Slaves from East Asia and West Africa were brought in as workers in the same year. From 1685, Huguenots also came to the Cape who initially lived peacefully together with the Dutch, the slaves and the Khoisan. Together with the Dutch, the Germans and the French, the "Afrikanervolk" was created.

Conflicts with the Khoisan due to the expansionism of Europeans increased rapidly, forcing the Khoisan to withdraw into the empty areas of the Cape Colony. Due to the expansion of the area to the east, the Europeans first came into a bloody conflict with the Banto people like the Xhosa. In total, nine of these so-called Kaffir Wars would be fought.

Within fifty years of the creation of the agricultural colony, a serious clash between Governor W.A. van der Stel and the Afrikaners, who were only limitedly represented in the central government bodies and demanded self-government on a number of occasions for the colony at the Cape.

Simon van der Stel, first governor Cape of Good Hope, South AfricaPhoto: Public domain

Simon van der Stel, first governor Cape of Good Hope, South AfricaPhoto: Public domain

South Africa under British rule

When this was refused by the VOC, and in 1784 also by the States General, they in February 1795 in the districts of Graaff-Reinet and Swellendam shed the authority of the VOC and placed themselves under a "kind of independent constitution" directly under the authority of the Dutch Republic. The heyday of the VOC had already ended and in 1791 the VOC had already withdrawn from South Africa. The first occupation of the Cape by Britain in 1795 put an end to the existence of the "independent" states. In 1803, under the Treaty of Amiens, the Cape still came under the authority of the Batavian Republic, but in 1806 Britain conquered the area again and in 1814 acquired it permanently.

When the British arrived in the late 18th century, approximately 6,000 Dutch, 5,600 Germans and 2,400 French lived in South Africa (together referred to as Boers or Afrikaners). Furthermore, about 15,000 Khoisan and 25,000 slaves lived there.

Under the British administration, the economy received strong impulses from wine growing and the export of wool. Outside of Cape Town, the free-spirited Peasants strongly opposed the strict rules that the British tried to impose on them. Relations with the Bantoevolk also left a lot to be desired when the settlers were offered Bantoeland as agricultural land.

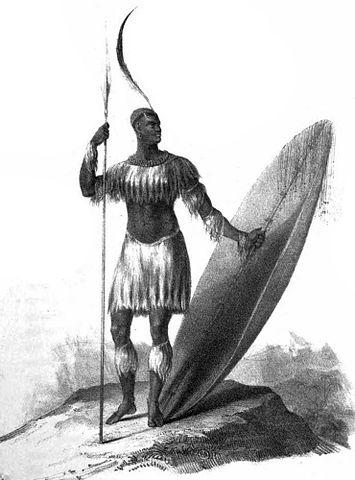

At the end of the 18th century, tensions arose between the different population groups due to the growing population and the subsequent pressure on livelihoods. The Banto peoples also fought regularly with economic resources as their stake. The Zulus led by Shaka Zulu managed to expand their territory and the other Banto people were driven out.

Image of Zulu king Shaka Zulu, South AfricaPhoto: James King in the public domain

Image of Zulu king Shaka Zulu, South AfricaPhoto: James King in the public domain

As a result of these wars, the north and northeast became depopulated and other tribes (including Sotho and Swazi) retreated to the mountains and formed different kingdoms there. In 1828, Shaka was murdered by his brother Dingane.

The Boers also had an increasing need for a new country and wanted to come under the pressure of the British. The Boers also had serious objections to the proclamation of English as the only official language and as the only language of instruction in education. The abolition of slavery and the settlement of 5,000 British emigrants in the Cape Colony also caused bad blood.

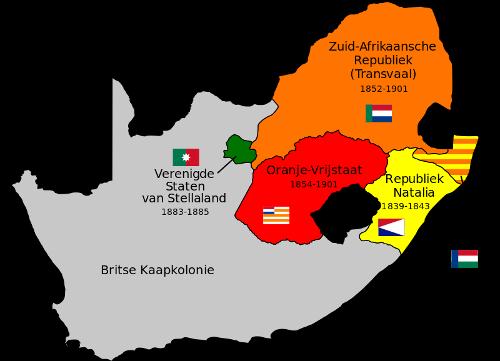

After the Sixth Kaffer War with the Xhosa in 1834, the Boers, also known as Voortrekkers, went to the north with ox carts (later the symbol of the struggle for independence) (Great Trek). Conflicts with the Ndebele and the Zulus were resolved in favor of the Boers and after the Battle of the Blood River with the Zulus, parts of Natal were seized. Here the Boers founded the republic of Natalia, which was ruled by an elected People's Council. Boer Republics in South Africa, end 19th centuryPhoto: Master Uegly CC 4.0 International no changes made

Boer Republics in South Africa, end 19th centuryPhoto: Master Uegly CC 4.0 International no changes made

Britain began to break up that republic since 1842: in 1842 through the conquest of the region east of the Drakensberge (Natal) and in 1846 through the annexation of the region south of the Vaal River under the name "Orange River Sovereignity" . In 1848 the Boers tried unsuccessfully to relocate to the area.

Yet they could not prevent the Boers from establishing their own republics in Transvaal (1852) and Oranje Vrijstaat (1854). Independence by Great Britain was guaranteed and recognized in two tracts, respectively. the Zandrivier Convention and the Bloemfontein Convention. Great Britain replied by declaring Natal as an official colony in 1856. Great Britain soon no longer respected the provisions of the said tracts, as evidenced by the annexation of Basoetoland (1868), of the Transvaal and especially Frystaat diamond fields (1871) and eventually from the South African Republic itself (1877) after the discovery of the Lydenburg goldfields.

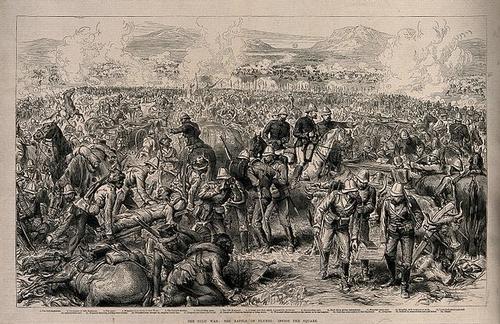

The Boers and the British also regularly fought conflicts with the Banto people; the Boers with the Sothos and the British fought a war with the Zulus who were settled in favor of the British in 1879 during the Battle of Ulundi. In 1887, the British annexed Zululand.

Battle of Ulundi (1879), South AfricaPhoto: Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0) no changes made

Battle of Ulundi (1879), South AfricaPhoto: Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0) no changes made

Boer Wars

They also wanted to improve the position of the black population. There the Boers led by Paul Kruger rebelled in 1880 and the first Boer War was a fact. In the Battle of Majuba Hill, the British were defeated, the Boers regained Transvaal in 1881, and Paul Kruger became president of an autonomous Transvaal. Meanwhile, the Germans had settled in Southwest Africa (now: Namibia) and the British were afraid that they would conspire with Transvaal.

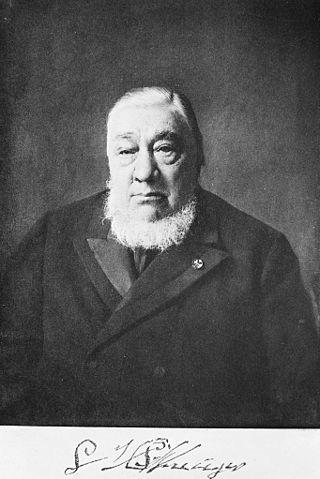

Paul Kruger, president of Transvaal, South AfricaPhoto: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/amjsrqbx CC-BY-4.0 no changes made

Paul Kruger, president of Transvaal, South AfricaPhoto: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/amjsrqbx CC-BY-4.0 no changes made

To this end, the protectorate of Bechuanaland (now: Botswana) was proclaimed in 1885 with Cecil Rhodes in charge. Together with his British South African Company, he tried to realize a British corridor from the Cape to Cairo in Egypt. Before that he also colonized the area of Rhodesia, present-day Zimbabwe and Zambia. In order to further realize his ideals, it was necessary for South Africa to be governed centrally, and of course an autonomous Transvaal did not fit in with that. In addition, gold had been discovered in Witwatersrand in 1886, and the economic center of gravity shifted from the Cape to more northerly Johannesburg.

As a result, the British lost more and more authority and Rhodes, together with fellow countryman Jameson, tried to overthrow the Boer authority in Transvaal. However, this so-called Jameson's Raid in 1895 completely failed.

In 1899, after a long diplomatic dispute, the British again declared war on the Boers (second Boer War). The Boers defended themselves vigorously, but due to lack of food and lack of aid, the Treaty of Vereeniging was concluded and the Orange Free State and Transvaal came under British authority, but remained largely self-governing.

Paul Kruger could not handle this situation, left for the Netherlands and was succeeded by Colonel Jan Smuts. In 1910 Transvaal, Cape Colony, Orange Free State and Natal united in the Union of South Africa and Louis Botha became the first Prime Minister.

General Louis Botha, first prime-minister of South AfricaPhoto: IWM Collections in the public domain

General Louis Botha, first prime-minister of South AfricaPhoto: IWM Collections in the public domain

To satisfy both the Boers and the British, it was decided to establish the parliament in Cape Town, the government in Pretoria and the Supreme Court in Bloemfontein. The union remained part of the British Empire, but decided on domestic affairs. The position of the non-whites deteriorated. Banto areas such as Transkei and Swaziland gained special status and Natal was annexed by farmers. At the end of the 19th century, non-white populations were not allowed to settle just anywhere. Protests against this manifested themselves in the non-violent resistance of the Indians led by Mahatma Gandhi. The Africans were dissatisfied with the reconciliation policies of Botha and his South African Party (SAP). Figures such as General Jan Hertzog were dissatisfied with the British dominance in the economy and against his striving for equivalence between "that black danger" and the white population. The founder of the black ANC (African National Congress) added fuel to the fire and Hertzog founded the Nasionale Party, and split off the SAP.

In World War I, Botha supported Britain, which again sparked anti-British sentiments. Republican thought re-emerged: South Africa, separate from Britain, could remain outside British wars. Furthermore, German Southwest Africa was attacked and the government took over there. This led to the "Rebellion", in which the generals Beyers, De la Rey, De Wet and Kemp took part. The rebellion failed, but it strengthened the ranks of the Nasionale Party.

After World War I, Southwest Africa became a union mandate with the permission of the League of Nations (now: United Nations). After Botha's death, Jan Smuts succeeded him in 1919 and again three years later, Smuts was succeeded by the nationalist Hertzog, under whose rule the African officially became the second language. Under his rule, the seeds of apartheid were sown. He sought greater independence from Britain and limited the freedoms of the non-white population. In 1926 at a Reich conference in London, he was able to express the famous formula that within the British Empire both Britain and the Dominions would be autonomous and equal communities, voluntarily associated under the Crown.

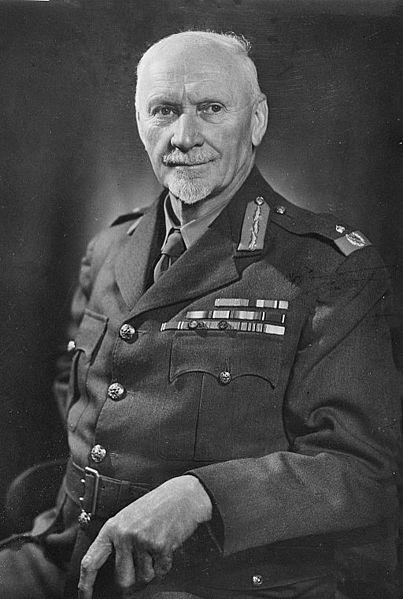

Jan Smuts (1870-1950), general, statesman and philosopher, South AfricaPhoto: Unknown CC 3.0 Nederland no changes made

Jan Smuts (1870-1950), general, statesman and philosopher, South AfricaPhoto: Unknown CC 3.0 Nederland no changes made

In the 1930s, when South Africa was also hit by world depression, Smuts' Suid African Party merged with Hertzog's Nasional Party to form the United Party. Some nationalist hardliners immediately separated and founded under the leadership of D.F. Malan de Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party, the most important organ of which is the Broederbond. General Hertzog became leader, General Smuts became leader. In the midst of this development, Britain's declaration of war on Germany came in early September 1939. A proposal by General Hertzog to remain neutral was rejected and a proposal by General Smuts to declare war was adopted. The governor-general declined to dissolve parliament, thanked Hertzog as prime minister, and Smuts became prime minister of a coalition cabinet that included all parties except the Malan Nasional Party, which now included Hertzog (temporarily) and a large number of his followers, who was given the name Reunited Nasionale Party. In World War II, South Africa played an important military role both in Africa (including in Ethiopia) and in Europe (Italy).

Apartheid becomes government policy

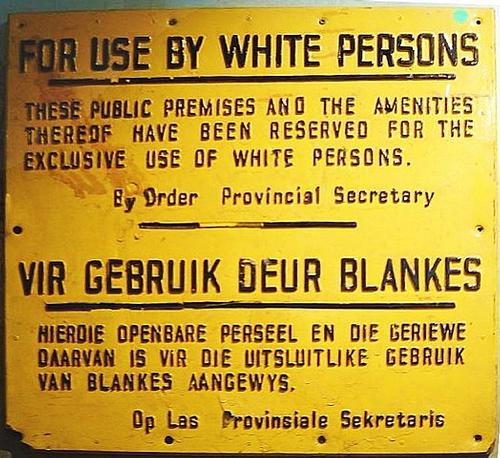

After the war, the United Party enacted some repressive laws that received much support from the white population. The other population groups were, of course, less enthusiastic about this and the resistance against it quickly took shape. Smuts therefore lost more and more prestige due to the increasingly powerful position of the non-white population. The white people saw their privileged position increasingly jeopardized and moved more and more to Malan, who won the elections in 1948 and was able to start with the detestable apartheid policy. Example of Apartheid in South AfricaPhoto: Dewel in the public domain

Example of Apartheid in South AfricaPhoto: Dewel in the public domain

His idea was to let the various population groups live in separate residential areas so that they would retain their own identity. Initial opposition to these plans and their implementation was unstructured and marginal. Only in 1952 did the ANC organize a "National Disobedience Campaign". In 1955, the Congress of the People, protest organizations of all races and colors, adopted the Freedom Manifesto. It stated that South Africa belonged to all populations (including whites) and that political power should also be distributed among the populations. This freedom manifesto would henceforth serve as a charter for the ANC. However, the ANC was also divided. In 1959, the Pan Afrikanist Congress (PAC) was founded by a group of ANC people who felt that there could be no room for whites in the ANC.

Among the successors of Malan (limited voting rights for colored people), Johannes Strijdom in 1954 and Hendrik Verwoerd in 1958, his policy to allocate blacks to independent home countries and to no longer have representatives in the South African government continued, and the position of the whites grew stronger and stronger. In 1961, therefore, only the white population was consulted about the relationship with Great Britain. The vast majority chose independence and South Africa was declared a republic.

1961 was also the year of "Sharpeville", where a demonstration by the PAC against Pass Laws left 69 dead.

Mass graves Sharpeville, South AfricaPhoto: Andrew Hall CC 4.0 Internationaal no changes made

Mass graves Sharpeville, South AfricaPhoto: Andrew Hall CC 4.0 Internationaal no changes made

The government declared a state of emergency, ANC and PAC were banned, and the power of the army and police grew. Both the PAC and the ANC were forced to establish an underground military department that violently opposed apartheid policy. However, important black leaders like Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu were captured and sentenced to life in 1963, weakening the black opposition in the 1960s. Prime Minister Verwoerd was assassinated in 1966.

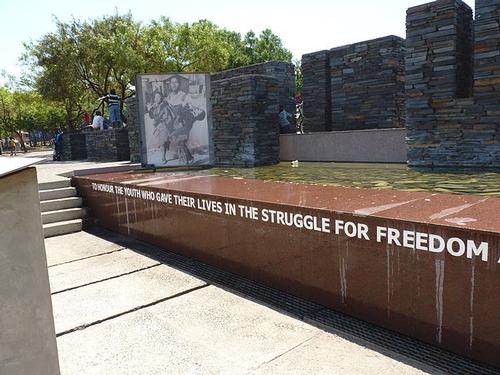

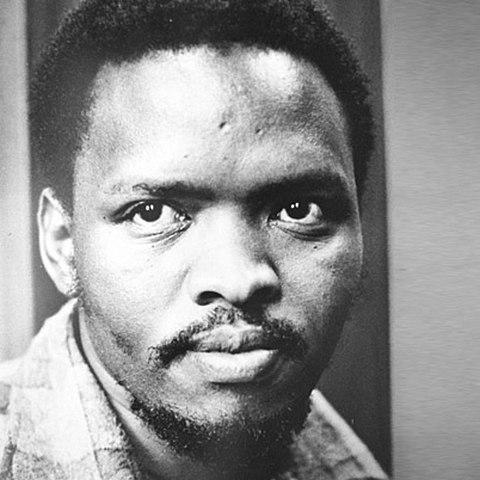

His successor, J.B. Vorster, as Minister of Justice, had been responsible for legislation to combat the opposition to apartheid and was now implementing the homeland policy designed by Verwoerd to shape territorial segregation. In the early 1970s, the black opposition recovered again through the founding of Steve Biko's Black Consciousness Movement and a strengthening of the black unions that organized many strikes. In 1976, a demonstration in Soweto against the mandatory use of Afrikaans in schools resulted in a massacre: more than 1,000 deaths.

Hector Pieterson Memorial, in honour of a 13 year old boy who died during 'Sharpeville', South AfricaPhoto: Ina96 CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Hector Pieterson Memorial, in honour of a 13 year old boy who died during 'Sharpeville', South AfricaPhoto: Ina96 CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

At the funeral of Steve Biko things started to get messy again. Biko died on September 12, 1977 of injuries sustained in a police cell.

The international community issued an arms boycott on this. In 1978 Prime Minister Vorster stepped down and Pieter Willem Botha took over the leadership of the reigning Nasionale Party. He soon envisioned that white South Africa would not have a long future and gave the Asians and colored people their own room in parliament. He also tried by the formation of a black middle class to create a dam against the ANC, which gained more and more support among the black population. The governments of the black homelands, including those of Kwa Zulu (where G. Buthelezi had long enjoyed popularity with his Inkatha movement), were also called in for that purpose.

Steve Biko, fighter against Apartheid in South AfricaPhoto: Unknown photographer CC 4.0 International no changes made

Steve Biko, fighter against Apartheid in South AfricaPhoto: Unknown photographer CC 4.0 International no changes made

This hardly changed the bad position of these groups, not to mention the black part of the population. They only had something to say in the homelands not officially recognized by anyone. However, these prudent reforms did have consequences. For example, the Conservative Party led by Andries Treurnicht split from the Nasionale Party. In addition, more than 600 South African organizations united in the United Democratic Front (UDF) to engage in the fight against the apartheid regime.

Foreign countries began to stir and various (including economic) sanctions against the apartheid regime followed. The neighboring countries in Southern Africa, the "frontline states", also condemned apartheid policies and tried to hit South Africa economically by trying to become less dependent on South Africa. In the 1980s, foreign pressures continued to intensify and apartheid was gradually dismantled. But first, in the mid-1980s, the freedom measures were tightened to prevent disturbances. This led to a popular uprising organized by the ANC-in-exile, which was violently repressed. Botha then declared a state of emergency and at that time South Africa had in fact become a police state, giving the army, police and intelligence services free rein.

International protest and Nelson Mandela is released

The international community responded by increasingly isolating South Africa. The unions united in the COSATU also put increasing pressure on the Botha government and also demanded the release of Nelson Mandela, the symbol of the fight against apartheid.

The ban on peaceful opposition to apartheid, promulgated in 1988, sparked a storm of international protests. In Natal, meanwhile, the struggle between the rival black groups ANC (mainly Xhosa) and the Inkatha movement of Buthelezi (mainly Zulu) flared up again.

In early 1989, Botha retired as Prime Minister and later as President for health reasons, and with the arrival of the new husband of the Nasionale Party, Frederik Willem de Klerk, the reform process accelerated irreversibly. De Klerk understood that it couldn't go on like this and decided in 1990 to release Nelson Mandela. Furthermore, he abolished most apartheid laws and all opposition parties (including ANC and PAC) were legalized. Namibia's independence was negotiated during the 1980s, which finally led to its declaration of independence on 21 March 1990. South African troops withdrew from Namibia. The Walvis Bay issue was raised in Sept. Solved in 1993 when South Africa agreed to transfer the area to Namibia on 1 March 1994.

Frederik Willem de Klerk released Nelson Mandela from prison South AfricaPhoto: Mark Neyman / Government Press Office (Israel) CC 3.0 no changes made

Frederik Willem de Klerk released Nelson Mandela from prison South AfricaPhoto: Mark Neyman / Government Press Office (Israel) CC 3.0 no changes made

The last apartheid law, the Law on Personal Registration, was abolished in 1991. In September 1991, De Klerk, Mandela and Buthelezi, together with 23 other organizations, signed a national peace agreement, in which the parties undertook, among other things, to limit the violence. Nevertheless, the violent rivalry between ANC members in particular and the Zulu of Inkatha leader Buthelezi did not subside. Especially in Natal and in the urban areas in Transvaal (including Soweto) many victims were reported.

On March 17, 1992, Nelson Mandela was finally released and negotiations for a new constitution and a new government could begin (CODESA = Convention for a Democratic South Africa). A 1992 referendum found that most whites supported the reforms, but leaders De Klerk (NP), Nelson Mandela (ANC) and Buthelezi (Inkatha Freedom Party of the Zulus) were unable to reach any agreement. For example, ANC and IFP already had serious views on the governance of the Zulu community in Natal. This led to very violent clashes between supporters of both parties in Natal and the townships around Johannesburg. Thousands of blacks died and all parties were powerless. In April 1992, the EC lifted the oil boycott (effective from 1985), as well as the sports boycott and the ban on scientific and cultural contacts with South Africa. De Klerk and Mandela's efforts to establish a black majority government acceptable to the white population led in 1993 to the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to both.

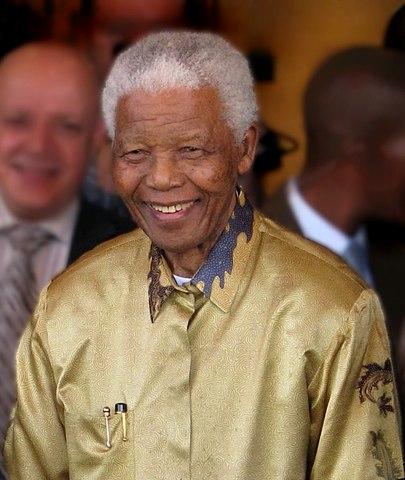

Nelson Mandela, first black president of South AfricaPhoto: South Africa The Good News/www.sagoodnews.co.za CC 2.0 no changes made

Nelson Mandela, first black president of South AfricaPhoto: South Africa The Good News/www.sagoodnews.co.za CC 2.0 no changes made

First democratic elections

In 1993, it was agreed that a provisional parliament and a government of national unity would govern the country until 1999. Despite protests and violence by white extremists, the first democratic elections were held in South Africa from 26 to 29 April 1994. Nelson Mandela became the big winner and the ANC the biggest party with 62% of the votes. The NP (20%) and the IFP (10%) only gained a majority in the Western Cape and Kwazulu Natal respectively. Nelson Mandela became president, with De Klerk (NP) and Thabo Mbeki (ANC) as vice-presidents. Mandela's program included the construction of a million homes in five years and improvements in education and health care. The international world immediately recognized the new country's administration and formally ended sanctions against South Africa. The country joined large international organizations such as the United Nations (June 1994), OAE and OMF.

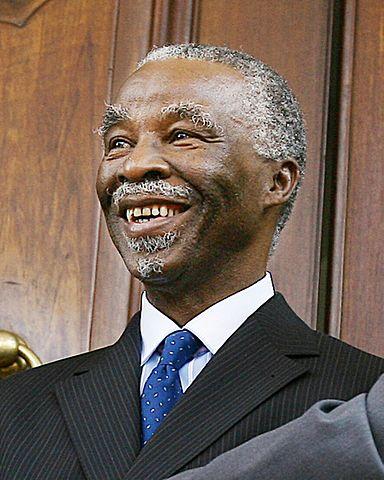

Nelson Mandela stepped down as agreed and handed over the lead to Thabo Mbeki. The human rights situation during the apartheid regime was investigated by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

Thabo Mbeki, from 1999-2008 president of South AfricaPhoto: Ricardo Stuckert CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

Thabo Mbeki, from 1999-2008 president of South AfricaPhoto: Ricardo Stuckert CC 3.0 Unported no changes made

President Mandela, who announced in 1995 that he was not eligible for re-election after his term in office in 1999, soon faced several crises. Pastor Allen Boesak, an important figure within the ANC, for example, withdrew as candidate ambassador for South Africa to the UN after accusations that he had put aid funds for social projects in his own pocket.

Furthermore, Winnie Mandela, from whom President Mandela lived separately, was discredited by a series of statements distancing herself from government policy and financial scandals. She has also been charged with involvement in a number of murders. In May 1995, Mandela accused Inkatha of fueling violence in KwaZulu / Natal province, killing more than 2,000. Local elections in November 1995 won two-thirds of the votes cast for the ANC.

In May 1996, the Constitutional Assembly overwhelmingly approved the new Constitution, which will enter into force after the 1999 elections. In May 1996, the Nasional Party left the Government of National Unity and continued in opposition under the name of New National Party. A month earlier, Bishop Tutu opened the first session of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was set up to clarify the crimes of apartheid. Perpetrators of the "dirty war" would receive amnesty if they gave the Commission a full opening.

Flag Nuwe Nasionale Party (new National Party)Photo: Vectorebus (public domain)

Flag Nuwe Nasionale Party (new National Party)Photo: Vectorebus (public domain)

The government pursued a prudent economic policy aimed at reducing the budget deficit and reducing taxes for low and middle incomes. GDP grew by over 4% and inflation fell to over 7%. Army units were deployed in the Johannesburg area to fight crime. The insecurity was a major reason for the hesitant attitude of international investors.

21st century

On April 14, 2004, national elections were held for the third time since the end of apartheid. President Mbeki was reelected. Voter turnout was around 75%, indicating a continued high level of political engagement, albeit still targeting "identity politics". The ANC obtained more than two thirds (almost 70%) of the votes cast, which means it is now in a position to make unilateral constitutional changes. However, the first indications indicate that the ANC will not use this option, but rather seeks consensus. President Mbeki has therefore included a number of non-ANC members into his government squad, notably members of The New National Party (NNP) that emerged from the old "apartheid" National Party.

Both the NNP and IFP lost votes and seats in the election, making the ANC the largest party in all nine provinces and (with the exception of Kwazulu Natal) an absolute majority in all provinces. In August 2004, NNP leader Van Schalkwyk announced that the NNP would merge with the ANC. This is a remarkable step, as a result of which the founders of apartheid are now absorbed by the party that has fiercely contested that system.

The land reform issue, consisting of land restitution, land redistribution and ownership review, is also an important part of the transformation process in South Africa. Based on a system of willing buyer, willing seller, land is purchased for restitution or redistribution among former disadvantaged population groups. However, the process is too slow for many of them. More vigorous measures were announced during the November 2005 Land Summit, with the aim of reducing the need for expropriation, for example.

The growing contradictions within the alliance came even more sharply into the limelight around the local elections of March 1, 2006, with the ANC incidentally maintaining the absolute majority in most districts against most expectations. Only in Cape Town did the ANC surrender power to the Democratic Alliance.

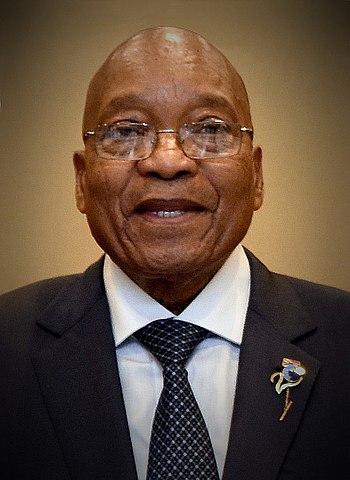

Jacob Zuma, between 2007 and 2017 leader of the ANCPhoto: Australian Embassy Jakarta CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Jacob Zuma, between 2007 and 2017 leader of the ANCPhoto: Australian Embassy Jakarta CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Another fact that has sharpened the political relations in South Africa (and especially within the ANC) is the events surrounding ex-vice president Jacob Zuma. Zuma is suspected of fraud and corruption in a major arms deal involving prominent ANC businessman Schabir Shaik. Shaik has since been convicted and the judge ruled that his relationship with Zuma was “generally corrupt”. The case against Zuma starts in June 2006. Zuma was put aside by President Mbeki because of this matter and pending the lawsuit and replaced by Mrs. Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka. In addition, in November 2005, Zuma was charged with the rape suit of a 31-year-old family friend and HIV-positive AIDS activist. Pending this matter, Zuma also had to resign its leadership activities within the ANC. Zuma, and large parts of the ANC believe that both cases are part of a plot against him to keep him from running for president in 2009 when Mbeki's term ends. Zuma has now been acquitted of the rape charge and has resumed his duties within the ANC. While both issues have weakened Zuma's position, his role has certainly not yet been played. Within the ANC and between the Alliance partners, this has led to a fierce battle over the succession of President Mbeki. In December 2007 Zuma becomes President of the ANC, which strengthens his position as a presidential candidate. In May 2008, ethnic violence emerged against immigrants from Malawi Zimbabwe and Mozambique. In September 2008, Mbeki stepped down under pressure from the ANC and Kgalema Motlanthe is elected interim president until the 2009 presidential election, where Zuma is the main contender. Zuma is elected president in May 2009. South Africa will host the World Cup in June 2010. In May 2011, the opposition of the Democratic Alliance doubles its vote in local elections. In 2012 it is restless within the ANC. The police shoot demonstrators (there are many deaths) at the Marikana mine and Julius Malema, former youth leader at the ANC, is accused by Zuma of fraud. According to Malema, these allegations are politically motivated because of his criticism of his actions against the strikers. In December, Zuma is reelected as leader of the ANC.

After a long illness, Nelson Mandela died on December 5, 2013 at the age of 95. The funeral takes place under the overwhelming interest of world leaders. In May 2014, the ruling ANC wins elections despite corruption allegations from its leader President Zuma. In February 2015, Zuma launched plans to reduce farm size and discourage foreign ownership. Allegations of bribery surrounding the 2010 FIFA World Cup and admitting of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir despite an international arrest warrant will come in June 2015. In March 2016, the Supreme Court found that Zuma had violated the constitution for failing to repay public money used to improve his private home. In December 2017, Zuma loses the fight for the ANC party chairmanship from his critic Cyril Ramaphosa and further weakens his post. In January 2018, the ANC board insists on the resignation of Zuma. There are fears that the party will perform poorly in the 2019 parliamentary elections when the unpopular Zuma stays on.

Cyril Ramaphosa, president of South AfricaPhoto: ITU Pictures CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

Cyril Ramaphosa, president of South AfricaPhoto: ITU Pictures CC 2.0 Generic no changes made

On February 14, 2018, Zuma stepped down as president of South Africa and a day later Cyril Ramaphosa was sworn in as the new president. The elections of May 8, 2019 were won by a large majority by the ANC (57.51% of the votes) and Ramaphosa was sworn in as president for five years on May 25, 2019. Next elections are planned in 2024.

Sources

Dekker, M. / Zuid-Afrika

Gottmer/Becht

Luirink, B. / Zuid-Afrika : mensen, politiek, economie, cultuur, milieu

Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen,

Moerkamp, J. / Zuid-Afrika

ANWB

Schaap, D. / Zuid-Afrika

Minbuza Kosmos-Z&K

Zuid-Afrika

Cambium

CIA - World Factbook

BBC - Country Profiles

Last updated February 2026Copyright: Team The World of Info